ご利用について

医療専門家向けの本PDQがん情報要約では、小児がんの治療における同種造血幹細胞移植の利用について、専門家の査読を経た、証拠に基づく情報を包括的に提供している。本要約は、患者を治療する臨床家に情報を与え支援するための情報資源として作成されている。医療上の意思決定のための正式なガイドラインや推奨事項を提供するものではない。

本要約は編集作業において米国国立がん研究所(NCI)とは独立したPDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Boardにより定期的にレビューされ、随時更新される。本要約は独自の文献レビューの結果を反映するものであり、NCIまたは米国国立衛生研究所(NIH)の方針声明を示すものではない。

CONTENTS

- 同種造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)後の治療成績の改善

-

過去20年間で、大幅な進歩により同種造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)後の治療成績は改善している。[ 1 ][ 2 ][ 3 ]生存期間で見た最も有意な改善は非血縁および代替ドナーによる移植でみられた。[ 4 ][ 5 ][ 6 ]こうした生存期間の改善について考えられる理由としては、患者選択の改善、支持療法の改善、治療レジメンの洗練化、幹細胞ソースに応じたアプローチの改善、HLAタイピングの向上などがある。以下のセクションでは、HLAタイピングの最適化や幹細胞ソースの選択など、HSCTの修正可能な側面に焦点を置く。

参考文献- Hahn T, McCarthy PL, Hassebroek A, et al.: Significant improvement in survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation during a period of significantly increased use, older recipient age, and use of unrelated donors. J Clin Oncol 31 (19): 2437-49, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Horan JT, Logan BR, Agovi-Johnson MA, et al.: Reducing the risk for transplantation-related mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: how much progress has been made? J Clin Oncol 29 (7): 805-13, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wood WA, Lee SJ, Brazauskas R, et al.: Survival improvements in adolescents and young adults after myeloablative allogeneic transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 20 (6): 829-36, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- MacMillan ML, Davies SM, Nelson GO, et al.: Twenty years of unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation for pediatric acute leukemia facilitated by the National Marrow Donor Program. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 14 (9 Suppl): 16-22, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Harvey J, Green A, Cornish J, et al.: Improved survival in matched unrelated donor transplant for childhood ALL since the introduction of high-resolution matching at HLA class I and II. Bone Marrow Transplant 47 (10): 1294-300, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Majhail NS, Chitphakdithai P, Logan B, et al.: Significant improvement in survival after unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation in the recent era. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (1): 142-50, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 造血器腫瘍に対する同種造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)の適応

-

HSCTの適応は、対象とする悪性腫瘍のリスク分類が変化したり、一次治療の有効性が改善したりするのにつれて、時間とともに変化していく。対象疾患に対する完全な治療という観点で具体的な適応を検討するのが最善である。このことを念頭に置きつつ、小児における同種HSCTの最も一般的な適応をカバーする具体的な要約を示したセクションへのリンクを以下に提示する。

- 急性リンパ芽球性白血病(ALL)

- 急性骨髄性白血病(AML)

- 骨髄異形成腫瘍(MDS)

- 若年性骨髄単球性白血病(JMML)

- 慢性骨髄性白血病(CML)

- HLAマッチングと造血幹細胞ソース

-

HLAの概要

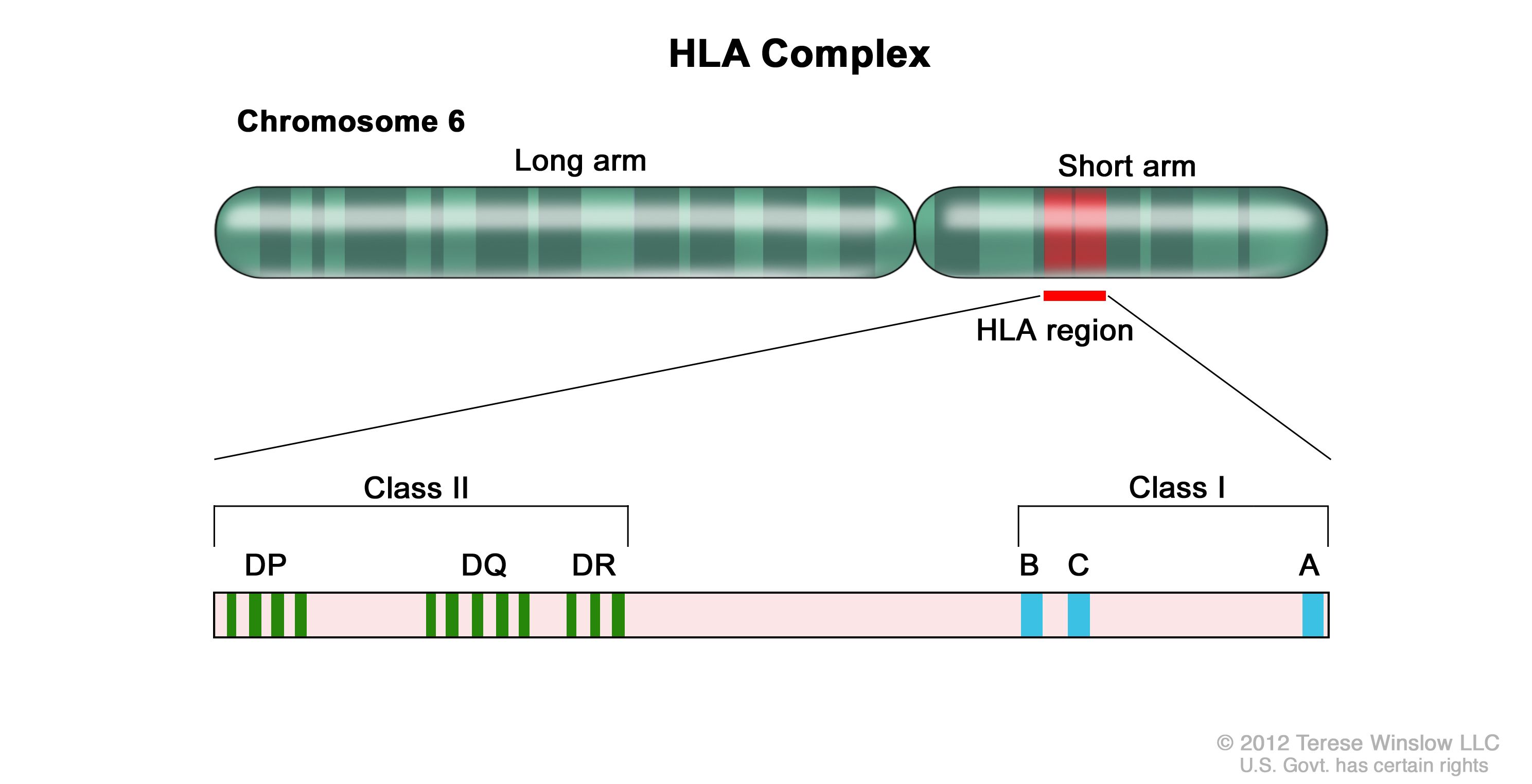

同種造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)の成功には、6番染色体に位置する主要組織適合性複合体についてドナーとレシピエントのHLAが適切に一致していることが不可欠である(図1、表1、および表 2を参照)。

図1.HLA複合体。ヒト6番染色体とHLA領域の拡大図。グラスI B、C、AアレルとクラスII DP、DQ、DRアレルについて具体的なHLA遺伝子座の位置が示されている。 HLAクラスI(A、B、Cなど)およびクラスII(DRB1、DRB3、DRB4、DRB5、DQB1、DPB1など)アレルは高度の多型性を示す。したがって、適切に一致した非血縁ドナーを見つけることは、一部の患者、特に特定の人種集団(例、アフリカ系、ヒスパニック系、アジア系、太平洋諸島系)の患者にとって容易なことではない。[ 1 ][ 2 ]がん患者の完全同胞でHLAが一致している可能性は25%である。

HLA評価の初期の血清学的手法によってHLA抗原の数が定義されたが、DNAベースのより正確な方法論により、血清学的に判定されるHLA抗原一致の最大40%がアレルレベルではHLA不一致であることが示されている。アレルレベルで不一致のドナーを選択すると、抗原レベルで不一致の場合に近い程度まで生存率と移植片対宿主病(GVHD)の発生率に影響が及ぶため、このレベルの差異は臨床的に重要である。[ 3 ]このため、非血縁ドナーを選択する場合は、DNAベースのアレルレベルでのHLAタイピングが標準となっている。

National Marrow Donor ProgramからHLAマッチングのガイドラインが公表されている。同ガイドラインではアレルレベルのマッチングに関する用語として、抗原認識ドメイン(antigen recognition domain)が採用されているが、これは、特定のHLA型を定義するために用いるアレルレベルの類似性が抗原認識に直接用いられる領域と関連しているという事実を参考にしている。それらの領域以外でのHLA蛋白の多型は、これらの分子の機能に関与しない。したがって、HLA検査では評価対象とされないことが多く、HLA不一致の一因となる可能性は低い。[ 4 ]

表1.それぞれの造血幹細胞ソースに現在用いられているHLAタイピングのレベルa,b,c クラスI抗原 クラスII抗原 PBSC = 末梢血幹細胞。 aHLA抗原:HLA蛋白を低い精度で識別する血清学的に定義された方法。アレルレベルでのタイピングとは少なくとも40%の頻度で一致しない。最初の2つの数字で指定される(すなわち、HLA B 35:01の場合、抗原はHLA B 35である)。 bHLAアレル:塩基配列決定法や固有の差異を検出する他のDNAベースの方法で遺伝子配列を決定することにより、固有のHLA蛋白を高い精度で識別する方法。少なくとも4つの数字で指定される(すなわち、HLA B 35:01の場合、35が抗原、01がアレルを表す)。 c不一致ドナーの拡大クラスIIタイピングを含めたHLAタイピングに関するコンセンサスに基づく推奨が、National Cancer Institute/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Instituteが後援するBlood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Networkから公表されている。[ 5 ] d同胞の場合は、ハプロタイプが完全に一致し、A~DRB1領域に交差がないことを確認する必要がある。親のタイピングを行って、ハプロタイプが確認されれば、クラスIの抗原レベルのタイピングで十分である。親のハプロタイプが得られていない場合は、8アレルのアレルレベルタイピングが推奨される。 e親、いとこ、その他の家系員で、表現型が一致しているか、HLAがほぼ完全に一致している。 幹細胞ソース HLA A HLA B HLA C HLA DRB1 一致同胞dの骨髄/PBSC 抗原またはアレル 抗原またはアレル 任意 アレル 不一致同胞/その他の血縁ドナーeの骨髄/PBSC アレル アレル アレル アレル 非血縁ドナーの骨髄/PBSC アレル アレル アレル アレル 非血縁ドナーの臍帯血 抗原(アレル推奨) 抗原(アレル推奨) アレル推奨 アレル 表2.HLA抗原およびアレルの一致を記述するための数字の定義 下記のHLA抗原およびアレルが一致している場合: 医師はその一致タイプを以下のように考える: A、B、およびDRB1 6/6 A、B、C、およびDRB1 8/8 A、B、C、DRB1、およびDQB1 10/10 A、B、C、DRB1、DQB1、およびDPB1 12/12 同胞および血縁ドナーに対するHLAマッチングの考慮事項

