ご利用について

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of rare cancers of childhood. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians who care for cancer patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

CONTENTS

- General Information About Rare Cancers of Childhood

-

Introduction

Cancer in children and adolescents is rare, although the overall incidence of childhood cancer has been slowly increasing since 1975.[ 1 ] Referral to medical centers with multidisciplinary teams of cancer specialists experienced in treating cancers that occur in childhood and adolescence should be considered for children and adolescents with cancer. This multidisciplinary team approach incorporates the skills of the primary care physician, pediatric surgeons, radiation oncologists, pediatric medical oncologists/hematologists, rehabilitation specialists, pediatric nurse specialists, social workers, and others to ensure that children receive treatment, supportive care, and rehabilitation that will achieve optimal survival and quality of life. (Refer to the PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care summaries for specific information about supportive care for children and adolescents with cancer.)

Guidelines for pediatric cancer centers and their role in the treatment of pediatric patients with cancer have been outlined by the American Academy of Pediatrics.[ 2 ] At these pediatric cancer centers, clinical trials are available for most types of cancer that occur in children and adolescents, and the opportunity to participate in these trials is offered to most patients and their families. Clinical trials for children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer are generally designed to compare potentially better therapy with therapy that is currently accepted as standard. Most of the progress made in identifying curative therapy for childhood cancers has been achieved through clinical trials. Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Dramatic improvements in survival have been achieved for children and adolescents with cancer. Between 1975 and 2010, childhood cancer mortality decreased by more than 50%.[ 3 ] Childhood and adolescent cancer survivors require close monitoring because cancer therapy side effects may persist or develop months or years after treatment. (Refer to the PDQ summary on Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer for specific information about the incidence, type, and monitoring of late effects in childhood and adolescent cancer survivors.)

Childhood cancer is a rare disease, with about 15,000 cases diagnosed annually in the United States in individuals younger than 20 years.[ 4 ] The U.S. Rare Diseases Act of 2002 defines a rare disease as one that affects populations smaller than 200,000 persons. Therefore, all pediatric cancers are considered rare.

The designation of a rare tumor is not uniform among pediatric and adult groups. Adult rare cancers are defined as those with an annual incidence of fewer than six cases per 100,000 people, and are estimated to account for up to 24% of all cancers diagnosed in the European Union and about 20% of all cancers diagnosed in the United States.[ 5 ][ 6 ] Also, the designation of a pediatric rare tumor is not uniform among international groups, as follows:

These rare cancers are extremely challenging to study because of the low incidence of patients with any individual diagnosis, the predominance of rare cancers in the adolescent population, and the lack of clinical trials for adolescents with rare cancers such as melanoma.

