ご利用について

医療専門家向けの本PDQがん情報要約では、小児がんの治療のための造血幹細胞移植後にみられる合併症、移植片対宿主病、および晩期障害について、専門家の査読を経た、証拠に基づく情報を包括的に提供している。本要約は、患者を治療する臨床家に情報を与え支援するための情報資源として作成されている。医療上の意思決定のための正式なガイドラインや推奨事項を提供するものではない。

本要約は編集作業において米国国立がん研究所(NCI)とは独立したPDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Boardにより定期的にレビューされ、随時更新される。本要約は独自の文献レビューの結果を反映するものであり、NCIまたは米国国立衛生研究所(NIH)の方針声明を示すものではない。

CONTENTS

- 移植関連死亡のリスクに影響する移植前の併存疾患:造血細胞移植特異的併存疾患指数の予測力

-

移植の過程に伴う治療は強度が高いため、レシピエントの移植前の臨床状態(例:年齢、感染症や臓器不全の存在、機能的状態)は移植関連死亡のリスクに関連している。

移植後の治療成績に対する移植前の併存疾患の影響を評価するための最適なツールが、既存の併存疾患の尺度であるチャールソン併存疾患指数(CCI)を改変して開発された。Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Centerの研究者らにより、CCIの要素のいずれが成人および小児患者における移植関連死亡に相関しているかが系統的に規定された。また研究者らによって、移植患者に特異的に予測力を有するいくつかの追加の併存疾患も確認された。

この指数は妥当性が確認され、現在は造血細胞移植特異的併存疾患指数(HCT-CI)と呼ばれている。[ 1 ][ 2 ]移植関連死亡率は、心臓、肝臓、肺、消化管、感染性、および自己免疫性の併存疾患、または以前の固形腫瘍の病歴があると増加する(表1を参照のこと)。

表1.造血細胞移植特異的併存疾患指数(HCT-CI)に含まれている併存疾患の定義a HCT-CIのスコア 1 2 3 AST/ALT = アスパラギン酸アミノトランスフェラーゼ/アラニンアミノトランスフェラーゼ;DLCO = 一酸化炭素拡散能;FEV1 = 一秒量;ULN = 正常値の上限。 a出典:Sorror et al.[ 1 ] b医学的治療、ステント、バイパス移植を要する1枝以上の冠動脈狭窄。 不整脈:心房細動または心房粗動、洞不全症候群、あるいは心室性不整脈 肺の中等度の併存疾患:DLCOおよび/またはFEV1が66%~80%、あるいは軽微な活動での呼吸困難 心臓弁膜症:僧帽弁逸脱を除く 心臓の併存疾患:冠動脈疾患b、うっ血性心不全、心筋梗塞、または駆出率が50%以下 腎臓の中等度/重度の併存疾患:血清クレアチニン値 > 2 mg/dL、透析を受けている、または以前の腎移植 肝臓の中等度/重度の併存疾患:肝硬変、ビリルビン > 1.5 × ULN、またはAST/ALT > 2.5 × ULN 脳血管疾患:一過性脳虚血発作または脳血管障害 消化性潰瘍:治療を必要とする 以前の固形腫瘍:非黒色腫皮膚がんを除いて、患者の病歴のあらゆる時点において治療されたもの 糖尿病:インスリンまたは経口の血糖降下薬による治療を必要とするもの(ただし、食事制限単独は含まない) リウマチ:全身性エリテマトーデス、関節リウマチ、多発性筋炎、混合結合組織病、またはリウマチ性多発筋痛 肺の重度の併存疾患:DLCOおよび/またはFEV1が65%未満、あるいは安静時のまたは酸素投与を要する呼吸困難 肝臓の軽度の併存疾患:慢性肝炎、ビリルビン > ULNまたはAST/ALT > ULN~2.5 × ULN 感染症:治療の最初から抗菌薬による治療の継続が必要なもの 炎症性腸疾患:クローン病または潰瘍性大腸炎 肥満:肥満指数 > 35kg/m2 精神障害:精神科医の診察または治療を必要とするうつ病または不安 この指数の予測精度は移植関連死亡率と全生存率(OS)の両方に対して高く、スコア3以上の患者をスコア0の患者と比較した場合の非再発死亡のハザード比は3.54(95%信頼区間[CI]、2.0-6.3)、生存のハザード比は2.69(95%CI、1.8-4.1)であった。元の研究は強力な骨髄破壊的アプローチを受けた患者を対象に実施されたものであったが、HCT-CIは強度減弱および骨髄非破壊的前処置を受けた患者でも成績を予測できることが示されている。[ 3 ]HCT-CIはまた、疾患の状態[ 4 ]およびKarnofskyスコア[ 5 ]と組み合わされて用いられており、生存期間の予測精度がさらに向上している。また、HCT-CIスコアが高い(> 3)場合は、グレードIII~IVの急性移植片対宿主病のリスクが高くなっている。[ 6 ]

HCT-CIの研究で評価された患者のほとんどは成人であり、一覧に示された併存疾患は成人病に偏っている。小児および若年成人の造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)レシピエントに対するこの尺度の関連性が複数の研究で調査されている。

証拠(小児におけるHCT-CIスコアの使用):

- 広範な悪性および良性疾患の小児患者(年齢中央値6歳)を対象とするレトロスペクティブコホート研究が4つの大規模施設で実施された。[

7

]

- HCT-CIは非再発死亡と生存の両方の予測に役立った。

- 1年非再発死亡率は以下の通りであった:

- 1年OS率は以下の通りであった:

- 2つ目の研究では、若年成人(16~39歳)を対象として、以下のことが実証された:[ 8 ]

- Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant ResearchによるHCT-CIのプロスペクティブな妥当性確認では、2007年から2009年に移植を受けた患者23,876人(うち1,755人が小児)が対象とされた。患者のHCT-CIスコアと転帰が追跡された。[ 9 ]

これらの研究において報告された併存疾患のほとんどが呼吸器系または肝疾患および感染症であった。[ 7 ][ 8 ]青年および若年成人を対象とした研究では、HSCT前に肺機能不全がみられた患者は特に予後不良となるリスクが高く、2年OS率は29%であったのに対し、HSCT前の肺機能が正常であった患者では61%であった。[ 8 ]

参考文献- Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al.: Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood 106 (8): 2912-9, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- ElSawy M, Storer BE, Pulsipher MA, et al.: Multi-centre validation of the prognostic value of the haematopoietic cell transplantation- specific comorbidity index among recipient of allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation. Br J Haematol 170 (4): 574-83, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Sorror ML, Storer BE, Maloney DG, et al.: Outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with nonmyeloablative or myeloablative conditioning regimens for treatment of lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 111 (1): 446-52, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Sorror ML, Sandmaier BM, Storer BE, et al.: Comorbidity and disease status based risk stratification of outcomes among patients with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplasia receiving allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 25 (27): 4246-54, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Sorror M, Storer B, Sandmaier BM, et al.: Hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index and Karnofsky performance status are independent predictors of morbidity and mortality after allogeneic nonmyeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cancer 112 (9): 1992-2001, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Sorror ML, Martin PJ, Storb RF, et al.: Pretransplant comorbidities predict severity of acute graft-versus-host disease and subsequent mortality. Blood 124 (2): 287-95, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Smith AR, Majhail NS, MacMillan ML, et al.: Hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index predicts transplantation outcomes in pediatric patients. Blood 117 (9): 2728-34, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wood W, Deal A, Whitley J, et al.: Usefulness of the hematopoietic cell transplantation-specific comorbidity index (HCT-CI) in predicting outcomes for adolescents and young adults with hematologic malignancies undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplant. Pediatr Blood Cancer 57 (3): 499-505, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Sorror ML, Logan BR, Zhu X, et al.: Prospective Validation of the Predictive Power of the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Comorbidity Index: A Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research Study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (8): 1479-87, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 広範な悪性および良性疾患の小児患者(年齢中央値6歳)を対象とするレトロスペクティブコホート研究が4つの大規模施設で実施された。[

7

]