最もよく選択される血縁ドナーは、両親を同じくする同胞のうち、最低でも抗原レベルでHLA A、HLA B、およびHLA DRB1についてHLAが一致する個人である。6番染色体上でHLA AとHLA DRB1は離れているため、ドナー候補の同胞との一致において交差による不一致がみられる可能性は約1%である。交差にはHLA C抗原が関係する可能性があることから、また、両親と共有しているHLA抗原が実際にはアレルレベルで異なっている可能性があることから、多くの施設では、ドナー候補である同胞に対して、重要なHLA抗原すべて(HLA A、HLA B、HLA C、およびDRB1)についてアレルレベルでのHLAタイピングを行っている。半同胞の血縁ドナーでは、異なる親に由来する類似したハプロタイプもアレルレベルでは異なっている可能性があるため、完全なHLAタイピングを行うべきである。

一部の研究では1抗原不一致の血縁ドナー(5/6抗原一致)が一致同胞ドナーと区別なく採用されていたが、小児HSCTレシピエントを対象とした大規模研究であるCenter for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research(CIBMTR)研究により、5/6抗原一致血縁ドナーを採用した場合のGVHD発生率および全生存(OS)率は8/8アレル一致非血縁ドナーと同等で、完全一致同胞ドナーと比較してもわずかに生存率が劣るのみであったことが示された。[ 6 ]単一の不一致がある同胞がいる場合は、その不一致が交差により生じたものであれば、それが1つの抗原のみで生じたことを確認するために、対象を拡大したタイピングを行うべきである。複数抗原不一致の同胞をドナーに選択する場合は、ハプロタイプ一致のアプローチが妥当となる可能性がある。

非血縁ドナーに対するHLAマッチングの考慮事項

非血縁同種骨髄移植では、ドナーとレシピエントの間でHLA A、HLA B、HLA C、およびDRB1抗原のペアがアレルレベルで一致している場合(8/8一致と呼ばれる)に至適な治療成績が達成される(表2を参照のこと)。[ 7 ]これらの抗原のいずれかに単一抗原/アレルの不一致がある場合(7/8一致)、生存の確率が5%~10%低下し、有意な(グレードIII~IVの)急性GVHDが同程度に増加する。[ 7 ]これら4つの抗原ペアのうち、HLA A、HLA C、およびDRB1に不一致があると、他の抗原の場合より死亡率の上昇幅が大きくなる可能性があるということが複数の報告で示されているが[ 3 ][ 7 ][ 8 ]、治療成績の差は小さく、一貫していないことから、特定の型の抗原不一致を別の型の抗原不一致より優先して選択することで好ましい不一致を選び出すことができると結論するのは非常に困難である。治療成績の改善または悪化と関連を示す特定の抗原や抗原ペアを明らかにするための試みが、多くの研究グループによってなされている。例えば、特定のHLA C不一致(HLA-C*03:03/03:04)では一致の場合と同程度の治療成績が得られている。したがって、他の点では一致しているドナー/ペアの組合せでは、この不一致を選択することが望ましい。[ 9 ]

クラスII抗原であるDRB1の不一致はGVHDの発生率を高め、生存率を低下させることがよく知られている。[ 8 ]その後の研究から、一致度8/8未満の状況ではDQB1、DPB1、DRB3、DRB4、DRB5の複数の不一致が治療成績低下につながることも示されている。[ 10 ]DPB1不一致は詳細に研究されており、T細胞エピトープマッチングに基づいて許容できると許容できないに分類されている。DPB1の許容できない不一致を示す10/10一致の患者では移植関連死が多いが、生存率はDPB1一致または許容できる不一致の患者と同程度である。DPB1の許容できない不一致を示す9/10一致の患者は、許容できる不一致またはDPB1一致を示す患者よりも生存率が不良である。[ 11 ][ 12 ][ 13 ]

これらの知見を考慮に入れると、7/8または8/8一致の非血縁ドナーをルーチンに採用することができる。しかしながら、以下の対策により治療成績がさらに改善される可能性がある:

図2.ドナーまたはレシピエントにHLAアレルの重複があると、1つの半一致と1つの不一致となるが、不一致はGVHDを促進する方向(GVH-O)または拒絶反応を促進する方向(R-O)に働くことになる。 ドナーまたはレシピエントのHLAアレルの1つに重複があると、1つの半一致と1つの不一致となり、不一致は一方向に働く。図2は、それらの不一致がGVHDを促進する方向(GVH-O、ドナー細胞がGVHDを引き起こしうるレシピエントの不一致を検出できる状態)と拒絶反応を促進する方向(R-O、レシピエント細胞が拒絶反応を引き起こしうるドナーの不一致を検出できる状態)のいずれかの方向に起こることを示している。8/8一致の非血縁ドナーをGVH-O方向の不一致がある7/8一致ドナー、R-O方向の不一致がある7/8一致ドナー、または両方向の不一致がある7/8一致ドナーを比較すると、R-O方向の不一致では、グレードIIIおよびIVの急性GVHDの発生率が8/8一致と同程度になり、他の2つの組合せより良好である。R-O方向の不一致のみの7/8一致は、GVH-O方向および両方向の不一致よりも好ましい。[ 17 ]非血縁ドナーにおけるこの知見は、以下に概要を示す臍帯血移植レシピエントにおける知見と異なっている点に注意する必要がある。

非血縁臍帯血HSCTにおけるHLAマッチングおよび細胞数に関する考慮事項

非血縁臍帯血も一般的に用いられる造血幹細胞ソースの一つであり、臍帯血は分娩後すぐにドナー胎盤から採取される。臍帯血の処理とHLA型判定の後、凍結して臍帯血バンクに保存される。

非血縁臍帯血移植は、標準的な血縁または非血縁ドナーと比べてHLA一致の条件が厳密でなくても成功を収めているが、これはおそらく、子宮内で起きた抗原曝露が少なく、免疫学的な組成が異なるためと考えられる。臍帯血のマッチングは従来、HLA AおよびBについては中間レベルで、DRB1についてはアレルレベル(高精度)で行われている。しかしながら、以下で概説するように、より広範なタイピングが役に立つ可能性がある。

HLA一致度が6/6または5/6のユニットを用いた場合の方が治療成績は良好であるが[ 18 ]、HLA一致度が4/6以下のユニットを用いた場合でもHSCTの成功が認められている。大規模に実施されたCIBMTR/Eurocord研究では、8つの抗原に基づくアレルレベル(HLA A、HLA B、HLA C、およびDRB1でマッチング)の良好な一致が移植関連死亡率の低下と生存率の改善につながった。アレル一致度が4/8~7/8の場合と比べて8/8の場合で最良の治療成績が得られ、アレル不一致が5つ以上あった患者では生存率が不良であった。8/8一致の臍帯血移植を受けた患者では、良好な治療成績を達成するのに高用量の投与は必要なかった。しかしながら、1~3つのアレル不一致があった患者では総有核細胞数で3 × 107/kgを超える用量で移植関連死亡率の低下が認められ、4つのアレル不一致があった患者では移植関連死亡率を低下させるのに総有核細胞数で5 × 107/kgを超える用量が必要であった。[ 19 ]この結果は、7/8アレルを下回る不一致があると生存率が低下する良性疾患に対する臍帯血移植では、特に重要と指摘された。[ 20 ]多くの施設はこれら以外のアレルの型も判定して、可能な限り一致度の高いユニットを選択するであろうが、DQB1、DPB1、DRB3、DRB4、およびDRB5の不一致が及ぼす影響については詳細に研究されていない。

非血縁末梢血幹細胞(PBSC)または骨髄移植の場合と同様に、HLA感作がみられる患者では、拡張したHLA検査を行って適切な臍帯血ユニットの選択を支援することで、生着不成功の潜在的リスクを回避することができる。[ 21 ][ 22 ]また、不一致が遺伝によらない母親由来の抗原に関連したものである不一致臍帯血ユニットを選択することで、生存率が改善する可能性を示唆した証拠もある。[ 23 ][ 24 ]

非血縁ドナーの場合と同様に、ときにHLAアレルの重複がみられることもある(例、両染色体ともHLA Aアレルが01:01)。これがドナーの移植片に起きていて、そのアレルがレシピエントのアレルの1つと一致している場合、レシピエントの免疫系はドナーのアレルを一致とみなすが(拒絶反応の方向では一致)、ドナーの免疫系はレシピエントのアレルを不一致とみなす(GVHDの方向では不一致)。この部分的な不一致のバリエーションは臍帯血移植の治療成績に重要であることが示されている。GVHD方向のみ(すなわち、GVH-O)の不一致は、拒絶反応方向のみ(すなわち、R-O)の不一致と比べて、移植関連死亡率および全死亡率の低下につながる。[ 25 ]R-O不一致での治療成績は両方向不一致の場合と同程度である。[ 26 ]これらの研究結果から、臍帯血ドナーの選択基準としては一方向不一致の採用が有益である可能性が示唆されるが、Eurocord-European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantationの解析では、このタイプの不一致の価値について相反する結果が得られている。[ 27 ]

臍帯血HSCTには医療現場での適用範囲を広げている側面が2つある。第一に、複数のHLA不一致が認められる場合でも成功する可能性があるため、一致度4/6以上の臍帯血ユニットなら、さまざまな民族集団の95%以上の患者で発見することができる。[ 1 ][ 28 ]第二に、前述のように、十分な細胞数(最小量で総有核細胞数2.5~3 × 107/kgおよびCD34陽性細胞1.5 × 105/kg)には生存率改善との関連が認められている。[ 29 ][ 30 ]CD34陽性細胞数は測定法が標準化されていないため、臍帯血ユニットの判定には総有核細胞数が一般に用いられる。単一の臍帯血ユニットでは、大きいものでも体重40kg~50kgのレシピエントに対してこれらの最低限の細胞数しか提供することができないため、初期の臍帯血HSCTでは小柄な小児が主な対象とされた。その後の研究により、2つの臍帯血ユニットを用いることで、レシピエントに対する各ユニットのHLA一致度が4/6以上であれば、この量の問題を克服できることが示された。2単位の臍帯血なら投与できる細胞数が多くなるため、現在で大柄な小児や成人にも臍帯血移植が広く用いられている。[ 31 ]