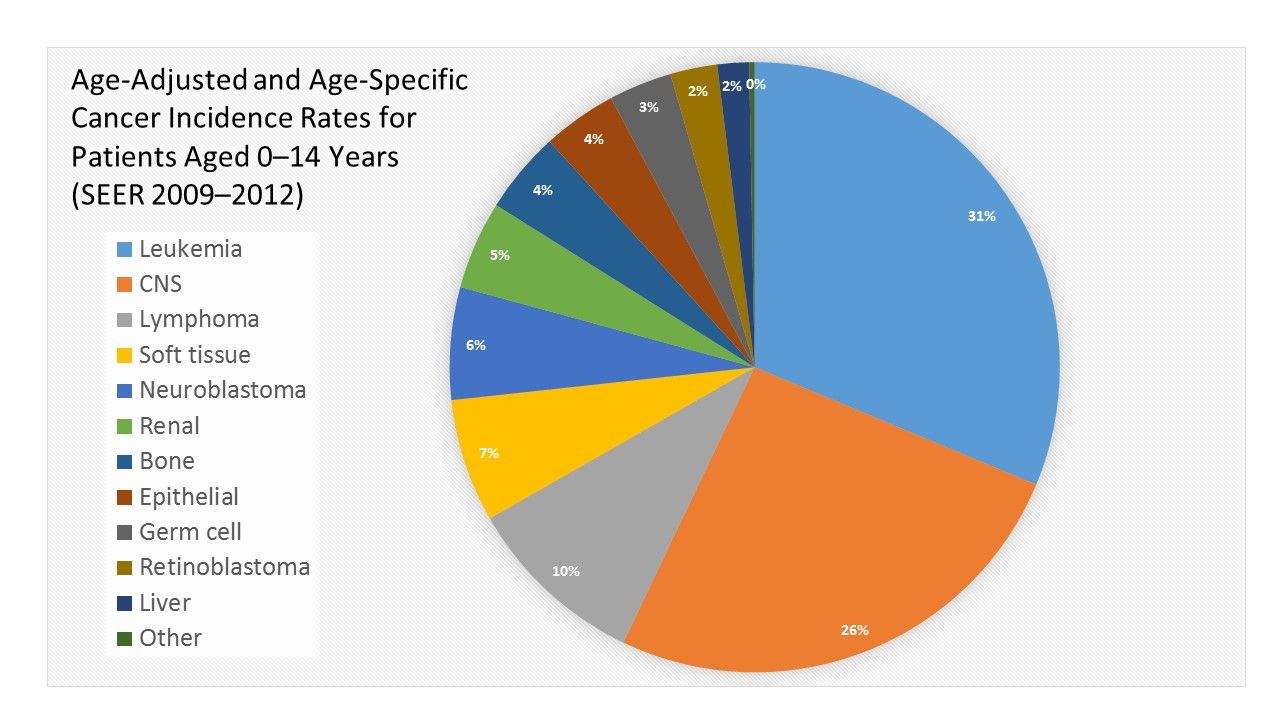

Figure 1. Age-adjusted and age-specific (0–14 years) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer incidence rates from 2009 to 2012 by International Classification of Childhood Cancer group and subgroup and age at diagnosis, including myelodysplastic syndrome and group III benign brain/central nervous system tumors for all races, males, and females.