- 造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)関連急性合併症

-

移植後の感染症リスクおよび免疫回復

免疫再構築不良は移植片のソースに関係なく、HSCT成功の大きな障壁である。[ 1 ][ 2 ]重篤な感染症は、HSCT後の晩期死亡の大きな割合(4%~20%)を占めている。[ 3 ]

免疫能回復を有意に遅らせる因子としては以下のものがある:[ 4 ]

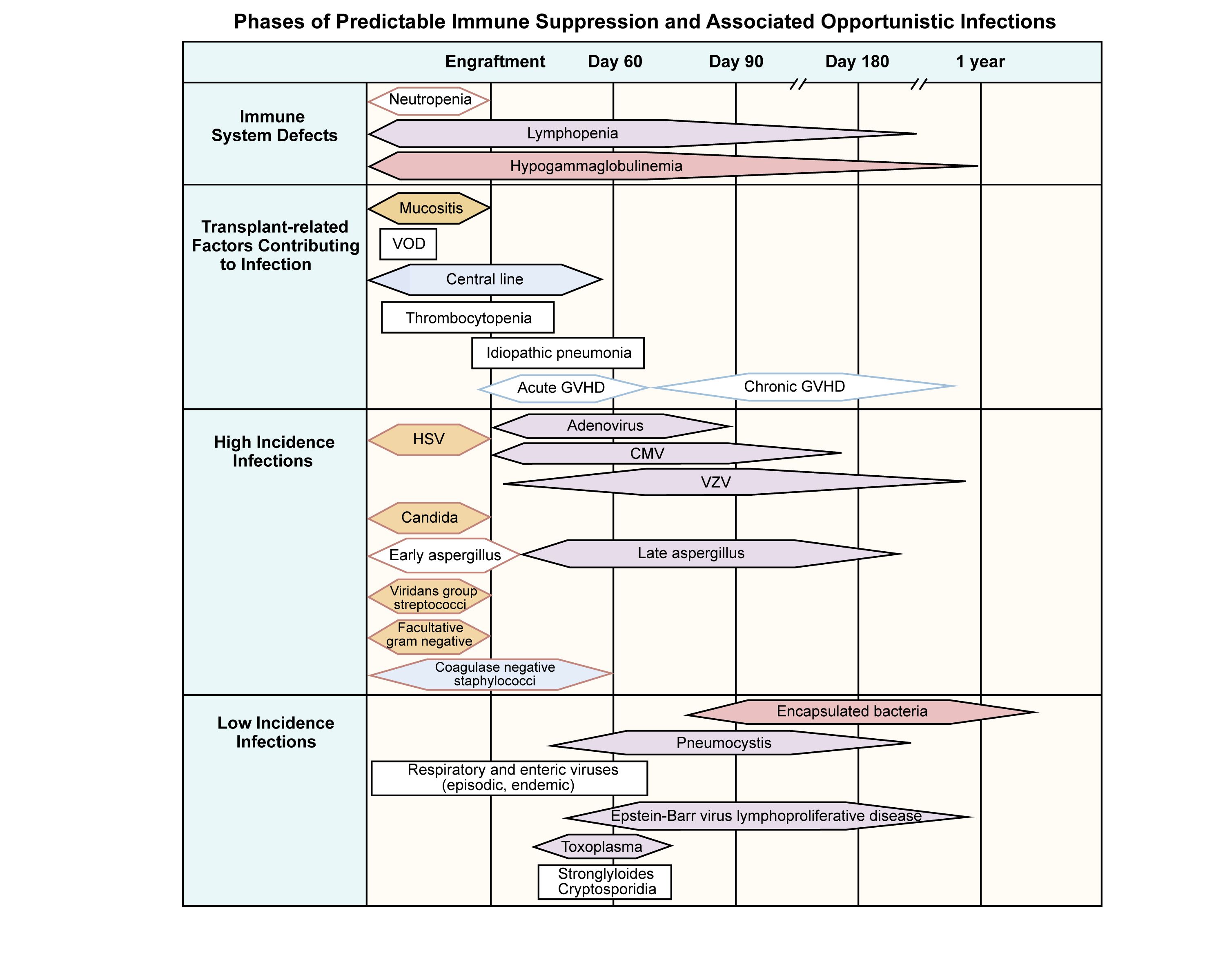

図1は、同種移植後に発生する免疫の欠陥、寄与する移植関連因子、および感染症の種類と時期を示す。[ 5 ]

図1.同種造血幹細胞移植レシピエントにおける予測可能な免疫抑制とそれに伴う日和見感染の時期。出典:Burik and Freifeld.この図は以下に掲載されたものである:Clinical Oncology, 3rd edition, Abeloff et al., Chapter: Infection in the severely immunocompromised patient, Pages 941-956, Copyright Elsevier (2004). 細菌感染は移植後数週間の好中球減少期に発生する傾向があり、この時期には前処置レジメンにより粘膜バリアが損傷している。好中球減少期における予防的抗菌薬投与の役割について重要な研究が進行中である。[ 6 ]

米国疾病予防管理センター(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)、Infectious Disease Society of America、およびAmerican Society of Transplantation and Cellular Therapyの共同作業により、HSCT後の感染予防のためのガイドラインが策定された。[ 7 ]アプローチとしては、予防的な抗ウイルス薬、抗真菌薬、および抗菌薬の投与、感染症の徴候に応じた経験的治療の強化、HSCT後の免疫低下状態の全期間を通じた注意深いモニタリングの継続などがある。

真菌感染に対する予防は移植後最初の数カ月間は標準であり、真菌感染のリスクが高い慢性GVHD患者に検討されうる。抗真菌薬による予防は、患者の基礎にある免疫状態に合わせて個別に対応しなければならない。ニューモシスチス感染症は骨髄移植後のすべての患者で発生する可能性があり、予防が必須である。[ 6 ];[ 8 ][証拠レベルC1]

HSCT(特にT細胞除去または臍帯血移植)後のウイルス感染は、死亡の主な原因となりうる。ウイルス感染症の種類としては以下のものがある:

高リスクの同種移植では、注意深いウイルス感染モニタリングが不可欠である。

中心静脈ラインを留置している患者と有意な慢性GVHDがある患者では、晩期に細菌感染症が発生することがある。これらの患者は、莢膜を有する微生物(特に肺炎球菌)に感染しやすい。再免疫にもかかわらず、これらの患者はときに有意な感染症を発症することがあり、予防接種に対する血清学的反応が示されるまで予防の継続が推奨される。場合によっては、同種HSCT後の患者は機能的に無脾状態となることがあり、抗菌薬の予防的投与が推奨される。免疫が回復するまで患者は感染症の予防(例:[Pneumocystis jirovecii]肺炎予防)を継続すべきである。免疫回復までの期間はさまざまであるが、自家HSCT後は3~9カ月で、同種HSCT後にGVHDが認められない場合は9~24カ月に及ぶ。活動性の慢性GVHD患者は、何年も免疫抑制が持続しうる。多くの施設で、感染症リスクに対する指針として骨髄移植後にT細胞サブセットの回復を監視している。[ 6 ]

移植後のワクチン接種

国際的な移植および感染症グループにより、自家および同種移植後のワクチン接種に関する具体的なガイドラインが作成されている。[ 6 ][ 11 ][ 12 ][ 13 ]移植後のワクチン接種の理想的な時期を明らかにすることを目指した比較研究は実施されていないが、表2に概説したワクチンのガイドラインにより、ワクチン接種を受けるほとんどの患者で防御的抗体価が得られる。これらのガイドラインでは、自家移植レシピエントに対して幹細胞注入後6カ月経過時に予防接種を開始し、移植から24カ月後に生ワクチンを投与するように推奨している。同種移植を受けた患者は、移植後6カ月経過すれば予防接種を開始できる。しかしながら、多くのグループは、免疫抑制剤の投与を継続する患者に対しては移植後12カ月経過するまで、または患者が免疫抑制薬の投与を中止するまで待機することを好む。