単一の臍帯血ユニットで十分な細胞数を確保できる場合は、2つ目の臍帯血ユニットの追加は悪影響につながる可能性がある。[ 32 ][証拠レベルA1] 2つのランダム化試験により、十分量の単一の臍帯血ユニットを投与された小児に対して、2つ目の臍帯血ユニットを追加しても再発率、移植関連死亡率、および生存率は変化しなかったことが示され、広範な慢性GVHDの発生率上昇との関連が認められた。[ 32 ][ 33 ]

輸注前にサイトカインとその他の成分を併用して臍帯血の拡大培養をすることにより、臍帯血細胞の生着が標準アプローチの場合よりも早く起こる可能性があることが研究により示されている。[ 34 ][ 35 ][ 36 ][ 37 ]複数ユニットまたは分割ユニットを用いた検討では、拡大培養をしたユニットは生着は早いものの、その後の長期的な再構築では拡大培養をしないユニットの方が優れていることを示した研究もあるが[ 38 ]、増殖した細胞の長期的な維持が示され、拡大培養のプロセスを通して幹細胞が温存されることを示唆した研究もある。[ 36 ][ 37 ]これらのアプローチのいくつかが研究段階にある。米国食品医薬品局(FDA)は、1つのユニットを2つの画分に分けて、一方をニコチン酸アミドを添加した培地で拡大培養し、もう一方を無処理で輸注する方法(omidubicel)を承認した。あるランダム化試験では、omidubicelが標準的な臍帯血移植と比較された。Omidubicelを受けた患者では、HSCT後最初の3カ月間に好中球および血小板の生着が早く、細菌および真菌感染症が少なく、入院期間が短かった。[ 39 ]注目すべきことに、生存率とGVHDの転帰には差が認められなかった。

ハプロタイプ一致HSCT

HSCTの初期研究により、ドナー/レシピエント間のHLA不一致の数が多いほど、重度のGVHDを発症する患者の割合が累進的に高くなり、生存率が低下することが実証された。[ 40 ]他の研究から、たとえ非血縁ドナーの登録ドナー数が非常に多くなったとしても、まれなHLAハプロタイプの患者や特定の民族背景(例、アフリカ系、ヒスパニック系、アジア系、太平洋諸島系など)を有する患者は、望ましいレベルのHLA一致(アレルレベルでの7/8または8/8一致)を達成できる可能性は低いことが示された。[ 2 ]

HLA完全一致ドナーの候補がいない患者もHSCTを受けられるようにするべく、HLA複合体の単一のハプロタイプしか患者と一致しておらず、したがって半一致とされる同胞、両親、その他の血縁者を選択できるようにするための手法が開発されている。これまでに考案されたアプローチの大半は、幹細胞産物を患者に輸注する前のT細胞除去に基づいている。このアプローチに関連した主な課題は、免疫回復の遅れを伴う高度の免疫抑制であり、そうなると、致死的感染症の発生[ 41 ]、EBV関連リンパ増殖性疾患のリスク増大、および再発率の上昇につながる可能性がある。[ 42 ]結果として、生存率は一致ドナーからのHSCTと比べて不良となることから、この方法は、このアプローチの研究開発に主眼をおいた具体的な研究を勧めている比較的大規模な学術機関で主に行われている。

しかしながら、ハプロタイプ一致のアプローチが改善されたことで治療成績は改善しており、非血縁骨髄または臍帯血移植のアプローチと同程度の生存率が多くの研究グループから報告されている。[ 43 ][ 44 ][ 45 ][ 46 ]具体的な改善点としては以下のものがある:

数多くの種類があるハプロタイプ一致アプローチで報告されている生存率は25%~80%と幅があり、用いられる手法と対象となる患者のリスクに依存する。[ 42 ][ 43 ][ 52 ][ 53 ]; [ 54 ][証拠レベルC1] 成人を対象とした複数の後ろ向き研究により、ハプロタイプ一致ドナーからの移植では、一致非血縁ドナーからの移植や臍帯血移植と同程度の治療成績が得られることが示されている。[ 55 ][ 56 ]造血器腫瘍の成人患者を対象として強度減弱前処置レジメンを採用したランダム化試験では、ハプロタイプ一致ドナーを採用した患者において、無増悪生存期間は同程度であったが、再発率が低く、OSが良好であったことが示された。[ 57 ]ハプロタイプ一致ドナーを採用した小児試験では、骨髄破壊的前処置レジメンの方が治療成績が良好であったことが示され、生存期間はハプロタイプ不一致アプローチと同等である。[ 45 ][ 46 ][ 49 ][ 58 ]小児患者を対象とした試験では、ハプロタイプ一致アプローチを用いた方が、不一致非血縁ドナーアプローチと比べて無病生存期間(DFS)が良好であったことが示された。ハプロタイプ一致アプローチで治療を受けた患者のDFS率は、他の幹細胞ソースで治療を受けた患者のそれと同程度であった。[ 45 ]

HLA抗原に感作されており、ハプロタイプ一致ドナーの不一致アレル間に存在するHLAアレルに対する抗体が発現している患者では、ハプロタイプが一致した移植片に対して拒絶反応が起こるリスクが高い。臨床医は可能であれば、レシピエントが抗体を保有していないHLA型のドナーを選択すべきである。この問題に対する最善のアプローチに関するガイドラインが公表されている。[ 59 ]

幹細胞製品の比較

現在、血縁と非血縁の両条件で用いられている幹細胞ソースとして、以下の3つがある:

骨髄またはPBSCは、HLA部分一致(半分以上の抗原[ハプロタイプ一致])血縁ドナーのものも含めて、in vitroまたはin vivoでのT細胞除去後に使用できるが、この種の製品は他の幹細胞製品とは異なる挙動をする。幹細胞製品の比較を表3に示す。

表3.造血幹細胞製品の比較 PBSC 骨髄 臍帯血 T細胞除去後の骨髄/PBSC ハプロタイプ一致ドナーのT細胞除去後の骨髄/PBSC EBV-LPD = エプスタイン-バーウイルス関連リンパ増殖性疾患;GVHD = 移植片対宿主病;HSCT = 造血細胞移植;PBSC = 末梢血幹細胞。 aGVHDの発症は想定していない。患者がGVHDを発症した場合は、GVHDが軽快して免疫抑制を中止するまでの間、免疫再構築は遅延する。 bハプロタイプ一致ドナーを用いる場合は、免疫再構築までの期間が延長することがある。 T細胞の含有量 高い 中程度 低い 非常に低い 非常に低い CD34陽性細胞の含有量 中程度~高い 中程度 低い(ただし力価は高い) 中程度~高い 中程度~高い 好中球数回復までの期間 速やか:中央値16日(11~29日) [ 60 ] 中程度:中央値21日(12~35日) [ 60 ] 緩やか:中央値23日(11~133日) [ 33 ] 速やか:中央値16日(9~40日) [ 61 ] 速やか:中央値13日(10~20日) [ 62 ] 移植後早期の感染症、EBV-LPDのリスク 低い~中程度 中程度 高い 非常に高い 非常に高い 拒絶反応のリスク 低い 低い~中程度 中程度~高い 中程度~高い 中程度~高い 免疫再構築までの期間a 速やか(6~12カ月) 中程度(6~18カ月) 緩やか(6~24カ月) 緩やか(6~24カ月) 緩やか(9~24カ月)b 急性GVHDのリスク 中程度 中程度 中程度 低い 低い 慢性GVHDのリスク 高い 中程度 低い 低い 低い 製品間の主な違いは、含まれているT細胞およびCD34陽性前駆細胞の数である。T細胞数はPBSCでは非常に高く、骨髄では中程度で、臍帯血およびT細胞除去製品では低い。T細胞除去製品または臍帯血で移植を受けた患者では、一般に造血機能の回復が遅く、感染症のリスクが高く、免疫再構築が遅く、生着不成功のリスクが高く、EBV関連リンパ増殖性疾患のリスクが高い。これらのデメリットに対して、GVHDの発生率が低いことと、HLA完全一致ドナーを確保できない患者でも移植を検討できるという事実がメリットである。PBSCではT細胞とその他の細胞の数が多いほど、好中球数の回復と免疫再構築が早まるが、慢性GVHDの発生率も高くなる。

小児患者において異なる幹細胞ソース/製品での治療成績を直接比較した研究は数少ない。

証拠(小児における幹細胞ソース/製品別の治療成績の比較):

- 急性白血病に対してHSCTを受けた小児患者に関するレトロスペクティブ登録研究では、血縁ドナー骨髄移植を受けた患者が血縁ドナーPBSC移植を受けた患者と比較された。[ 63 ]

- 日本人の小児急性白血病患者を対象としたレトロスペクティブ研究では、PBSC移植を受けた患児90人が骨髄移植を受けた患児571人と比較された。[ 64 ]

- 非血縁ドナーを必要とする患者を対象としたBlood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Networkの大規模試験には、複数の小児患者が組み入れられた。被験者は骨髄移植とPBSC移植のいずれかにランダムに割り付けられた。この試験では以下のことが実証された:[ 65 ]

骨髄とPBSCを比較したプロスペクティブ研究が不足していることも相まって、これらの報告を受けて、小児を対象とする移植プロトコルの大半で血縁ドナーからのPBSCより骨髄が選択されるようになった。このアプローチは、レトロスペクティブ研究も含めたメタアナリシスによってさらに支持されている。[ 66 ]

非血縁移植における臍帯血と骨髄を比較した研究はレトロスペクティブなものであり、そのような解析に固有の問題を含んでいる。

証拠(非血縁移植における臍帯血と骨髄の治療成績の比較):

- ある研究では、HSCTとしてHLA 8/8一致の非血縁骨髄移植を受けた急性リンパ芽球性白血病(ALL)の小児患者が非血縁臍帯血移植を受けた小児ALL患者と比較された。[ 18 ]

- 被験者の大半が急性骨髄性白血病(AML)、骨髄異形成腫瘍(MDS)、およびALLの成人患者で構成された単一施設から報告された別の研究では、臍帯血移植の治療成績が一致および不一致非血縁ドナーからの骨髄/PBSC移植の治療成績と比較された。[ 67 ]

- CIBMTRは、2000年から2014年までに代替ドナー(HLA不一致の血縁または非血縁ドナー)からの移植を受けた低リスクおよび中リスクの小児ALLおよびAML患者を対象として、それぞれHLA 7/8一致の骨髄(n = 172)とHLA 4/6一致以上の臍帯血(n = 1,613)を用いた場合の治療成績を比較した。[ 72 ]