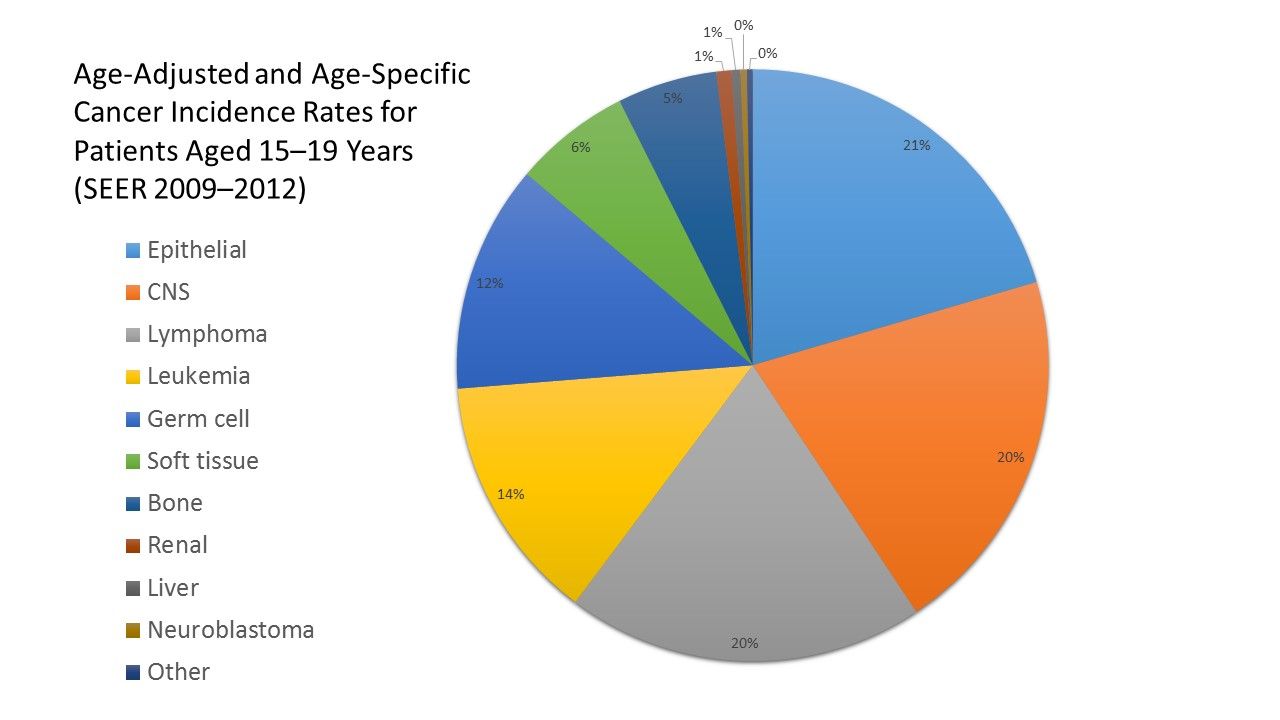

Figure 2. Age-adjusted and age-specific (15–19 years) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer incidence rates from 2009 to 2012 by International Classification of Childhood Cancer group and subgroup and age at diagnosis, including myelodysplastic syndrome and group III benign brain/central nervous system tumors for all races, males, and females. Some investigators have used large databases, such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) and the National Cancer Database, to gain more insight into these rare childhood cancers. However, these database studies are limited. Several initiatives to study rare pediatric cancers have been developed by the COG and other international groups, including the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (Société Internationale D'Oncologie Pédiatrique [SIOP]). The Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Onkologie und Hämatologie (GPOH) rare tumor project was founded in Germany in 2006.[ 10 ] The TREP was launched in 2000,[ 7 ] and the Polish Pediatric Rare Tumor Study Group was launched in 2002.[ 11 ] In Europe, the rare tumor studies groups from France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and the United Kingdom have joined in the European Cooperative study Group on Pediatric Rare Tumors (EXPeRT), focusing on international collaboration and analyses of specific rare tumor entities.[ 12 ] Within the COG, efforts have concentrated on increasing accrual to COG registries (Project Every Child) and tumor banking protocols, developing single-arm clinical trials, and increasing cooperation with adult cooperative group trials.[ 13 ] The accomplishments and challenges of this initiative have been described in detail.[ 8 ][ 14 ]

The tumors listed in this summary are very diverse; they are arranged in descending anatomic order, from infrequent tumors of the head and neck to rare tumors of the urogenital tract and skin. All of these cancers are rare enough that most pediatric hospitals might see less than a handful of some histologies in several years. The majority of the histologies listed here occur more frequently in adults. Information about these tumors may also be found in sources relevant to adults with cancer.

The Rare Cancers of Childhood Treatment summary has been separated into individual summaries for each topic. Please use the lists below or the following link to find the individual summaries: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/pdq/information-summaries/pediatric-treatment.

参考文献- Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, et al.: Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol 28 (15): 2625-34, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Corrigan JJ, Feig SA; American Academy of Pediatrics: Guidelines for pediatric cancer centers. Pediatrics 113 (6): 1833-5, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, et al.: Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer 120 (16): 2497-506, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, et al.: Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64 (2): 83-103, 2014 Mar-Apr.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Botta L, et al.: Burden and centralised treatment in Europe of rare tumours: results of RARECAREnet-a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 18 (8): 1022-1039, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- DeSantis CE, Kramer JL, Jemal A: The burden of rare cancers in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 67 (4): 261-272, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ferrari A, Bisogno G, De Salvo GL, et al.: The challenge of very rare tumours in childhood: the Italian TREP project. Eur J Cancer 43 (4): 654-9, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pappo AS, Krailo M, Chen Z, et al.: Infrequent tumor initiative of the Children's Oncology Group: initial lessons learned and their impact on future plans. J Clin Oncol 28 (33): 5011-6, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., eds.: SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012. National Cancer Institute, 2015. Also available online. Last accessed June 22, 2021.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Brecht IB, Graf N, Schweinitz D, et al.: Networking for children and adolescents with very rare tumors: foundation of the GPOH Pediatric Rare Tumor Group. Klin Padiatr 221 (3): 181-5, 2009 May-Jun.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Balcerska A, Godziński J, Bień E, et al.: [Rare tumours--are they really rare in the Polish children population?]. Przegl Lek 61 (Suppl 2): 57-61, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bisogno G, Ferrari A, Bien E, et al.: Rare cancers in children - The EXPeRT Initiative: a report from the European Cooperative Study Group on Pediatric Rare Tumors. Klin Padiatr 224 (6): 416-20, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Musselman JR, Spector LG, Krailo MD, et al.: The Children's Oncology Group Childhood Cancer Research Network (CCRN): case catchment in the United States. Cancer 120 (19): 3007-15, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pappo AS, Furman WL, Schultz KA, et al.: Rare Tumors in Children: Progress Through Collaboration. J Clin Oncol 33 (27): 3047-54, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Head and Neck Cancers

-

It must be emphasized that these cancers are seen very infrequently in patients younger than 15 years, and most of the evidence is derived from small case series or cohorts combining pediatric and adult patients.

Childhood sarcomas often occur in the head and neck area and they are described in other sections. Rare pediatric head and neck cancers include the following:

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Nasopharyngeal Cancer Treatment for more information.

Esthesioneuroblastoma

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Esthesioneuroblastoma Treatment for more information.

Thyroid Tumors

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Thyroid Cancer Treatment for more information.

Oral Cavity Cancer

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Oral Cavity Cancer Treatment for more information.

Salivary Gland Tumors

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Salivary Gland Tumors Treatment for more information.

Laryngeal Cancer and Papillomatosis

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Laryngeal Tumors Treatment for more information.

Midline Tract Carcinoma Involving the NUT Gene (NUT Midline Carcinoma)

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Midline Tract Carcinoma Involving the NUT Gene (NUT Midline Carcinoma) Treatment for more information.