地域的流行または流行性疾患集団発生の時点で、ワクチン接種の推奨を考慮すべきである。このような状況では、宿主反応が限られていることを認識したうえで、死菌ワクチンを用いたより早期のワクチン接種を実施してもよい。HSCT後のワクチンに関する最近更新されたコンセンサスガイドラインには、SARS-CoV-2ワクチンに関する推奨が盛り込まれている。[ 13 ]初期の研究では防御免疫の獲得に有効であることが示されていたが、ウイルスの経時的変化を考慮して、SARS-CoV-2に対するワクチン接種のアプローチについては現在も研究が進められている。[ 14 ]

表2.造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)レシピエントに対するワクチン接種のスケジュールa 自家HSCT 6カ月 8カ月 12カ月 24カ月 同種HSCT(HSCT後12カ月が経過する前に予防接種を受けていない場合;GVHDの有無や免疫抑制療法中かどうかにかかわらず開始する) 12カ月 14カ月 18カ月 24カ月 GVHD = 移植片対宿主病。 a出典:Tomblyn et al.[ 6 ]、疾病予防管理センター[ 7 ]、およびKumar et al.[ 15 ] b示されている時期は移植(0日目)後の時期である。 cDTapが利用できない場合は、Tdapを使用してもよい。 d小児患者および免疫抑制中(前回のワクチン接種後、最低6~8週間)に予防接種を受けたGVHD患者に対しては抗体価が考慮されることがある。 eHSCT後4カ月経過するか、CD4数が200/mcLを超える患者ではそれ以前に、または流行している場合はいつでも開始できる。HSCT後、6カ月未満で接種する場合は2回目の接種が必要となる場合がある。9歳未満の小児には、1カ月間隔を空けて2回目の接種が必要である。 fワクチン接種前と後(少なくとも接種後6~8週間)の抗体価を考慮する。 gGVHD患者に対してのみ24カ月経過時にPCV 7;他の患者はすべてPPV 23を接種可能である。 h小児患者は少なくとも1カ月の間隔を空けて2回の接種を受けるべきである。 不活化ワクチン ジフテリア・破傷風・無細胞百日咳(DTap) Xc Xc Xc、d インフルエンザ菌(Hib) X X Xd B型肝炎(HepB) X X Xd 不活化ポリオ(IPV) X X Xd インフルエンザ、季節性接種(筋注) Xe 肺炎球菌結合型(PCV 7、PCV 13) Xf X Xd、f、g 肺炎球菌多糖体(PPV 23) Xd、f、g 弱毒生ワクチン(活動性のGVHDまたは免疫抑制の状態にある患者では禁忌) 麻疹・ムンプス・風疹 Xd、h 任意の不活化ワクチン A型肝炎 任意 髄膜炎菌 Xd(高リスク患者に対して) 任意の生ワクチン(活動性のGVHDまたは免疫抑制の状態にある患者では禁忌) 水痘 任意 狂犬病 曝露した場合は、12~24カ月時点なら考慮してもよい 黄熱、ダニ媒介脳炎(TBE)、B型日本脳炎 流行地域への旅行に際して 禁忌のワクチン 経鼻インフルエンザワクチン(3価弱毒生インフルエンザワクチン):家庭内接触者と介護者は、HSCTレシピエントと接触をもつ前の2週間に帯状疱疹ワクチン、BCG、経口ポリオワクチン(OPV)、コレラワクチン、腸チフスワクチン(経口、筋注)、ロタウイルスワクチンの接種を受けるべきではない。 類洞閉塞症候群/静脈閉塞疾患(SOS/VOD)

病理学的に、肝臓のSOS/VODは肝類洞に対する損傷の結果であり、胆道閉塞を引き起こす。この症候群は、骨髄破壊的移植を受けた小児患者の15%~40%に発生すると推定されている。[ 16 ][ 17 ]

SOS/VODの危険因子としては以下のものがある:[ 16 ][ 17 ]

SOS/VODは以下により臨床的に定義されている:

致死的なSOS/VODは一般に、移植直後に発生し、多臓器不全を特徴とする。[ 18 ]これより軽度で可逆性のSOS/VODが起こることもあり、完全回復が期待できる。ビリルビン値の上昇を伴わない重度のSOS/VODを有する小児患者が報告されている。[ 19 ]このため、ビリルビン値の上昇を来さずに他の症状を示す患者のモニタリングについて警戒を怠らないことが重要である。

SOS/VODの診断

SOS/VODの古い定義には、改訂Seattle基準またはBaltimore基準がある。

これらの定義は、遅発性SOS/VODとビリルビン値正常のVODを判別できないため不十分であり、小児科診療では特に問題が大きい。

European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation(EBMT)は改訂版の基準を公表しており、現在広く用いられている。[ 22 ]その基準では、組織学的に証明された場合か、血行動態検査または超音波検査でSOS/VODの所見(肝腫大、腹水、門脈の血流低下または逆流)が認められた場合に、遅発性SOS/VODと判定できる。また、小児患者を想定した修正も加えられており[ 23 ]、SOS/VODの発症時期に制限はなく、以下のうち2つ以上が必要とされている:

- 原因不明の消耗性および輸血抵抗性の血小板減少症

- 利尿薬の使用にもかかわらず3日間連続で原因不明の体重増加がみられる場合、またはベースライン値から5%を超える体重増加がみられる場合

- ベースライン値を超える肝腫大(画像検査による確認が望ましい)

- ベースライン値を超える腹水(画像検査による確認が望ましい)

- ベースライン値を超えるビリルビン値の上昇が3日間続く、またはビリルビン値が72時間以内に2 mg/dL以上まで上昇する

さらに修正した診断アルゴリズム(Cairo/Cooke基準)が提唱されており、まれな状況でみられる症状にも柔軟に対応できるようになっている。[ 24 ]EBMTおよびCairo/Cookeの基準は、臨床試験でプロスペクティブに検証されたものではない。

SOS/VODの予防および治療

ヘパリン、プロテインC、アンチトロンビンIIIなどの薬剤を用いた予防および治療のアプローチが研究されているが、結果はさまざまである。[ 25 ]1つの単一施設による小規模レトロスペクティブ研究により、コルチコステロイド療法の有益性が示されたが、さらなる妥当性の確認が必要である。[ 26 ]

活性が実証されている別の薬剤として、微小血管内皮に対して抗血栓および線維素溶解作用を有するオリゴヌクレオチド混合物であるデフィブロチドがある。デフィブロチドの研究では以下のことが示されている:

米国食品医薬品局(FDA)は、HSCT後に腎臓または肺の機能不全を伴う肝臓SOS/VODを有する患者に対する治療薬としてデフィブロチドを承認した。

SOS/VODの診断および管理に関して証拠に基づく推奨が、British Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation(BSBMT)により発表された。[ 30 ]生検は鑑別が難しい症例にのみ使用し、経頸静脈アプローチを用いて実施すべきであると推奨されている。BSBMTは、SOS/VODの予防にデフィブロチドの使用(現在、デフィブロチドによる予防は米国の適応に含まれていない)を支持しているが、プロスタグランジンE1、ペントキシフィリン、またはアンチトロンビンの使用を支持するにはデータが不十分であると主張している。また、SOS/VODの治療では、積極的な体液平衡の管理、救命救急および胃腸科の専門医による早期の関与、およびデフィブロチドと場合によってはメチルプレドニゾロンの使用を推奨している。しかし、組織プラスミノーゲンアクチベータまたはN-アセチルシステインの使用を支持する証拠は不十分であると結論付けた。[ 30 ][ 35 ]Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigatorsと協働しているPediatric Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Consortiumは、HSCT後の小児におけるSOS/VODの診断および管理に対するコンセンサスを得たより詳細な推奨を公表した。[ 36 ][ 37 ][ 38 ]

移植関連血栓性微小血管症(TA-TMA)

TA-TMAは臨床的に溶血性尿毒症症候群に酷似しているが、その原因および臨床経過は他の溶血性尿毒症症候群様の疾患とは異なる。諸研究により、この症候群と補体経路の崩壊との関連が示されている。[ 39 ]TA-TMAは、カルシニューリン阻害薬のタクロリムスおよびシクロスポリンの使用と最も頻繁に関連しており、これらの医薬品のいずれかがシロリムスと併用された場合により頻繁に発生することが指摘されている。[ 40 ]