これらの研究結果に基づき、大半の移植施設では一致同胞骨髄が好ましい幹細胞ソース/移植片と考えられている。同胞ドナーが得られない場合は、完全一致非血縁ドナーの骨髄移植、十分な細胞数の単一ユニットからのHLA一致(4/6~6/6または6/8~8/8)臍帯血移植、またはハプロタイプ一致HSCTにより、同程度の生存率が得られる。[ 49 ][証拠レベルC2] 急性GVHDの予防に関する詳しい情報については、「小児における造血幹細胞移植後の合併症、移植片対宿主病、および晩期障害」の急性GVHDの予防のセクションを参照のこと。

治療成績に関連するその他のドナー特性

HLA一致度は同種HSCTにおける生存率の改善に関連する最も重要な因子であり続けているが、ほかにも多くのドナー特性が重要な治療成績に影響を及ぼすことが複数の研究によって示されている。血縁、非血縁、またはハプロタイプ一致の骨髄またはPBSCドナーを用いる場合には、ドナーから得られる細胞数の多さも重要であることが示されている。[ 73 ][ 74 ]詳細については、非血縁臍帯血HSCTにおけるHLAマッチングおよび細胞数に関する考慮事項のセクションを参照のこと。ドナーの年齢、血液型、CMV感染の有無、性別、女性ドナーの経産歴についても影響が研究されている。

理想的には、HLAマッチング後に、移植施設が以下の特性に基づいてドナーを選択するべきである:

ドナーとレシピエントのペアがこのアルゴリズムに完全に一致することはまれであり、これらの特性のどれを他の特性より優先するかの判断については議論がある。

証拠(ドナー-レシピエント特性):

- CIBMTR研究では、1988年から2006年までに造血器悪性腫瘍を理由に移植を受けた患者6,349人が調査された。同研究では、疾患リスクを始めとする重要な移植特性について調整をした上で、ドナー特性による影響が検討された。この研究で得られたデータから以下のことが示された:[ 76 ]

- EBMTの研究では、2007年から2011年までに移植を受けた患者4,690人のコホートを対象として、生存の独立した予測因子を調べる多変量解析が行われた。同研究により以下のことが実証された:[ 82 ]

- 10,000組を超える一致ペアを対象とした研究では、治療成績に影響を及ぼすと報告されているHLA以外の特性(ドナー年齢、性別、血液型、CMV感染状況など)に優先順位をつけられるようにする階層構造を定義することが試みられた。[ 83 ]

したがって、HLAマッチング後の時点で最適化するべき最も重要な因子はドナー年齢である可能性が高い。注意すべき点として、レシピエントがCMV陰性である場合には、CMV陰性のドナーを見つけることも優先度が高い。

いくつかの研究により、ハプロタイプの一致における最良のドナー特性を同定する試みがなされている。従来の骨髄移植と同様に、若年のドナーを選択するのが有益とみられるが、ドナーの性別については結論を下せるだけのデータが得られていない。強力なT細胞除去を行った研究では、母親をドナーとすることで治療成績が向上することが示されているが[ 84 ]、移植後にシクロホスファミドまたは強力な免疫抑制療法を用いた研究では、男性ドナーの方が良好のようであった。[ 85 ][ 86 ]この重要な問題を解明するにはさらなる研究が必要である。

ハプロタイプ一致ドナーを比較した大規模研究により、ABO不適合による生着への影響が示され(ABO適合とABO主不適合の比較で拒絶のリスクが6%から12%に倍増した)、双方向不適合のドナーから提供を受けた患者ではグレードII~IVの急性GVHDの発生率が2.4倍高かった。[ 87 ]ハプロタイプ不一致ドナーの場合と同様に、ハプロタイプ一致移植に若年ドナーを選択した場合、高齢ドナーと比較して治療成績の有意な改善が認められ、ドナー年齢の上昇によるHRの上昇幅は10年につき1.13であった。[ 88 ]