- Thoracic Cancers

-

The prognosis, diagnosis, classification, and treatment of these thoracic cancers are discussed below. It must be emphasized that these cancers are seen very infrequently in patients younger than 15 years, and most of the evidence is derived from case series.[ 1 ]

Rare pediatric thoracic cancers include the following:

Breast Cancer

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Breast Cancer Treatment for more information.

Lung Cancer

Most pulmonary malignant neoplasms in children are due to metastatic disease, with an approximate ratio of primary malignant tumors to metastatic disease of 1:5.[ 2 ]

The following are the most common malignant primary tumors of the lung:

Tracheobronchial Tumors

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Tracheobronchial Tumors Treatment for more information.

Pleuropulmonary Blastoma

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Pleuropulmonary Blastoma Treatment for more information.

Esophageal Cancer

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Esophageal Cancer Treatment for more information.

Thymoma and Thymic Carcinoma

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Thymoma and Thymic Carcinoma Treatment for more information.

Cardiac (Heart) Tumors

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Cardiac (Heart) Tumors Treatment for more information.

参考文献- Yu DC, Grabowski MJ, Kozakewich HP, et al.: Primary lung tumors in children and adolescents: a 90-year experience. J Pediatr Surg 45 (6): 1090-5, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Weldon CB, Shamberger RC: Pediatric pulmonary tumors: primary and metastatic. Semin Pediatr Surg 17 (1): 17-29, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Abdominal Cancers

-

The prognosis, diagnosis, classification, and treatment of these abdominal cancers are discussed below. It must be emphasized that these cancers are seen very infrequently in patients younger than 15 years, and most of the evidence is derived from case series. (Refer to the PDQ summary on Wilms Tumor and Other Childhood Kidney Tumors for information about kidney tumors.)

Rare pediatric abdominal cancers include the following:

Adrenocortical Carcinoma

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Adrenocortical Carcinoma Treatment for more information.

Gastric (Stomach) Cancer

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Stomach (Gastric) Cancer Treatment for more information.

Pancreatic Cancer

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Pancreatic Cancer Treatment for more information.

Colorectal Cancer

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Colorectal Cancer Treatment for more information.

Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumors

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumors Treatment for more information.

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST)

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors Treatment for more information.

- Genital/Urinary Tumors

-

The prognosis, diagnosis, classification, and treatment of these genital/urinary tumors are discussed below. It must be emphasized that these tumors are seen very infrequently in patients younger than 15 years, and most of the evidence is derived from case series.

Rare pediatric genital/urinary tumors include the following:

Bladder Cancer

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Bladder Cancer Treatment for more information.

Testicular Cancer (Non–Germ Cell)

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Testicular Cancer Treatment for more information.

Ovarian Cancer (Non–Germ Cell)

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Ovarian Cancer Treatment for more information.

Cervical and Vaginal Cancer

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Cervical and Vaginal Cancer Treatment for more information.

- Other Rare Childhood Cancers

-

The prognosis, diagnosis, classification, and treatment of these other rare childhood cancers are discussed below. It must be emphasized that these cancers are seen very infrequently in patients younger than 15 years, and most of the evidence is derived from case series.

Other rare childhood cancers include the following:

Mesothelioma

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Mesothelioma Treatment for more information.

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia (MEN) Syndromes and Carney Complex

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia (MEN) Syndromes Treatment for more information.

Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma Treatment for more information.

Skin Cancer (Melanoma, Basal Cell Carcinoma [BCC], and Squamous Cell Carcinoma [SCC])

(Refer to the PDQ summary on Genetics of Skin Cancer for more information about specific gene mutations and related cancer syndromes and the Intraocular [Uveal] Melanoma section of this summary for information about uveal melanoma in children.)

Melanoma

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Melanoma Treatment for more information.

BCC and SCC

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Basal Cell Carcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Skin Treatment for more information.

Intraocular (Uveal) Melanoma

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Intraocular (Uveal) Melanoma Treatment for more information.

Chordoma

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Chordoma Treatment for more information.

Carcinoma of Unknown Primary Site

Refer to the PDQ summary on Childhood Carcinoma of Unknown Primary Treatment for more information.

- Changes to This Summary (02/10/2021)

-

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Other Rare Childhood Cancers

Added Mesothelioma as a new subsection.

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® - NCI's Comprehensive Cancer Database pages.

- About This PDQ Summary

-

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of rare cancers of childhood. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians who care for cancer patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Rare Cancers of Childhood Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/hp/rare-childhood-cancers-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389315]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either “standard” or “under clinical evaluation.” These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s Email Us.

画像を拡大する

画像を拡大する