この症候群の診断基準は、専門家の統一見解に基づいて更新されており、2014年に公表された基準を修正したものである(表3を参照のこと)。[ 41 ][ 42 ]

表3.TMA Harmonization Panel Consensus Recommended Diagnostic Criteria, Modified Jodele Criteriaa 生検で病変(腎臓または消化管)が証明されたているか、または 臨床基準:14日以内に連続する2つの時点で以下の7つの基準のうち4つ以上を満たさなければならない AIHA = 自己免疫性溶血性貧血;LDH = 乳酸脱水素酵素;pRBC = 濃厚赤血球液;rUPCR = 随時尿の尿蛋白/クレアチニン比;ULN = 正常範囲上限。 aSchoettler et al.から許諾を得て転載したものであり、Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND licenseの下で入手可能である。[ 41 ] bJodele et al.の公表された基準に基づく。[ 43 ] 貧血b 以下のいずれかと定義する: 1.好中球生着を示す所見が認められるにもかかわらず、輸血非依存を達成できない 2.ヘモグロビン値が患者のベースラインから1 g/dL低下 3.新たな輸血依存 貧血の他の原因を除外する(AIHAやPRCAなど) 血小板減少b 以下のいずれかと定義する: 1.血小板生着を達成できない 2.血小板輸血の必要性が予想より高い 3.血小板輸血に反応しない 4.最大限の血小板生着後に血小板数がベースライン値から50%以上減少 LDH高値 > 年齢別ULN 破砕赤血球 あり 高血圧 年齢別99パーセンタイルを上回るか(18歳未満)、収縮期血圧 ≥ 140 mmHgまたは拡張期血圧 ≥ 90 mmHg(18歳以上) sC5b-9値の上昇 ≥ ULN 蛋白尿 rUPCRが1 mg/mg以上 証拠(HSCTの成績に対するTA-TMAの影響):

- 小児患者を対象としたTA-TMAの多施設共同研究では、以下に示すTA-TMAの定義が用いられた:[

44

]

- TA-TMAの組織学的所見が認められるか、

- TA-TMAの診断の決め手になる以下の臨床検査および臨床マーカーのうち4つ以上が認められること:

- 乳酸脱水素酵素(LDH)値が年齢別基準値を超えている。

- 末梢血塗抹標本で破砕赤血球を認める。

- De novoの血小板減少または血小板輸血の必要性が生じている。

- De novoの貧血または赤血球輸血の必要性が生じている。

- 年齢別99パーセンタイルを超える高血圧(18歳未満)または2剤以上の降圧剤を必要とする140/90 mmHgの高血圧(18歳以上)がある。

- 随時尿による2回の尿検査で尿蛋白が30 mg/dL以上であるか、随時尿の尿蛋白/クレアチニン比が1 mg/mgを超える。

- 終末補体活性化:血漿sC5b-9値が正常範囲を超えて上昇している(244ng/mL以上)。

- この研究では以下の結果が実証された:

- 同種または自家HSCTを受けた連続する614人の患者において、同種移植患者の19%と自家移植患者の10%がTA-TMAを発症した。

- TA-TMAを発症した患者では、急性GVHDおよびステロイド抵抗性GVHD、ICU入室、侵襲的換気補助、心嚢液貯留、肺高血圧症、透析または持続的腎代替療法、急性腎障害、およびVODの発生率が高かった。

- 同種HSCTでは、最初の6カ月間の治療関連死亡率がTA-TMAのある患者の方がTA-TMAのない患者より有意に高かった(20% vs 3%;P ≤ 0.0001)。

- 自家HSCTでは、最初の6カ月間の全生存(OS)率がTA-TMAのある患者の方がTA-TMAのない患者より有意に低かった(79% vs 98%;P = 0.001)。

TA-TMAの治療

TA-TMAの治療には以下のものがある:

- カルシニューリン阻害薬の中止および必要であれば他の免疫抑制薬による代用。

- 高血圧に加え、必要であれば透析による腎障害の注意深い管理。

疾患の原因がカルシニューリン阻害薬単独である場合、腎機能が正常であっても予後は一般に不良である。しかしながら、カルシニューリン阻害薬とシロリムスの併用に関連するTA-TMAの大半は、シロリムスの中止後および一部の症例では両方の薬剤の中止後に回復している。[ 40 ]

腎機能の温存において補体調節(c5、エクリズマブ療法)の役割を示唆する証拠もある。この合併症の治療におけるこの薬剤の役割のさらなる評価が実施中である。[ 45 ][ 46 ][ 47 ]TA-TMAの治療にエクリズマブを使用するランダム化試験は実施されていないが、単施設および多施設共同のレトロスペクティブ研究と1つの臨床試験から得られたデータが公表されている。歴史的に見て、未治療の高リスクTA-TMA患者の1年生存率は約20%であった。[ 48 ]エクリズマブの使用を検討した2つのレトロスペクティブ研究では、既存対照と比較して良好な生存率が示された。単一施設の研究では、エクリズマブ治療による1年OS率が66%であることが示され[ 48 ]、多施設共同研究では6カ月OS率が47%と報告された。[ 49 ]

証拠(エクリズマブによる高リスクTA-TMAの治療):

ある多施設共同試験では、多臓器機能障害がある高リスクTA-TMAの患者21人が登録された。エクリズマブの投与レジメンは、集中負荷期、導入期、および維持期で構成される最長24週間の治療であった。[ 42 ]

- 主要評価項目に有意差が認められ、HSCT後6カ月時点でのOS率は71%であった(無治療の既存対照では18%;P < 0.0001)。

- 15人の生存者のうち11人(73%)は報告時点で臓器機能が完全に回復していた。

特発性肺炎症候群(IPS)

IPSは、ドナー細胞注入後14~90日の間に起こる非感染性のびまん性肺障害を特徴とする。考えられる病因としては、前処置レジメンによる直接の毒性作用および高濃度の炎症性サイトカインを肺胞に分泌させる潜在感染が挙げられる。[ 50 ]

IPSの発生率は低下しているようであるが、それはおそらく前処置レジメンの強度が下がっており、HLAのマッチングが向上しているほか、血液および気管支肺胞標本のPCR検査によって潜在感染の判定が改善しているためであろう。死亡率は50%~70%と報告されている。[ 50 ]しかしながら、これらの推定値は1990年代半ばからのものであり、治療成績は改善している可能性がある。

診断基準には、明らかな感染性微生物が認められない以下の徴候および症状がある:[ 51 ]

- 肺炎。

- X線での非肺葉性浸潤の証拠。

- 肺機能の異常。

感染症を除外するため初期に気管支肺胞洗浄液検査による評価を行うことが重要である。

自己免疫性血球減少症(AIC)

同種HSCT後のAICは、1つの細胞系列(例:自己免疫性溶血性貧血)、2つの細胞系列、または3つの細胞系列に限定することができる。HSCT後の小児患者におけるAICに関する大半のデータは単一施設での経験から報告されており、10~20年間の症例数は20~30人である。[ 54 ][ 55 ][ 56 ]同種HSCT後のAICの発生率は約5%である。AIC発生の危険因子は、年齢が10歳未満であることと、HSCTの適応が良性疾患であることとみられている。少なくとも1つの研究で、血清療法の使用、ドナーソースとしての臍帯血の使用、および重度のGVHDが危険因子として同定されているが、この知見は他の研究では確認されていない。ある研究により、AICを発症した患者は発症しなかった患者と比較して治療成績が悪化することが示された。[ 56 ]しかしながら、他の研究では治療成績の悪化は示されなかった。[ 54 ][ 55 ]

米国国立衛生研究所の慢性GVHDに関する作業部会は、AICを慢性GVHDの非定型的な特徴である可能性がある(ただし、病理学的には異なる場合がある)と認識している。[ 57 ]このグループは、標準化された診断基準を作成し、この合併症のプロスペクティブ研究を提案している。