参考文献- Barker JN, Byam CE, Kernan NA, et al.: Availability of cord blood extends allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant access to racial and ethnic minorities. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16 (11): 1541-8, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Gragert L, Eapen M, Williams E, et al.: HLA match likelihoods for hematopoietic stem-cell grafts in the U.S. registry. N Engl J Med 371 (4): 339-48, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Woolfrey A, Klein JP, Haagenson M, et al.: HLA-C antigen mismatch is associated with worse outcome in unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 17 (6): 885-92, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Dehn J, Spellman S, Hurley CK, et al.: Selection of unrelated donors and cord blood units for hematopoietic cell transplantation: guidelines from the NMDP/CIBMTR. Blood 134 (12): 924-934, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Howard CA, Fernandez-Vina MA, Appelbaum FR, et al.: Recommendations for donor human leukocyte antigen assessment and matching for allogeneic stem cell transplantation: consensus opinion of the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN). Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (1): 4-7, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Shaw PJ, Kan F, Woo Ahn K, et al.: Outcomes of pediatric bone marrow transplantation for leukemia and myelodysplasia using matched sibling, mismatched related, or matched unrelated donors. Blood 116 (19): 4007-15, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Flomenberg N, Baxter-Lowe LA, Confer D, et al.: Impact of HLA class I and class II high-resolution matching on outcomes of unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation: HLA-C mismatching is associated with a strong adverse effect on transplantation outcome. Blood 104 (7): 1923-30, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Petersdorf EW, Kollman C, Hurley CK, et al.: Effect of HLA class II gene disparity on clinical outcome in unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia: the US National Marrow Donor Program Experience. Blood 98 (10): 2922-9, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Fernandez-Viña MA, Wang T, Lee SJ, et al.: Identification of a permissible HLA mismatch in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 123 (8): 1270-8, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Fernández-Viña MA, Klein JP, Haagenson M, et al.: Multiple mismatches at the low expression HLA loci DP, DQ, and DRB3/4/5 associate with adverse outcomes in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 121 (22): 4603-10, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Fleischhauer K, Shaw BE, Gooley T, et al.: Effect of T-cell-epitope matching at HLA-DPB1 in recipients of unrelated-donor haemopoietic-cell transplantation: a retrospective study. Lancet Oncol 13 (4): 366-74, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Crocchiolo R, Zino E, Vago L, et al.: Nonpermissive HLA-DPB1 disparity is a significant independent risk factor for mortality after unrelated hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 114 (7): 1437-44, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pidala J, Lee SJ, Ahn KW, et al.: Nonpermissive HLA-DPB1 mismatch increases mortality after myeloablative unrelated allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 124 (16): 2596-606, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Spellman S, Bray R, Rosen-Bronson S, et al.: The detection of donor-directed, HLA-specific alloantibodies in recipients of unrelated hematopoietic cell transplantation is predictive of graft failure. Blood 115 (13): 2704-8, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ciurea SO, Thall PF, Wang X, et al.: Donor-specific anti-HLA Abs and graft failure in matched unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 118 (22): 5957-64, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Shaw BE, Mayor NP, Szydlo RM, et al.: Recipient/donor HLA and CMV matching in recipients of T-cell-depleted unrelated donor haematopoietic cell transplants. Bone Marrow Transplant 52 (5): 717-725, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hurley CK, Woolfrey A, Wang T, et al.: The impact of HLA unidirectional mismatches on the outcome of myeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with unrelated donors. Blood 121 (23): 4800-6, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Zhang MJ, et al.: Outcomes of transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood and bone marrow in children with acute leukaemia: a comparison study. Lancet 369 (9577): 1947-54, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Eapen M, Klein JP, Ruggeri A, et al.: Impact of allele-level HLA matching on outcomes after myeloablative single unit umbilical cord blood transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Blood 123 (1): 133-40, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Eapen M, Wang T, Veys PA, et al.: Allele-level HLA matching for umbilical cord blood transplantation for non-malignant diseases in children: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Haematol 4 (7): e325-e333, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Takanashi M, Atsuta Y, Fujiwara K, et al.: The impact of anti-HLA antibodies on unrelated cord blood transplantations. Blood 116 (15): 2839-46, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cutler C, Kim HT, Sun L, et al.: Donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies predict outcome in double umbilical cord blood transplantation. Blood 118 (25): 6691-7, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Rocha V, Spellman S, Zhang MJ, et al.: Effect of HLA-matching recipients to donor noninherited maternal antigens on outcomes after mismatched umbilical cord blood transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 18 (12): 1890-6, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- van Rood JJ, Stevens CE, Smits J, et al.: Reexposure of cord blood to noninherited maternal HLA antigens improves transplant outcome in hematological malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 (47): 19952-7, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kanda J, Atsuta Y, Wake A, et al.: Impact of the direction of HLA mismatch on transplantation outcomes in single unrelated cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 19 (2): 247-54, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Stevens CE, Carrier C, Carpenter C, et al.: HLA mismatch direction in cord blood transplantation: impact on outcome and implications for cord blood unit selection. Blood 118 (14): 3969-78, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cunha R, Loiseau P, Ruggeri A, et al.: Impact of HLA mismatch direction on outcomes after umbilical cord blood transplantation for hematological malignant disorders: a retrospective Eurocord-EBMT analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant 49 (1): 24-9, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Barker JN, Rocha V, Scaradavou A: Optimizing unrelated donor cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 15 (1 Suppl): 154-61, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wagner JE, Barker JN, DeFor TE, et al.: Transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood in 102 patients with malignant and nonmalignant diseases: influence of CD34 cell dose and HLA disparity on treatment-related mortality and survival. Blood 100 (5): 1611-8, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Rubinstein P, Carrier C, Scaradavou A, et al.: Outcomes among 562 recipients of placental-blood transplants from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med 339 (22): 1565-77, 1998.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Barker JN, Weisdorf DJ, DeFor TE, et al.: Transplantation of 2 partially HLA-matched umbilical cord blood units to enhance engraftment in adults with hematologic malignancy. Blood 105 (3): 1343-7, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Michel G, Galambrun C, Sirvent A, et al.: Single- vs double-unit cord blood transplantation for children and young adults with acute leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood 127 (26): 3450-7, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wagner JE, Eapen M, Carter S, et al.: One-unit versus two-unit cord-blood transplantation for hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med 371 (18): 1685-94, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Stiff PJ, Montesinos P, Peled T, et al.: Cohort-Controlled Comparison of Umbilical Cord Blood Transplantation Using Carlecortemcel-L, a Single Progenitor-Enriched Cord Blood, to Double Cord Blood Unit Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 24 (7): 1463-1470, 2018.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Anand S, Thomas S, Hyslop T, et al.: Transplantation of Ex Vivo Expanded Umbilical Cord Blood (NiCord) Decreases Early Infection and Hospitalization. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 23 (7): 1151-1157, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wagner JE, Brunstein CG, Boitano AE, et al.: Phase I/II Trial of StemRegenin-1 Expanded Umbilical Cord Blood Hematopoietic Stem Cells Supports Testing as a Stand-Alone Graft. Cell Stem Cell 18 (1): 144-55, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Horwitz ME, Wease S, Blackwell B, et al.: Phase I/II Study of Stem-Cell Transplantation Using a Single Cord Blood Unit Expanded Ex Vivo With Nicotinamide. J Clin Oncol 37 (5): 367-374, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Delaney C, Heimfeld S, Brashem-Stein C, et al.: Notch-mediated expansion of human cord blood progenitor cells capable of rapid myeloid reconstitution. Nat Med 16 (2): 232-6, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Horwitz ME, Stiff PJ, Cutler C, et al.: Omidubicel vs standard myeloablative umbilical cord blood transplantation: results of a phase 3 randomized study. Blood 138 (16): 1429-1440, 2021.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Beatty PG, Clift RA, Mickelson EM, et al.: Marrow transplantation from related donors other than HLA-identical siblings. N Engl J Med 313 (13): 765-71, 1985.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Aversa F, Tabilio A, Velardi A, et al.: Treatment of high-risk acute leukemia with T-cell-depleted stem cells from related donors with one fully mismatched HLA haplotype. N Engl J Med 339 (17): 1186-93, 1998.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Barrett J, Gluckman E, Handgretinger R, et al.: Point-counterpoint: haploidentical family donors versus cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 17 (1 Suppl): S89-93, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Leung W, Campana D, Yang J, et al.: High success rate of hematopoietic cell transplantation regardless of donor source in children with very high-risk leukemia. Blood 118 (2): 223-30, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- González-Vicent M, Molina B, Andión M, et al.: Allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation using haploidentical donor vs. unrelated cord blood donor in pediatric patients: a single-center retrospective study. Eur J Haematol 87 (1): 46-53, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pulsipher MA, Ahn KW, Bunin NJ, et al.: KIR-favorable TCR-αβ/CD19-depleted haploidentical HCT in children with ALL/AML/MDS: primary analysis of the PTCTC ONC1401 trial. Blood 140 (24): 2556-2572, 2022.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Merli P, Algeri M, Galaverna F, et al.: TCRαβ/CD19 cell-depleted HLA-haploidentical transplantation to treat pediatric acute leukemia: updated final analysis. Blood 143 (3): 279-289, 2024.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Handgretinger R, Chen X, Pfeiffer M, et al.: Feasibility and outcome of reduced-intensity conditioning in haploidentical transplantation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1106: 279-89, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Locatelli F, Merli P, Pagliara D, et al.: Outcome of children with acute leukemia given HLA-haploidentical HSCT after αβ T-cell and B-cell depletion. Blood 130 (5): 677-685, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bertaina A, Zecca M, Buldini B, et al.: Unrelated donor vs HLA-haploidentical α/β T-cell- and B-cell-depleted HSCT in children with acute leukemia. Blood 132 (24): 2594-2607, 2018.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bethge WA, Faul C, Bornhäuser M, et al.: Haploidentical allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in adults using CD3/CD19 depletion and reduced intensity conditioning: an update. Blood Cells Mol Dis 40 (1): 13-9, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Leen AM, Christin A, Myers GD, et al.: Cytotoxic T lymphocyte therapy with donor T cells prevents and treats adenovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infections after haploidentical and matched unrelated stem cell transplantation. Blood 114 (19): 4283-92, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Huang XJ, Liu DH, Liu KY, et al.: Haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation without in vitro T-cell depletion for the treatment of hematological malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant 38 (4): 291-7, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Luznik L, Fuchs EJ: High-dose, post-transplantation cyclophosphamide to promote graft-host tolerance after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Immunol Res 47 (1-3): 65-77, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Berger M, Lanino E, Cesaro S, et al.: Feasibility and Outcome of Haploidentical Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation with Post-Transplant High-Dose Cyclophosphamide for Children and Adolescents with Hematologic Malignancies: An AIEOP-GITMO Retrospective Multicenter Study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 22 (5): 902-9, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Baker M, Wang H, Rowley SD, et al.: Comparative Outcomes after Haploidentical or Unrelated Donor Bone Marrow or Blood Stem Cell Transplantation in Adult Patients with Hematological Malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 22 (11): 2047-2055, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Rashidi A, Slade M, DiPersio JF, et al.: Post-transplant high-dose cyclophosphamide after HLA-matched vs haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation for AML. Bone Marrow Transplant 51 (12): 1561-1564, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Fuchs EJ, O'Donnell PV, Eapen M, et al.: Double unrelated umbilical cord blood vs HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation: the BMT CTN 1101 trial. Blood 137 (3): 420-428, 2021.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Symons HJ, Zahurak M, Cao Y, et al.: Myeloablative haploidentical BMT with posttransplant cyclophosphamide for hematologic malignancies in children and adults. Blood Adv 4 (16): 3913-3925, 2020.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ciurea SO, Cao K, Fernandez-Vina M, et al.: The European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Consensus Guidelines for the Detection and Treatment of Donor-specific Anti-HLA Antibodies (DSA) in Haploidentical Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 53 (5): 521-534, 2018.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bensinger WI, Martin PJ, Storer B, et al.: Transplantation of bone marrow as compared with peripheral-blood cells from HLA-identical relatives in patients with hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med 344 (3): 175-81, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Rocha V, Cornish J, Sievers EL, et al.: Comparison of outcomes of unrelated bone marrow and umbilical cord blood transplants in children with acute leukemia. Blood 97 (10): 2962-71, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bertaina A, Merli P, Rutella S, et al.: HLA-haploidentical stem cell transplantation after removal of αβ+ T and B cells in children with nonmalignant disorders. Blood 124 (5): 822-6, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Eapen M, Horowitz MM, Klein JP, et al.: Higher mortality after allogeneic peripheral-blood transplantation compared with bone marrow in children and adolescents: the Histocompatibility and Alternate Stem Cell Source Working Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. J Clin Oncol 22 (24): 4872-80, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Shinzato A, Tabuchi K, Atsuta Y, et al.: PBSCT is associated with poorer survival and increased chronic GvHD than BMT in Japanese paediatric patients with acute leukaemia and an HLA-matched sibling donor. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60 (9): 1513-9, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, et al.: Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med 367 (16): 1487-96, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Shimosato Y, Tanoshima R, Tsujimoto SI, et al.: Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplantation versus Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation for Hematologic Malignancies in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 26 (1): 88-93, 2020.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Milano F, Gooley T, Wood B, et al.: Cord-Blood Transplantation in Patients with Minimal Residual Disease. N Engl J Med 375 (10): 944-53, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ruggeri A, Michel G, Dalle JH, et al.: Impact of pretransplant minimal residual disease after cord blood transplantation for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in remission: an Eurocord, PDWP-EBMT analysis. Leukemia 26 (12): 2455-61, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bachanova V, Burke MJ, Yohe S, et al.: Unrelated cord blood transplantation in adult and pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: effect of minimal residual disease on relapse and survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 18 (6): 963-8, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Sutton R, Shaw PJ, Venn NC, et al.: Persistent MRD before and after allogeneic BMT predicts relapse in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 168 (3): 395-404, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Sanchez-Garcia J, Serrano J, Serrano-Lopez J, et al.: Quantification of minimal residual disease levels by flow cytometry at time of transplant predicts outcome after myeloablative allogeneic transplantation in ALL. Bone Marrow Transplant 48 (3): 396-402, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Mehta RS, Holtan SG, Wang T, et al.: GRFS and CRFS in alternative donor hematopoietic cell transplantation for pediatric patients with acute leukemia. Blood Adv 3 (9): 1441-1449, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pulsipher MA, Chitphakdithai P, Logan BR, et al.: Donor, recipient, and transplant characteristics as risk factors after unrelated donor PBSC transplantation: beneficial effects of higher CD34+ cell dose. Blood 114 (13): 2606-16, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Aversa F, Terenzi A, Tabilio A, et al.: Full haplotype-mismatched hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a phase II study in patients with acute leukemia at high risk of relapse. J Clin Oncol 23 (15): 3447-54, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kollman C, Howe CW, Anasetti C, et al.: Donor characteristics as risk factors in recipients after transplantation of bone marrow from unrelated donors: the effect of donor age. Blood 98 (7): 2043-51, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kollman C, Spellman SR, Zhang MJ, et al.: The effect of donor characteristics on survival after unrelated donor transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Blood 127 (2): 260-7, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Boeckh M, Nichols WG: The impact of cytomegalovirus serostatus of donor and recipient before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the era of antiviral prophylaxis and preemptive therapy. Blood 103 (6): 2003-8, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Seebach JD, Stussi G, Passweg JR, et al.: ABO blood group barrier in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation revisited. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 11 (12): 1006-13, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Logan AC, Wang Z, Alimoghaddam K, et al.: ABO mismatch is associated with increased nonrelapse mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (4): 746-54, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Stussi G, Muntwyler J, Passweg JR, et al.: Consequences of ABO incompatibility in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 30 (2): 87-93, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Loren AW, Bunin GR, Boudreau C, et al.: Impact of donor and recipient sex and parity on outcomes of HLA-identical sibling allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 12 (7): 758-69, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Canaani J, Savani BN, Labopin M, et al.: ABO incompatibility in mismatched unrelated donor allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: A report from the acute leukemia working party of the EBMT. Am J Hematol 92 (8): 789-796, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Shaw BE, Logan BR, Spellman SR, et al.: Development of an Unrelated Donor Selection Score Predictive of Survival after HCT: Donor Age Matters Most. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 24 (5): 1049-1056, 2018.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Stern M, Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, et al.: Survival after T cell-depleted haploidentical stem cell transplantation is improved using the mother as donor. Blood 112 (7): 2990-5, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ciurea SO, Champlin RE: Donor selection in T cell-replete haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: knowns, unknowns, and controversies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 19 (2): 180-4, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang Y, Chang YJ, Xu LP, et al.: Who is the best donor for a related HLA haplotype-mismatched transplant? Blood 124 (6): 843-50, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Canaani J, Savani BN, Labopin M, et al.: Impact of ABO incompatibility on patients' outcome after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia - a report from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the EBMT. Haematologica 102 (6): 1066-1074, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- DeZern AE, Franklin C, Tsai HL, et al.: Relationship of donor age and relationship to outcomes of haploidentical transplantation with posttransplant cyclophosphamide. Blood Adv 5 (5): 1360-1368, 2021.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 同種造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)の前処置レジメン

-

造血幹細胞(骨髄、末梢血幹細胞[PBSC]、または臍帯血)を輸注する前の数日間には、レシピエントに対して化学療法/免疫療法が行われ、ときに放射線療法も併用される。これは前処置レジメンと呼ばれており、この治療の当初の目的は以下の通りであった:

ドナーT細胞は生着を容易にし、移植片対白血病(GVL)効果により腫瘍を傷害する(骨髄に余地を作る必要をなくし、がんを集中的に治療する)ことが認識されているため、骨髄除去よりむしろ免疫抑制に焦点を置いた強度を減弱ないし最小限に抑えたHSCTのアプローチが開発されている。それらのレジメンにより毒性が低下した結果として、移植関連死亡率が低下するとともに、標準のHSCTアプローチでは重度の毒性作用が生じるリスクが高い比較的高齢の患者やHSCT施行時点で併存症がある若年の患者が同種HSCTに適格となる可能性が広がっている。[ 1 ]

現在利用可能な前処置レジメンは、それぞれで生じる免疫抑制や骨髄抑制の程度が極めて大きく異なり、強度が最も低いクラスのレジメンは移植片対腫瘍(GVT)効果に大きく依存している(図3を参照のこと)。

図3.最新の定義において骨髄非破壊的、強度減弱、または骨髄破壊的に分類されている小児HSCTで頻用される主な前処置レジメン。FLU + treosulfanとFLU + ブスルファン(最大量)は骨髄破壊的とみなされるが、これらや同様のアプローチは毒性軽減(reduced-toxicity)レジメンと呼ばれている。 これらのレジメンは発生する骨髄抑制および免疫抑制の程度が異なるが、臨床的に以下の3つの主要カテゴリーに分類されている(図4を参照):[ 2 ]

図4.汎血球減少の持続期間と造血幹細胞移植の必要性に基づき分類された前処置レジメンの3つのカテゴリー。骨髄破壊的レジメン(MA)は、不可逆的な汎血球減少を引き起こし、造血幹細胞移植を必要とする。骨髄非破壊的レジメン(NMA)は、最小限の血球減少を引き起こし、造血幹細胞移植を必要としない。強度減弱レジメン(RIC)は、MAとNMAのどちらにも分類できないレジメンである。Elsevierから許諾を得て転載:Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Volume 15 (Issue 12), Andrea Bacigalupo, Karen Ballen, Doug Rizzo, Sergio Giralt, Hillard Lazarus, Vincent Ho, Jane Apperley, Shimon Slavin, Marcelo Pasquini, Brenda M. Sandmaier, John Barrett, Didier Blaise, Robert Lowski, Mary Horowitz, Defining the Intensity of Conditioning Regimens: Working Definitions, Pages 1628-1633, Copyright 2009. 複数のレトロスペクティブ研究による長年にわたる検討の結果、強度減弱アプローチと骨髄破壊的アプローチで治療成績が同程度であったことが示された。[ 3 ][ 4 ]しかしながら、急性骨髄性白血病(AML)および骨髄異形成腫瘍(MDS)の成人患者を骨髄破壊的アプローチと強度減弱アプローチいずれかによるHSCTを受ける2群にランダムに割り付けたBlood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Networkの試験により、レジメン強度の重要性が実証された。[ 5 ]

この点を考慮して、強度減弱および骨髄非破壊的レジメンの採用は、より強力な骨髄破壊的アプローチに耐えられない比較的高齢の成人でよく確立されているが[ 6 ][ 7 ][ 8 ]、これらのアプローチが評価された研究では若年の悪性腫瘍患者の症例数が限られている。[ 9 ][ 10 ][ 11 ][ 12 ][ 13 ]Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortiumの大規模研究では、骨髄破壊的レジメンの採用時に移植関連死亡のリスクを高める患者因子(例、骨髄破壊的移植の既往、重度の臓器系機能不全、活動性の浸潤性真菌感染症)が同定されるとともに、強度減弱レジメンでの治療が成功した。[ 14 ]この高リスク群では移植関連死亡率が低く、移植時点で腫瘍が検出されないか最小限しか検出されなかった患者の大半で長期生存が得られた。これらのアプローチでは再発リスクが高くなるため、小児がんに対する採用は現在のところ骨髄破壊的レジメンに不適格な患者に限定されており、微小残存病変(MRD)陰性の寛解を達成した患者で成功の可能性が最も高くなる。[ 14 ]

小児に対するHSCTでは、骨髄破壊的であるが従来の非常に強力な骨髄破壊的アプローチ(最大線量での全身照射、ブスルファンとシクロホスファミド、またはブスルファン、シクロホスファミド、メルファランなど)でみられる重度の毒性は引き起こさない前処置レジメンを開発する努力がなされている。それらの比較的強度の低いレジメンは毒性軽減(reduced toxicity)レジメンと呼ばれており、具体的には最大量のブスルファンとフルダラビンまたはトレオスルファンとフルダラビンなどのアプローチがある。これらのアプローチは、完全キメリズムを必要とする良性疾患に対する移植で特に有用性が示されているが[ 15 ]、悪性疾患の患者に用いられた場合にも同様の治療成績を示すことが多い。[ 16 ]

ドナーキメリズムの確立

強力な骨髄破壊的アプローチではほぼ常に、移植に血球数が回復し次第、ドナー細胞由来の造血が確立される。HSCTへの毒性軽減、強度減弱、および骨髄非破壊的前処置の導入によって、ドナー造血への移行はより緩徐(部分的なドナー造血から完全なドナー造血まで数カ月かけて徐々に移行する)なものとなり、ときに完全なドナー造血に至らない状態が長期間続くこともある。ドナー造血をレシピエント造血と区別するためのDNAベースの手法が確立されており、HSCT後の造血の全体または一部がドナーとレシピエントどちらに由来するものかを記述する用語としてキメリズムが用いられている。

HSCTレシピエントが達成するドナーキメリズムのペースおよび程度については、いくつかの意義がある。強度減弱または骨髄非破壊的前処置を受けた患者では、完全なドナーキメリズムへの迅速な移行は再発率の低下につながる一方、移植片対宿主病(GVHD)が増加する。[ 17 ]強度減弱前処置後の完全なドナーキメリズム達成の遅れは、HSCT後6~7カ月後にみられる晩期発症型の急性GVHDにつながっている(骨髄破壊的アプローチでは一般に移植後100日以内にみられる)。[ 18 ]一部の患者はドナー造血とレシピエント造血の両方が安定する混合キメリズムを達成する。混合キメリズムには、悪性腫瘍に対するHSCT後の再発増加やGVHDの減少との関連が認められる。しかしながら、基礎にある病態の是正に正常な造血能の一部しか必要とならず、GVHDが有益とならない良性疾患に対するHSCTでは、この状態はしばしば有利となる。[ 19 ]最後に、経時的な測定におけるドナーキメリズムの低下(特にT細胞特異的キメリズムの場合)には、拒絶リスクの増大との関連が報告されている。[ 20 ]

レシピエントキメリズムが持続することにも一定の意味があるため、大半の移植プログラムでは、生着後すぐにキメリズムの検査を行い、完全なドナー造血が達成されて安定するまで定期的な検査が継続される。レシピエントキメリズムの増加に関連した再発および拒絶のリスク増大に対処するために、免疫抑制療法の迅速な中止とドナーリンパ球輸注(DLI)という2つのアプローチが定義されている。これらのアプローチはこの問題の対処法として頻用されており、再発リスクを低下させ、一部の症例では拒絶反応を止める効果が示されている。[ 21 ][ 22 ][ 23 ]ドナーキメリズムを増加ないし安定化させるための免疫抑制とその漸減のタイミングやDLIのアプローチは、幹細胞ソースにより異なる。また、施設間のばらつきも大きく、積極的にキメリズムを追跡して頻回に介入する施設もあれば、介入を制限するアプローチを採用している施設もある。詳細については、GVL効果を増強するためのドナーリンパ球輸注(DLI)の施行または免疫抑制療法の早期中止のセクションを参照のこと。

参考文献- Deeg HJ, Sandmaier BM: Who is fit for allogeneic transplantation? Blood 116 (23): 4762-70, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, et al.: Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 15 (12): 1628-33, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Luger SM, Ringdén O, Zhang MJ, et al.: Similar outcomes using myeloablative vs reduced-intensity allogeneic transplant preparative regimens for AML or MDS. Bone Marrow Transplant 47 (2): 203-11, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pulsipher MA, Chitphakdithai P, Logan BR, et al.: Donor, recipient, and transplant characteristics as risk factors after unrelated donor PBSC transplantation: beneficial effects of higher CD34+ cell dose. Blood 114 (13): 2606-16, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Scott BL, Pasquini MC, Logan BR, et al.: Myeloablative Versus Reduced-Intensity Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndromes. J Clin Oncol 35 (11): 1154-1161, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Giralt S, Estey E, Albitar M, et al.: Engraftment of allogeneic hematopoietic progenitor cells with purine analog-containing chemotherapy: harnessing graft-versus-leukemia without myeloablative therapy. Blood 89 (12): 4531-6, 1997.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Slavin S, Nagler A, Naparstek E, et al.: Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation and cell therapy as an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplantation with lethal cytoreduction for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Blood 91 (3): 756-63, 1998.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Storb R, Yu C, Sandmaier BM, et al.: Mixed hematopoietic chimerism after marrow allografts. Transplantation in the ambulatory care setting. Ann N Y Acad Sci 872: 372-5; discussion 375-6, 1999.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bradley MB, Satwani P, Baldinger L, et al.: Reduced intensity allogeneic umbilical cord blood transplantation in children and adolescent recipients with malignant and non-malignant diseases. Bone Marrow Transplant 40 (7): 621-31, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Del Toro G, Satwani P, Harrison L, et al.: A pilot study of reduced intensity conditioning and allogeneic stem cell transplantation from unrelated cord blood and matched family donors in children and adolescent recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant 33 (6): 613-22, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Gómez-Almaguer D, Ruiz-Argüelles GJ, Tarín-Arzaga Ldel C, et al.: Reduced-intensity stem cell transplantation in children and adolescents: the Mexican experience. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 9 (3): 157-61, 2003.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pulsipher MA, Woolfrey A: Nonmyeloablative transplantation in children. Current status and future prospects. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 15 (5): 809-34, vii-viii, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Roman E, Cooney E, Harrison L, et al.: Preliminary results of the safety of immunotherapy with gemtuzumab ozogamicin following reduced intensity allogeneic stem cell transplant in children with CD33+ acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 11 (19 Pt 2): 7164s-7170s, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pulsipher MA, Boucher KM, Wall D, et al.: Reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation in pediatric patients ineligible for myeloablative therapy: results of the Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium Study ONC0313. Blood 114 (7): 1429-36, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cseh A, Galimard JE, de la Fuente J, et al.: Busulfan-fludarabine- or treosulfan-fludarabine-based conditioning before allogeneic HSCT from matched sibling donors in paediatric patients with sickle cell disease: A study on behalf of the EBMT Paediatric Diseases and Inborn Errors Working Parties. Br J Haematol 204 (1): e1-e5, 2024.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pulsipher MA, Ahn KW, Bunin NJ, et al.: KIR-favorable TCR-αβ/CD19-depleted haploidentical HCT in children with ALL/AML/MDS: primary analysis of the PTCTC ONC1401 trial. Blood 140 (24): 2556-2572, 2022.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Baron F, Baker JE, Storb R, et al.: Kinetics of engraftment in patients with hematologic malignancies given allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Blood 104 (8): 2254-62, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Vigorito AC, Campregher PV, Storer BE, et al.: Evaluation of NIH consensus criteria for classification of late acute and chronic GVHD. Blood 114 (3): 702-8, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Marsh RA, Vaughn G, Kim MO, et al.: Reduced-intensity conditioning significantly improves survival of patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 116 (26): 5824-31, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- McSweeney PA, Niederwieser D, Shizuru JA, et al.: Hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with hematologic malignancies: replacing high-dose cytotoxic therapy with graft-versus-tumor effects. Blood 97 (11): 3390-400, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bader P, Kreyenberg H, Hoelle W, et al.: Increasing mixed chimerism is an important prognostic factor for unfavorable outcome in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation: possible role for pre-emptive immunotherapy? J Clin Oncol 22 (9): 1696-705, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Horn B, Soni S, Khan S, et al.: Feasibility study of preemptive withdrawal of immunosuppression based on chimerism testing in children undergoing myeloablative allogeneic transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant 43 (6): 469-76, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Haines HL, Bleesing JJ, Davies SM, et al.: Outcomes of donor lymphocyte infusion for treatment of mixed donor chimerism after a reduced-intensity preparative regimen for pediatric patients with nonmalignant diseases. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (2): 288-92, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 同種造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)の免疫療法としての効果