エプスタイン-バーウイルス(EBV)関連リンパ増殖性疾患

HSCT後、EBV感染の発生率は小児期を通して増加し、感染率は4歳の小児の約40%から10代では80%を超える。以前のEBV感染歴のある患者は、激しく持続性のリンパ球減少に至るHSCT手技(T細胞除去手技、抗胸腺細胞グロブリンまたはアレムツズマブの使用、および程度は低いものの、臍帯血の使用)を受けた場合に、EBV再活性化のリスクが高くなる。[ 60 ][ 61 ][ 62 ]

EBV再活性化の特徴は、PCRで測定される血流中のEBV抗体価における孤立性の上昇から、リンパ腫として発症する著しいリンパ節腫大を伴う侵攻性モノクローナル疾患(リンパ増殖性疾患)までさまざまである。

EBV関連リンパ増殖性疾患の治療

孤立性の血流中のEBV再活性化は、一部の症例で治療を行わなくても免疫機能が改善するにつれて解消しうる。しかしながら、リンパ増殖性疾患にはより積極的な治療が必要である。

EBV関連リンパ増殖性疾患の治療には、免疫抑制剤の減量とシクロホスファミドなどの化学療法薬による治療がある。CD20陽性EBV関連リンパ増殖性疾患およびEBV再活性化は、CD20モノクローナル抗体のリツキシマブによる治療に反応することが示されている。[ 63 ][ 64 ][ 65 ]また、一部の施設により、EBV特異的な細胞傷害性T細胞を治療または予防目的で投与すると、この合併症の治療または予防に効果があることが示されている。[ 66 ][ 67 ][ 68 ]

EBV再活性化のリスク、早期のモニタリング、および積極的な治療に関する知見が向上したことで、この困難な合併症による死亡リスクは有意に低下している。

急性GVHD

GVHDは、レシピエントの組織内に存在するメジャーHLAおよびマイナーHLAの相違を標的としてドナーリンパ球が免疫学的に活性化した結果として発生する。[ 69 ]急性GVHDは通常、移植後最初の3カ月以内に発生するが、ときに完全なドナーキメリズムの達成が遅れる強度減弱および骨髄非破壊的前処置では、遅発型の急性GVHDが報告されている。

典型的に、急性GVHDでは次の3つの症状の少なくとも1つがみられる:

- 皮疹

- 高ビリルビン血症

- 分泌性下痢

急性GVHDは皮膚、肝臓、および消化器症状の重症度で病期分類され、さらにこれら3領域の個別の病期を総合して、予後に有意に関連する全体的なグレードが判定される(表4および表5を参照のこと)。[ 70 ]グレードIIIまたはグレードIVの急性GVHDの患者では、死亡リスクがより高いが、これは総じて、感染症による臓器損傷やときに治療抵抗性となる進行性の急性GVHDが原因である。

表4.急性移植片対宿主病(GVHD)の病期分類a 病期 皮膚 肝臓(ビリルビン) 消化管/腸(排便量/日) 成人 小児 BSA = 体表面積。 a出典:Harris et al.[ 71 ] b他の原因による高ビリルビン血症に対しては、肝病期分類を変更しない。 c消化管の病期分類に関して:体重が50kg超の患者には成人の排便量の値を用いるべきである。排便量に基づく消化管の病期分類については3日間の平均値を用いる。便と尿が混ざっている場合は、便/尿混合物総量の50%を排便量と推定する。 d結腸または直腸生検で消化管のGVHD陽性が示されたものの、排便量が500 mL/日(10mL/kg/日)未満である場合は、消化管の病期は0期とみなす。 e消化管の病期が4期の場合:重度の腹痛という用語は、主治医の判定で(a)オピオイドによる治療が必要であるか、現在使用しているオピオイドの増量が必要な疼痛管理および(b)パフォーマンスステータスに著しく影響する疼痛の両方が認められるものと定義される。 0 GVHDによる発疹がみられない 2 mg/dL未満 500mL未満または3回/日未満 10 mL/kg未満または4回/日未満 1 斑状丘疹型発疹がBSAの25%未満 2~3 mg/dL 500~999mLd または3~4回/日 10~19.9 mL/kgまたは4~6回/日;悪心、嘔吐、または食欲不振が持続し、上部消化管生検の結果が陽性 2 斑状丘疹型発疹がBSAの25%~50% 3.1~6 mg/dL 1,000~1,500mLまたは5~7回/日 20~30 mL/kgまたは7~10回/日 3 斑状丘疹型発疹がBSAの50%超 6.1~15 mg/dL 1,500mL超または7回/日超 30 mL/kg超または10回/日超 4 全身性紅皮症 + BSAの5%を超える水疱形成および落屑 15 mg/dL超 腸閉塞を伴う、または伴わない重度の腹痛e、あるいは(排便量にかかわらず)肉眼的に確認される血便 腸閉塞を伴う、または伴わない重度の腹痛e、あるいは(排便量にかかわらず)肉眼的に確認される血便 表5.全体的な臨床グレード(得られた病期の中で最も高い病期に基づく) . グレード0: すべての臓器について1~4期がみられない グレードI: 皮膚の病期が1~2期、肝臓または腸の病変はみられない グレードII: 皮膚の病期が3期および/または肝臓の病変が1期および/または消化管の病期が1期 グレードIII: 皮膚の病期が0~3期で、肝臓の病期が2~3期および/または消化管の病期が2~3期 グレードIV: 皮膚、肝臓、または消化管の病変が4期 急性GVHDのグレードにより患者の成績に差が生じることから、研究者らは血清バイオマーカー値に基づいて急性GVHDのリスクをより正確に予測することを試みている。成人と小児の両方を対象とした研究では、急性GVHDの発症時に測定された3つのバイオマーカー(腫瘍壊死因子受容体1[TNFR1]、ST2[suppression of tumorigenicity 2]、およびREG3α[regenerating islet-derived 3-alpha])の値を組み合わせて算出するスコアが採用された。著者らは、6カ月死亡率を指標とした低リスク(8%)、中リスク(27%)、および高リスク(46%、P < 0.0001)の集団を定義することに成功した。このバイオマーカースコアは、生存期間の予測に関して臨床病期分類よりも感度および特異度が高かった。[ 72 ]予測アルゴリズムが洗練された結果、2つのバイオマーカー(ST2およびREG3α)の測定のみで高い信頼性で成績を予測できることが示された。さらに、4週間の治療後の予測では、バイオマーカースコアを変更することで生存期間の予測精度をさらに高めることができた。[ 73 ]これらの知見から、急性GVHD患者のバイオマーカーである高リスクまたは低リスクのサブセットを対象とした複数の研究が実施されるようになり、急性GVHD治療のタイミングと強度に関して臨床医に影響を与えている。

急性GVHDの予防および治療

急性GVHDによる罹病および死亡は、予防的に投与する免疫抑制薬、またはex vivoで移植片に含まれる細胞を実際に取り除くか、in vivoで抗リンパ球抗体(抗胸腺細胞グロブリンまたは抗CD52抗体[アレムツズマブ])を用いることによる移植片内のT細胞除去によって減少させることが可能である。

強力なT細胞除去によって急性GVHDを完全に排除すると、一般的に再発が増加し、感染による罹病が増え、EBV関連リンパ増殖性疾患が増加する結果となっている。この結果から、大半のHSCTにおけるGVHDの予防アプローチでは、重度の急性GVHDは予防するが、GVHDのリスクを完全には排除しない程度に十分な免疫抑制を行うことでリスクの均衡を図るように実施される。

T細胞非除去移植片におけるGVHD予防アプローチには以下のものがある:[ 74 ][ 75 ];[ 76 ][証拠レベルC1]

- メトトレキサート間欠投与

- カルシニューリン阻害薬(例:シクロスポリンまたはタクロリムス)

- カルシニューリン阻害薬とメトトレキサートの併用(小児において現在最も一般的に用いられているアプローチ)

- カルシニューリン阻害薬とステロイドまたはミコフェノール酸モフェチルのさまざまな併用

- カルシニューリン阻害薬以外(集中的なT細胞除去、移植後シクロホスファミドなど)カルシニューリン阻害薬以外のアプローチが開発されており、広く用いられるようになっている。

ステロイド抵抗性急性GVHD

重大な急性GVHDが発生した場合の第一選択治療は、一般的にメチルプレドニゾロンである。[ 77 ]この治療に抵抗性を示す急性GVHD患者の予後は不良である。しかしながら、かなりの割合の患者が第二選択治療薬(例:ミコフェノール酸モフェチル、インフリキシマブ、ペントスタチン、シロリムス、または体外フォトフェレーシス)に反応する。[ 78 ]ルキソリチニブは2019年にステロイド抵抗性急性GVHDの12歳以上の小児の治療に対して承認され、治療開始から28日後の全奏効率が55%、完全奏効率が27%であった。これらの薬剤の比較試験は実施されていない。したがって、ステロイド抵抗性GVHDに対する最善の選択肢は特定されていない。[ 79 ][ 80 ]

参考文献- Antin JH: Immune reconstitution: the major barrier to successful stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 11 (2 Suppl 2): 43-5, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Fry TJ, Mackall CL: Immune reconstitution following hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation: challenges for the future. Bone Marrow Transplant 35 (Suppl 1): S53-7, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wingard JR, Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, et al.: Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 29 (16): 2230-9, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bunin N, Small T, Szabolcs P, et al.: NCI, NHLBI/PBMTC first international conference on late effects after pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation: persistent immune deficiency in pediatric transplant survivors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 18 (1): 6-15, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Burik JH, Freifeld AG: Infection in the severely immunocompromised patient. In: Abeloff MD, Armitage JO, Niederhuber JE, et al.: Clinical Oncology. 3rd ed. Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, 2004, pp 941-56.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al.: Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 15 (10): 1143-238, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Infectious Disease Society of America, American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Guidelines for preventing opportunistic infections among hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. MMWR Recomm Rep 49 (RR-10): 1-125, CE1-7, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Levy ER, Musick L, Zinter MS, et al.: Safe and Effective Prophylaxis with Bimonthly Intravenous Pentamidine in the Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Population. Pediatr Infect Dis J 35 (2): 135-41, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hiwarkar P, Amrolia P, Sivaprakasam P, et al.: Brincidofovir is highly efficacious in controlling adenoviremia in pediatric recipients of hematopoietic cell transplant. Blood 129 (14): 2033-2037, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wychera C, Imlay HN, Duke ER, et al.: BK Viremia and Changes in Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate in Children and Young Adults after Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Transplant Cell Ther 29 (3): 187.e1-187.e8, 2023.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, et al.: 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis 58 (3): e44-100, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cordonnier C, Einarsdottir S, Cesaro S, et al.: Vaccination of haemopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: guidelines of the 2017 European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL 7). Lancet Infect Dis 19 (6): e200-e212, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Miller P, Patel SR, Skinner R, et al.: Joint consensus statement on the vaccination of adult and paediatric haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: Prepared on behalf of the British society of blood and marrow transplantation and cellular therapy (BSBMTCT), the Children's cancer and Leukaemia Group (CCLG), and British Infection Association (BIA). J Infect 86 (1): 1-8, 2023.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hill JA, Martens MJ, Young JH, et al.: SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in the first year after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant: a prospective, multicentre, observational study. EClinicalMedicine 59: 101983, 2023.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kumar D, Chen MH, Welsh B, et al.: A randomized, double-blind trial of pneumococcal vaccination in adult allogeneic stem cell transplant donors and recipients. Clin Infect Dis 45 (12): 1576-82, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Reiss U, Cowan M, McMillan A, et al.: Hepatic venoocclusive disease in blood and bone marrow transplantation in children and young adults: incidence, risk factors, and outcome in a cohort of 241 patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 24 (9): 746-50, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cesaro S, Pillon M, Talenti E, et al.: A prospective survey on incidence, risk factors and therapy of hepatic veno-occlusive disease in children after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica 90 (10): 1396-404, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bearman SI: The syndrome of hepatic veno-occlusive disease after marrow transplantation. Blood 85 (11): 3005-20, 1995.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Myers KC, Dandoy C, El-Bietar J, et al.: Veno-occlusive disease of the liver in the absence of elevation in bilirubin in pediatric patients after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (2): 379-81, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Carreras E, Dufour C, Mohty M, et al., eds.: The EBMT Handbook: Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapies. 7th edition. Cham (CH): Springer, 2019. Available online. Last accessed May 7, 2024.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jones RJ, Lee KS, Beschorner WE, et al.: Venoocclusive disease of the liver following bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation 44 (6): 778-83, 1987.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Mohty M, Malard F, Abecassis M, et al.: Revised diagnosis and severity criteria for sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in adult patients: a new classification from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 51 (7): 906-12, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Corbacioglu S, Carreras E, Ansari M, et al.: Diagnosis and severity criteria for sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in pediatric patients: a new classification from the European society for blood and marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 53 (2): 138-145, 2018.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cairo MS, Cooke KR, Lazarus HM, et al.: Modified diagnostic criteria, grading classification and newly elucidated pathophysiology of hepatic SOS/VOD after haematopoietic cell transplantation. Br J Haematol 190 (6): 822-836, 2020.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ruutu T, Eriksson B, Remes K, et al.: Ursodeoxycholic acid for the prevention of hepatic complications in allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood 100 (6): 1977-83, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Myers KC, Lawrence J, Marsh RA, et al.: High-dose methylprednisolone for veno-occlusive disease of the liver in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 19 (3): 500-3, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Richardson PG, Murakami C, Jin Z, et al.: Multi-institutional use of defibrotide in 88 patients after stem cell transplantation with severe veno-occlusive disease and multisystem organ failure: response without significant toxicity in a high-risk population and factors predictive of outcome. Blood 100 (13): 4337-43, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Corbacioglu S, Kernan N, Lehmann L, et al.: Defibrotide for the treatment of hepatic veno-occlusive disease in children after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Expert Rev Hematol 5 (3): 291-302, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Richardson PG, Soiffer RJ, Antin JH, et al.: Defibrotide for the treatment of severe hepatic veno-occlusive disease and multiorgan failure after stem cell transplantation: a multicenter, randomized, dose-finding trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16 (7): 1005-17, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Dignan FL, Wynn RF, Hadzic N, et al.: BCSH/BSBMT guideline: diagnosis and management of veno-occlusive disease (sinusoidal obstruction syndrome) following haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol 163 (4): 444-57, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Strouse C, Richardson P, Prentice G, et al.: Defibrotide for Treatment of Severe Veno-Occlusive Disease in Pediatrics and Adults: An Exploratory Analysis Using Data from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 22 (7): 1306-1312, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Richardson PG, Smith AR, Triplett BM, et al.: Earlier defibrotide initiation post-diagnosis of veno-occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstruction syndrome improves Day +100 survival following haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol 178 (1): 112-118, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Corbacioglu S, Cesaro S, Faraci M, et al.: Defibrotide for prophylaxis of hepatic veno-occlusive disease in paediatric haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation: an open-label, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 379 (9823): 1301-9, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Grupp SA, Corbacioglu S, Kang HJ, et al.: Defibrotide plus best standard of care compared with best standard of care alone for the prevention of sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (HARMONY): a randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol 10 (5): e333-e345, 2023.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ruutu T, Juvonen E, Remberger M, et al.: Improved survival with ursodeoxycholic acid prophylaxis in allogeneic stem cell transplantation: long-term follow-up of a randomized study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 20 (1): 135-8, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bajwa RPS, Mahadeo KM, Taragin BH, et al.: Consensus Report by Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators and Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplantation Consortium Joint Working Committees: Supportive Care Guidelines for Management of Veno-Occlusive Disease in Children and Adolescents, Part 1: Focus on Investigations, Prophylaxis, and Specific Treatment. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 23 (11): 1817-1825, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Mahadeo KM, McArthur J, Adams RH, et al.: Consensus Report by the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators and Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium Joint Working Committees on Supportive Care Guidelines for Management of Veno-Occlusive Disease in Children and Adolescents: Part 2-Focus on Ascites, Fluid and Electrolytes, Renal, and Transfusion Issues. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 23 (12): 2023-2033, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ovchinsky N, Frazier W, Auletta JJ, et al.: Consensus Report by the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators and Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplantation Consortium Joint Working Committees on Supportive Care Guidelines for Management of Veno-Occlusive Disease in Children and Adolescents, Part 3: Focus on Cardiorespiratory Dysfunction, Infections, Liver Dysfunction, and Delirium. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 24 (2): 207-218, 2018.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jodele S, Licht C, Goebel J, et al.: Abnormalities in the alternative pathway of complement in children with hematopoietic stem cell transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Blood 122 (12): 2003-7, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cutler C, Henry NL, Magee C, et al.: Sirolimus and thrombotic microangiopathy after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 11 (7): 551-7, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Schoettler ML, Carreras E, Cho B, et al.: Harmonizing Definitions for Diagnostic Criteria and Prognostic Assessment of Transplantation-Associated Thrombotic Microangiopathy: A Report on Behalf of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, Asia-Pacific Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group, and Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Transplant Cell Ther 29 (3): 151-163, 2023.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jodele S, Dandoy CE, Aguayo-Hiraldo P, et al.: A prospective multi-institutional study of eculizumab to treat high-risk stem cell transplantation-associated TMA. Blood 143 (12): 1112-1123, 2024.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jodele S, Davies SM, Lane A, et al.: Diagnostic and risk criteria for HSCT-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: a study in children and young adults. Blood 124 (4): 645-53, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Dandoy CE, Rotz S, Alonso PB, et al.: A pragmatic multi-institutional approach to understanding transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy after stem cell transplant. Blood Adv 5 (1): 1-11, 2021.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jodele S, Fukuda T, Vinks A, et al.: Eculizumab therapy in children with severe hematopoietic stem cell transplantation-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 20 (4): 518-25, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jodele S, Fukuda T, Mizuno K, et al.: Variable Eculizumab Clearance Requires Pharmacodynamic Monitoring to Optimize Therapy for Thrombotic Microangiopathy after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 22 (2): 307-315, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Schoettler M, Lehmann L, Li A, et al.: Thrombotic Microangiopathy Following Pediatric Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Report of Significant End-Organ Dysfunction in Eculizumab-Treated Survivors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 25 (5): e163-e168, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jodele S, Dandoy CE, Lane A, et al.: Complement blockade for TA-TMA: lessons learned from a large pediatric cohort treated with eculizumab. Blood 135 (13): 1049-1057, 2020.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Svec P, Elfeky R, Galimard JE, et al.: Use of eculizumab in children with allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation associated thrombotic microangiopathy - a multicentre retrospective PDWP and IEWP EBMT study. Bone Marrow Transplant 58 (2): 129-141, 2023.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kantrow SP, Hackman RC, Boeckh M, et al.: Idiopathic pneumonia syndrome: changing spectrum of lung injury after marrow transplantation. Transplantation 63 (8): 1079-86, 1997.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Clark JG, Hansen JA, Hertz MI, et al.: NHLBI workshop summary. Idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after bone marrow transplantation. Am Rev Respir Dis 147 (6 Pt 1): 1601-6, 1993.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Yanik GA, Ho VT, Levine JE, et al.: The impact of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor etanercept on the treatment of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 112 (8): 3073-81, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Yanik GA, Grupp SA, Pulsipher MA, et al.: TNF-receptor inhibitor therapy for the treatment of children with idiopathic pneumonia syndrome. A joint Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium and Children's Oncology Group Study (ASCT0521). Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (1): 67-73, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Szanto CL, Langenhorst J, de Koning C, et al.: Predictors for Autoimmune Cytopenias after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Children. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 26 (1): 114-122, 2020.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Koo J, Giller RH, Quinones R, et al.: Autoimmune cytopenias following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant in pediatric patients: Response to therapy and late effects. Pediatr Blood Cancer 67 (9): e28591, 2020.[PUBMED Abstract]