-

移植片対白血病(GVL)効果

HSCTに関する初期の研究では、強力な骨髄破壊的前処置の施行と、それに続く自家または同種骨髄による造血系の回復に焦点が置かれていた。その後の研究により、同種移植では腫瘍抗原に対する骨髄移植片の免疫療法的反応によって再発リスクが低下することが、すぐに明らかにされた。この現象はGVLまたは移植片対腫瘍(GVT)効果と呼ばれるようになり、主要とマイナー両方のHLA抗原不一致との関連が示されている。

GVLは臨床的な移植片対宿主病(GVHD)と強く関連した現象であるため、GVL効果を治療目的で利用することは容易ではない。HSCTに対する標準的なアプローチでは、軽度または中程度のGVHD(急性骨髄性白血病[AML]ではグレードIまたはII、急性リンパ芽球性白血病[ALL]ではグレードI~III)がみられた患者で生存率が最も高くなるのに対し、GVHDを発症しない患者では再発が多くなり、重度のGVHDがみられた患者では移植関連死亡が多くなる。[ 1 ][ 2 ][ 3 ]; [ 4 ][証拠レベルC2]

GVLの発生時期やGVLを至適に活用する方法を解明するのは容易ではない。研究方法の1つとしては、ある疾患に対して骨髄破壊的HSCTを受けた患者の再発率および生存率を自家移植の場合と同種移植の場合で比較することである。

特定の疾患に対するGVL/GVTの治療上の有益性については、強度減弱前処置レジメンの使用経験からさらなる洞察が得られている。前処置レジメンの強度が高いことは大半の症例において治癒の十分条件ではないため、この移植アプローチはGVLに依存している。患者が標準的な移植に適格でない場合にこのアプローチの採用が有益となることが研究により示されているが[ 8 ]、小児がん患者では一般に骨髄破壊的アプローチを安全に採用できることから、このアプローチはHSCTを必要とする小児がん患者の大半において用いられていない。詳細については、同種HSCTの準備レジメンのセクションを参照のこと。

GVL効果を増強するためのドナーリンパ球輸注(DLI)の施行または免疫抑制療法の早期中止

移植後に腫瘍を特異的または非特異的な標的とする細胞を輸注することで、治療を目的としてGVLを誘導することができる。最も一般的なアプローチはDLIである。このアプローチの成否は、移植後にドナーT細胞の生着が長く維持されることによって、GVL誘導のために輸注されたドナーリンパ球への拒絶反応が回避されるかどうかにかかっている。

移植後に再発したCML患者では治療的なDLIによって強い反応が得られるが(60%~80%が長期寛解)[ 9 ]、他の疾患(AMLおよびALL)の患者で得られる反応はそれほど強くなく、長期生存率は20%~30%に過ぎない。[ 10 ]早期再発した疾患活動性の高い急性白血病患者では、DLIは良好に機能しない。晩期再発(移植後6カ月以上)とDLI前の化学療法で完全寛解を達成した患者の治療に、良好な治療成績との関連が報告されている。[ 11 ]GVLを増強するために改変を加えたドナーリンパ球やその他のドナー細胞(ナチュラルキラー[NK]細胞など)の輸注も研究されているが、まだ一般には採用されていない。

治療目的でGVLを誘導する別の方法は、HSCT後の免疫抑制療法の早期中止である。ドナーの種類に応じて免疫抑制療法の漸減を早期に計画した研究もあれば(血縁ドナーでは非血縁ドナーよりGVHDのリスクが低いため、より速やかに漸減する)、再発リスクを評価して免疫抑制療法の早期漸減のタイミングを図るために、高感度の方法を用いて、わずかに残存するレシピエント細胞(レシピエントキメリズム)または微小残存病変を測定している研究もある。

レシピエントキメリズムが持続/進行しているために再発リスクが高くなっている患者の再発を回避するためにHSCT後の免疫抑制療法の早期中止とDLIを併用する方法が、ALLまたはAMLに対して移植を受けた患者を対象に検証されている。[ 12 ][証拠レベルB4]; [ 13 ][証拠レベルC2]

評価段階にある他の免疫療法および細胞療法のアプローチ

HSCTにおけるキラー免疫グロブリン様受容体(KIR)不一致の役割

HSCT後の状況では、ドナー由来NK細胞が以下を促進することが示されている:[ 16 ][ 17 ][ 18 ]

NK細胞の機能は、いくつかの受容体ファミリー(活性化型および抑制型KIRを含む)との相互作用によって修飾される。同種HSCTの状況におけるKIRの効果は、ドナー由来NK細胞上の特異的な抑制型KIRの発現と、レシピエントの白血病および正常細胞上の一致したHLA クラスI分子(KIRリガンド)の有無に依存する。正常では、対になった抑制型KIR分子と相互作用する特異的なKIRリガンドが存在することで、NK細胞の正常細胞に対する攻撃が抑止される。同種移植の状況では、レシピエントの白血病細胞はドナーのNK細胞と遺伝的に異なっており、適切な抑制型KIRリガンドを発現していないと考えられる。ドナー-レシピエント間の遺伝的な組合せによっては、リガンドと受容体の不一致により、NK細胞によるレシピエント白血病細胞の殺傷が進行する。

特定のKIR-リガンドの組合せで再発率が低下することがT細胞除去ハプロタイプ一致移植において最初に観察され、それはAMLに対するHSCT後に最も顕著であった。[ 17 ][ 19 ]しかしながら、ハプロタイプ一致移植でこの効果が認められなかった研究もある。[ 20 ]これらの研究から、適切なKIR-リガンドの組合せでは、再発率の低下とともに、GVHDも減少することが示唆されている。その後の多くの研究では、標準の移植方法を用いたKIR不適合HSCTに生存期間の延長効果が検出されず[ 21 ][ 22 ][ 23 ][ 24 ]、このことから、T細胞除去を行って他の形態をとる抑制型の細胞相互作用を排除する必要があるかもしれないとの結論に至っている。

T細胞が相対的少ない移植法である臍帯血HSCTでは、ドナー-レシピエント間でKIRリガンド不適合がある場合に、再発率が低く、生存率が高くなることが指摘されている。[ 25 ][ 26 ]この知見とは対照的に、KIR不一致の一部の組合せ(活性化型受容体KIR2DS1とHLA C1リガンド)はAML患者に対するT細胞除去なしのHSCTにおいて再発率の低下につながることが、ある研究で実証された。[ 27 ]同胞ドナーHSCTやAML以外の疾患におけるKIR不適合の意義については議論があるが、小児を対象とした研究では、少なくとも2つの研究グループから、ALLにおける特定の種類のKIR不一致で治療成績が良好であったことが報告されている。[ 28 ][ 29 ][ 30 ]

KIRの研究に関連した現在の課題は、何をもってKIR不適合とするかと、ドナー-レシピエントペアにおけるKIR分子の最も好ましい組合せが何であるかを決定するのに、いくつかの異なるアプローチが用いられていることである。[ 19 ][ 31 ][ 32 ]活性化型のKIR分子もこの効果に寄与することが示されている。[ 33 ]KIRの分類の標準化とプロスペクティブ研究が、このアプローチの有用性および重要性を明確化する助けになるはずである。ハプロタイプ一致HSCTを行っている施設は限られており、また臍帯血HSCTの他のアプローチの研究結果は予備的なものに過ぎないため、大半の移植プログラムでは、ドナーを選択するための戦略の一部としてKIR不一致を採用していない。HLAの完全一致が治療成績に最も重要と考えられており、KIR不一致の検討や良好なKIR活性化プロファイルを有するドナーの選択は依然として二次的なアプローチである。

NK細胞移植

ハプロタイプ一致HSCT後の状況ではGVHDのリスクが低く、再発を減少させる有効性が実証されていることから、NK細胞の輸注が高リスク患者に対する治療法および寛解例に対する地固め療法として研究されている。

証拠(NK細胞移植の治療成績):

- University of Minnesotaの研究グループは、互いに異なるNK細胞集団を用いたアプローチを比較した。[ 34 ]

- St. Jude Children’s Research Hospitalの研究チームは、化学療法を完了して寛解状態にある中リスクAML患者10人に対して治療を行った。それらの患者は低用量で免疫抑制療法を受けた後、地固め療法としてハプロタイプ一致NK細胞の輸注とIL-2の投与を受けた。[

35

]

この高リスクAMLコホートの初期の生存率は高かったが、これらのアプローチによるNK細胞療法の有効性を確立するには、検証的な多施設共同研究が必要である。

- HSCTの前後に拡大培養/活性化処理を行ったNK細胞を使用している研究チームもある。[ 36 ]膜結合型IL-21を用いてハプロタイプ一致NK細胞の培養を行うアプローチの一つでは、著しい増殖と高い活性が認められた。それらの細胞はその後、ハプロタイプ一致HSCTの直前に輸注された後、HSCTの7日後および28日後にも追加で輸注された。[ 36 ]