- O'Brien TA, Eastlund T, Peters C, et al.: Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia complicating haematopoietic cell transplantation in paediatric patients: high incidence and significant mortality in unrelated donor transplants for non-malignant diseases. Br J Haematol 127 (1): 67-75, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cuvelier GDE, Schoettler M, Buxbaum NP, et al.: Toward a Better Understanding of the Atypical Features of Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease: A Report from the 2020 National Institutes of Health Consensus Project Task Force. Transplant Cell Ther 28 (8): 426-445, 2022.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hillier K, Harris EM, Berbert L, et al.: Characteristics and outcomes of autoimmune hemolytic anemia after pediatric allogeneic stem cell transplant. Pediatr Blood Cancer 69 (1): e29410, 2022.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Even-Or E, Schejter YD, NaserEddin A, et al.: Autoimmune Cytopenias Post Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Pediatric Patients With Osteopetrosis and Other Nonmalignant Diseases. Front Immunol 13: 879994, 2022.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Gerritsen EJ, Stam ED, Hermans J, et al.: Risk factors for developing EBV-related B cell lymphoproliferative disorders (BLPD) after non-HLA-identical BMT in children. Bone Marrow Transplant 18 (2): 377-82, 1996.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Shapiro RS, McClain K, Frizzera G, et al.: Epstein-Barr virus associated B cell lymphoproliferative disorders following bone marrow transplantation. Blood 71 (5): 1234-43, 1988.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Brunstein CG, Weisdorf DJ, DeFor T, et al.: Marked increased risk of Epstein-Barr virus-related complications with the addition of antithymocyte globulin to a nonmyeloablative conditioning prior to unrelated umbilical cord blood transplantation. Blood 108 (8): 2874-80, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Blaes AH, Cao Q, Wagner JE, et al.: Monitoring and preemptive rituximab therapy for Epstein-Barr virus reactivation after antithymocyte globulin containing nonmyeloablative conditioning for umbilical cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16 (2): 287-91, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kuehnle I, Huls MH, Liu Z, et al.: CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab) for therapy of Epstein-Barr virus lymphoma after hemopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Blood 95 (4): 1502-5, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Styczynski J, Gil L, Tridello G, et al.: Response to rituximab-based therapy and risk factor analysis in Epstein Barr Virus-related lymphoproliferative disorder after hematopoietic stem cell transplant in children and adults: a study from the Infectious Diseases Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Clin Infect Dis 57 (6): 794-802, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Liu Z, Savoldo B, Huls H, et al.: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes for the prevention and treatment of EBV-associated post-transplant lymphomas. Recent Results Cancer Res 159: 123-33, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bollard CM, Heslop HE: T cells for viral infections after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Blood 127 (26): 3331-40, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Keller MD, Hanley PJ, Chi YY, et al.: Antiviral cellular therapy for enhancing T-cell reconstitution before or after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ACES): a two-arm, open label phase II interventional trial of pediatric patients with risk factor assessment. Nat Commun 15 (1): 3258, 2024.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ferrara JL, Levine JE, Reddy P, et al.: Graft-versus-host disease. Lancet 373 (9674): 1550-61, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al.: 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant 15 (6): 825-8, 1995.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Harris AC, Young R, Devine S, et al.: International, Multicenter Standardization of Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease Clinical Data Collection: A Report from the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 22 (1): 4-10, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Levine JE, Braun TM, Harris AC, et al.: A prognostic score for acute graft-versus-host disease based on biomarkers: a multicentre study. Lancet Haematol 2 (1): e21-9, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Srinagesh HK, Özbek U, Kapoor U, et al.: The MAGIC algorithm probability is a validated response biomarker of treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood Adv 3 (23): 4034-4042, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kanakry CG, O'Donnell PV, Furlong T, et al.: Multi-institutional study of post-transplantation cyclophosphamide as single-agent graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation using myeloablative busulfan and fludarabine conditioning. J Clin Oncol 32 (31): 3497-505, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bertaina A, Merli P, Rutella S, et al.: HLA-haploidentical stem cell transplantation after removal of αβ+ T and B cells in children with nonmalignant disorders. Blood 124 (5): 822-6, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jacoby E, Chen A, Loeb DM, et al.: Single-Agent Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide as Graft-versus-Host Disease Prophylaxis after Human Leukocyte Antigen-Matched Related Bone Marrow Transplantation for Pediatric and Young Adult Patients with Hematologic Malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 22 (1): 112-8, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jacobsohn DA: Acute graft-versus-host disease in children. Bone Marrow Transplant 41 (2): 215-21, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Deeg HJ: How I treat refractory acute GVHD. Blood 109 (10): 4119-26, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jagasia M, Perales MA, Schroeder MA, et al.: Ruxolitinib for the treatment of steroid-refractory acute GVHD (REACH1): a multicenter, open-label phase 2 trial. Blood 135 (20): 1739-1749, 2020.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Laisne L, Neven B, Dalle JH, et al.: Ruxolitinib in children with steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease: A retrospective multicenter study of the pediatric group of SFGM-TC. Pediatr Blood Cancer 67 (9): e28233, 2020.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 慢性移植片対宿主病(GVHD)