参考文献- Yeshurun M, Weisdorf D, Rowe JM, et al.: The impact of the graft-versus-leukemia effect on survival in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv 3 (4): 670-680, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pulsipher MA, Langholz B, Wall DA, et al.: The addition of sirolimus to tacrolimus/methotrexate GVHD prophylaxis in children with ALL: a phase 3 Children's Oncology Group/Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium trial. Blood 123 (13): 2017-25, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Neudorf S, Sanders J, Kobrinsky N, et al.: Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for children with acute myelocytic leukemia in first remission demonstrates a role for graft versus leukemia in the maintenance of disease-free survival. Blood 103 (10): 3655-61, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Boyiadzis M, Arora M, Klein JP, et al.: Impact of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease on Late Relapse and Survival on 7,489 Patients after Myeloablative Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 21 (9): 2020-8, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Woods WG, Neudorf S, Gold S, et al.: A comparison of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, autologous bone marrow transplantation, and aggressive chemotherapy in children with acute myeloid leukemia in remission. Blood 97 (1): 56-62, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ribera JM, Ortega JJ, Oriol A, et al.: Comparison of intensive chemotherapy, allogeneic, or autologous stem-cell transplantation as postremission treatment for children with very high risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: PETHEMA ALL-93 Trial. J Clin Oncol 25 (1): 16-24, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Gross TG, Hale GA, He W, et al.: Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for refractory or recurrent non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children and adolescents. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16 (2): 223-30, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pulsipher MA, Boucher KM, Wall D, et al.: Reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation in pediatric patients ineligible for myeloablative therapy: results of the Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium Study ONC0313. Blood 114 (7): 1429-36, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Porter DL, Collins RH, Shpilberg O, et al.: Long-term follow-up of patients who achieved complete remission after donor leukocyte infusions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 5 (4): 253-61, 1999.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Levine JE, Barrett AJ, Zhang MJ, et al.: Donor leukocyte infusions to treat hematologic malignancy relapse following allo-SCT in a pediatric population. Bone Marrow Transplant 42 (3): 201-5, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Warlick ED, DeFor T, Blazar BR, et al.: Successful remission rates and survival after lymphodepleting chemotherapy and donor lymphocyte infusion for relapsed hematologic malignancies postallogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 18 (3): 480-6, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Horn B, Petrovic A, Wahlstrom J, et al.: Chimerism-based pre-emptive immunotherapy with fast withdrawal of immunosuppression and donor lymphocyte infusions after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for pediatric hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (4): 729-37, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Horn B, Wahlstrom JT, Melton A, et al.: Early mixed chimerism-based preemptive immunotherapy in children undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 64 (8): , 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bader P, Kreyenberg H, Hoelle W, et al.: Increasing mixed chimerism is an important prognostic factor for unfavorable outcome in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation: possible role for pre-emptive immunotherapy? J Clin Oncol 22 (9): 1696-705, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Rettinger E, Willasch AM, Kreyenberg H, et al.: Preemptive immunotherapy in childhood acute myeloid leukemia for patients showing evidence of mixed chimerism after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood 118 (20): 5681-8, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, et al.: Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science 295 (5562): 2097-100, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Giebel S, Locatelli F, Lamparelli T, et al.: Survival advantage with KIR ligand incompatibility in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from unrelated donors. Blood 102 (3): 814-9, 2003.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bari R, Rujkijyanont P, Sullivan E, et al.: Effect of donor KIR2DL1 allelic polymorphism on the outcome of pediatric allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 31 (30): 3782-90, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Capanni M, et al.: Donor natural killer cell allorecognition of missing self in haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: challenging its predictive value. Blood 110 (1): 433-40, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Merli P, Algeri M, Galaverna F, et al.: TCRαβ/CD19 cell-depleted HLA-haploidentical transplantation to treat pediatric acute leukemia: updated final analysis. Blood 143 (3): 279-289, 2024.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Davies SM, Ruggieri L, DeFor T, et al.: Evaluation of KIR ligand incompatibility in mismatched unrelated donor hematopoietic transplants. Killer immunoglobulin-like receptor. Blood 100 (10): 3825-7, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Farag SS, Bacigalupo A, Eapen M, et al.: The effect of KIR ligand incompatibility on the outcome of unrelated donor transplantation: a report from the center for international blood and marrow transplant research, the European blood and marrow transplant registry, and the Dutch registry. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 12 (8): 876-84, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Davies SM, Iannone R, Alonzo TA, et al.: A Phase 2 Trial of KIR-Mismatched Unrelated Donor Transplantation Using in Vivo T Cell Depletion with Antithymocyte Globulin in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia: Children's Oncology Group AAML05P1 Study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 26 (4): 712-717, 2020.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Verneris MR, Miller JS, Hsu KC, et al.: Investigation of donor KIR content and matching in children undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute leukemia. Blood Adv 4 (7): 1350-1356, 2020.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cooley S, Trachtenberg E, Bergemann TL, et al.: Donors with group B KIR haplotypes improve relapse-free survival after unrelated hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 113 (3): 726-32, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Willemze R, Rodrigues CA, Labopin M, et al.: KIR-ligand incompatibility in the graft-versus-host direction improves outcomes after umbilical cord blood transplantation for acute leukemia. Leukemia 23 (3): 492-500, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Venstrom JM, Pittari G, Gooley TA, et al.: HLA-C-dependent prevention of leukemia relapse by donor activating KIR2DS1. N Engl J Med 367 (9): 805-16, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Leung W: Use of NK cell activity in cure by transplant. Br J Haematol 155 (1): 14-29, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Leung W, Campana D, Yang J, et al.: High success rate of hematopoietic cell transplantation regardless of donor source in children with very high-risk leukemia. Blood 118 (2): 223-30, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Oevermann L, Michaelis SU, Mezger M, et al.: KIR B haplotype donors confer a reduced risk for relapse after haploidentical transplantation in children with ALL. Blood 124 (17): 2744-7, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Leung W, Iyengar R, Triplett B, et al.: Comparison of killer Ig-like receptor genotyping and phenotyping for selection of allogeneic blood stem cell donors. J Immunol 174 (10): 6540-5, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pulsipher MA, Ahn KW, Bunin NJ, et al.: KIR-favorable TCR-αβ/CD19-depleted haploidentical HCT in children with ALL/AML/MDS: primary analysis of the PTCTC ONC1401 trial. Blood 140 (24): 2556-2572, 2022.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cooley S, Weisdorf DJ, Guethlein LA, et al.: Donor selection for natural killer cell receptor genes leads to superior survival after unrelated transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 116 (14): 2411-9, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Miller JS, Soignier Y, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, et al.: Successful adoptive transfer and in vivo expansion of human haploidentical NK cells in patients with cancer. Blood 105 (8): 3051-7, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Rubnitz JE, Inaba H, Ribeiro RC, et al.: NKAML: a pilot study to determine the safety and feasibility of haploidentical natural killer cell transplantation in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 28 (6): 955-9, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ciurea SO, Schafer JR, Bassett R, et al.: Phase 1 clinical trial using mbIL21 ex vivo-expanded donor-derived NK cells after haploidentical transplantation. Blood 130 (16): 1857-1868, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 臨床評価段階にある治療選択肢

-

米国国立がん研究所(NCI)が支援している臨床試験に関する情報は、NCIウェブサイトに掲載されている。他の組織がスポンサーを務める臨床試験に関する情報については、ClinicalTrials.govのウェブサイトを参照のこと。

以下は、現在実施されている国および/または医療機関が主導する臨床試験の例である:

- 本要約の最終更新(2024/06/13)

-

PDQがん情報要約は、定期的にレビューされ、新たな情報が得られ次第更新される。このセクションでは、上記の日付で本要約に加えられた最新の変更内容を記載する。

本要約は包括的にレビューされた。

本要約の作成および更新作業はPDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Boardが行っており、同委員会は編集面においてNCIから独立している。本要約は独自の文献レビューの結果を反映するものであり、NCIまたはNIHの方針声明を示すものではない。PDQ要約の更新におけるPDQ編集委員会の要約方針および役割に関する詳しい情報については、本PDQ要約についておよびPDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionalsのページを参照のこと。

- 本PDQ要約について

-

本要約の目的

医療専門家向けの本PDQがん情報要約では、小児がんの治療における同種造血幹細胞移植の利用について、専門家の査読を経た、証拠に基づく情報を包括的に提供している。本要約は、患者を治療する臨床家に情報を与え支援するための情報資源として作成されている。医療上の意思決定のための正式なガイドラインや推奨事項を提供するものではない。

査読者および更新情報

本要約は編集作業において米国国立がん研究所(NCI)とは独立したPDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Boardにより定期的にレビューされ、随時更新される。本要約は独自の文献レビューの結果を反映するものであり、NCIまたは米国国立衛生研究所(NIH)の方針声明を示すものではない。

委員会のメンバーは毎月、直近で発表された記事をレビューし、個々の記事について以下を行うべきかどうかを判断する:

要約の変更は、発表された記事の証拠の強さを委員会のメンバーが評価し、記事を本要約にどのように組み入れるべきかを決定するコンセンサス過程を経て行われる。

本要約の内容についてコメントまたは質問がある場合は、NCIウェブサイトのEmail UsからCancer.govに連絡されたい。要約に関する質問またはコメントについて委員会のメンバー個人に連絡することを禁じる。委員会のメンバーは個別の問い合わせには対応しない。

証拠レベル

本要約で引用されている参考文献の一部には証拠レベルの指定が明記されている。それらの指定は、読者が特定の介入またはアプローチの利用を支持している証拠の強さを評価する上で参考になることを意図したものである。PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Boardは、証拠レベルの指定を策定するにあたり公式順位分類を使用している。

本要約の使用許可

PDQは登録商標である。PDQ文書の内容は本文として自由に使用できるが、完全な形で記し定期的に更新しなければ、NCI PDQがん情報要約として特定することはできない。ただし、著者は“NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: 【本要約からの抜粋】.”のような一文を記載することができる。

本PDQ要約の好ましい引用は以下の通りである:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Pediatric Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/hp-stem-cell-transplant/allogeneic. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 35133766]

本要約内の画像は、PDQ要約内での使用に限って著者、イラストレーター、および/または出版社の許可を得て使用されている。PDQ情報以外での画像の使用許可は、所有者から得る必要があり、米国国立がん研究所(National Cancer Institute)が付与できるものではない。本要約内のイラストの使用に関する情報は、多くの他のがん関連画像とともにVisuals Online(2,000以上の科学画像を収蔵)で入手できる。

免責条項

入手可能な証拠の強さに基づき、治療選択肢は「標準」または「臨床評価段階にある」のいずれかで記載される。これらの分類は、保険払い戻しの決定基準として使用されるべきものではない。保険の適用範囲に関する詳しい情報については、Cancer.govのManaging Cancer Careページで入手できる。

お問い合わせ

Cancer.govウェブサイトについての問い合わせまたはヘルプの利用に関する詳しい情報は、Contact Us for Helpページに掲載されている。質問はウェブサイトのEmail UsからもCancer.govに送信可能である。

画像を拡大する

画像を拡大する