-

慢性GVHDは単一臓器系またはいくつかの臓器系に及ぶ症候群で、臨床的特徴は自己免疫疾患に類似している。[ 1 ][ 2 ]慢性GVHDは通常、最初は造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)後2~12カ月の間に発症する。従来は、HSCT後100日を過ぎて発生する症状を慢性GVHDとみなし、HSCTから100日以内に発生する症状は急性GVHDとみなしていた。HSCTに対するアプローチの中には遅発型の急性GVHDにつながるものもあり、また慢性GVHDの診断に至る臨床像がHSCT後100日以内に現れることもあることから、慢性GVHDを構成するそれぞれ明確に異なる病型として、以下の3つが記載されている:

- 古典的慢性GVHD:過去に急性GVHDが発生して消失したことがある患者において、慢性GVHDの診断的またはきわめて特異的な特徴(表6~10を参照のこと)を伴って発生した場合。

- オーバーラップ症候群:GVHDの病態が連続し、急性GVHDの症状が持続している間に慢性GVHDの診断に至る臨床像が認められた場合。

- De novo慢性GVHD:一般に移植から2カ月以上経過後に新たに発生するGVHDで、慢性GVHDの診断的またはきわめて特異的な特徴を伴っているが、急性GVHDの既往やその特徴はみられない場合。

慢性GVHDの臓器障害

慢性GVHDの診断は、臨床的特徴(多形皮膚萎縮症など、診断に至る臨床徴候が1つ以上)か、関連する検査で補完される特有の臨床像(例:シルマテスト陽性でドライアイがみられる)に基づく。[ 3 ]

一般的に侵される組織としては、皮膚、眼、口腔、毛髪、関節、肝臓、消化管などがある。肺、爪、筋肉、泌尿生殖器系、神経系など、他の組織が侵されることもある。表6~10には、慢性GVHDの診断を確定するのに十分な所見の説明を含む、慢性GVHDの臓器別の症状が一覧で示されている。診断確定のために罹患部位の生検が必要となる場合がある。[ 4 ]

一般的な皮膚症状としては、丘疹、局面、または毛包性変化を伴う色素沈着、質感、弾性、および厚さの変化などがある。患者の報告に基づく症状としては、乾燥皮膚、そう痒、可動制限、発疹、びらん、発色や質感の変化などがある。全身性硬皮症は重度の関節性拘縮および衰弱に至る場合がある。関連する脱毛および爪の変化が一般的にみられる。評価すべき他の重要な症状としては、ドライアイおよび萎縮や潰瘍、扁平苔癬などの口の変化が含まれる。また、関節可動域制限に伴う関節硬直、体重減少、悪心、嚥下困難、および下痢にも注意すべきである。

表6.慢性移植片対宿主病(GVHD)による皮膚、爪、頭皮、および体毛の症状a 臓器または部位 診断指標となる特徴 特有の特徴 その他の特徴 一般的な特徴(急性および慢性GVHDの両方にみられる) aAmerican Society for Blood and Marrow TransplantationおよびElsevierから許諾を得て転載:Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Volume 11 (Issue 12), Alexandra H. Filipovich, Daniel Weisdorf, Steven Pavletic, Gerard Socie, John R. Wingard, Stephanie J. Lee, Paul Martin, Jason Chien, Donna Przepiorka, Daniel Couriel, Edward W. Cowen, Patricia Dinndorf, Ann Farrell, Robert Hartzman, Jean Henslee-Downey, David Jacobsohn, George McDonald, Barbara Mittleman, J. Douglas Rizzo, Michael Robinson, Mark Schubert, Kirk Schultz, Howard Shulman, Maria Turner, Georgia Vogelsang, Mary E.D. Flowers, National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. Diagnosis and Staging Working Group Report, Pages 945-956, Copyright 2005.[ 3 ] b慢性GVHDの診断を確定するのに十分である。 c慢性GVHDにみられるが単独で慢性GVHDの診断を確定するには不十分である。 d診断が確定した場合に、慢性GVHDの総体症状の一部として認められる場合がある。 e全例で感染症、薬物の作用、悪性腫瘍、その他の原因を除外する必要がある。 f慢性GVHDの診断には、生検または放射線医学による確認(または眼球の場合はシルマテスト)が必要である。 皮膚 多形皮膚萎縮症 色素脱失 発汗障害 そう痒 扁平苔癬様の特徴 魚鱗癬 紅斑 硬化性の特徴 毛孔性角化症 斑状丘疹型発疹 斑状強皮症様の特徴 低色素沈着 硬化性苔癬様の特徴 色素沈着過剰 爪 異栄養症 爪甲縦線、爪裂症、または脆弱爪 爪甲剥離症 爪翼状片 爪脱落(通常は対称性;ほとんどの爪が罹患)e 頭皮および体毛 頭皮の瘢痕性または非瘢痕性脱毛症の新規発症(化学放射線療法からの回復後) 頭髪減少、典型的に斑状、きめが粗い、または薄ぼんやりした様子(内分泌または他の原因では説明できない) 鱗屑、丘疹鱗屑性病変 早発性白髪 表7.慢性移植片対宿主病(GVHD)による口腔および消化管の症状a 臓器または部位 診断指標となる特徴 特有の特徴 その他の特徴 一般的な特徴(急性および慢性GVHDの両方にみられる) ALT = アラニンアミノトランスフェラーゼ;AST = アスパラギン酸アミノトランスフェラーゼ;ULN = 正常範囲の上限。 a~e表6の定義を参照のこと。 口 苔癬型の特徴 口腔乾燥 歯肉炎 板状角化症 粘液嚢胞 粘膜炎 硬化症による開口制限 偽膜e 紅斑 粘膜萎縮 疼痛 潰瘍e 消化管 食道ウェブ 膵外分泌能の低下 食欲不振 食道の上部~中部3分の1の狭窄e 悪心 嘔吐 下痢 体重減少 成長障害(乳児および小児) 総ビリルビン、アルカリホスファターゼ > 2 × ULNe ALTまたはAST > 2 × ULNe 表8.慢性移植片対宿主病(GVHD)による眼の症状a 臓器または部位 診断指標となる特徴 特有の特徴 その他の特徴 一般的な特徴(急性および慢性GVHDの両方にみられる) a~f表6の定義を参照のこと。 眼球 ドライアイ、ごろごろ感、または眼痛の新規発症f 眼瞼炎(浮腫を伴う眼瞼紅斑) 瘢痕性結膜炎 乾性角結膜炎f 羞明 融合性の点状角膜症 眼窩周囲の色素沈着過剰 表9.慢性移植片対宿主病(GVHD)による生殖器の症状a 臓器または部位 診断指標となる特徴 特有の特徴 その他の特徴 一般的な特徴(急性および慢性GVHDの両方にみられる) a~e表6の定義を参照のこと。 生殖器 扁平苔癬様の特徴 びらんe 膣瘢痕形成または狭窄 亀裂e 潰瘍e 表10.慢性移植片対宿主病(GVHD)による肺、筋肉、筋膜、関節、造血・免疫系、およびその他の症状a 臓器または部位 診断指標となる特徴 特有の特徴 その他の特徴 一般的な特徴(急性および慢性GVHDの両方にみられる) AIHA = 自己免疫性溶血性貧血;BOOP = 器質化肺炎を伴う閉塞性細気管支炎;ITP = 特発性血小板減少性紫斑病;PFT = 肺機能検査。 a~f表6の定義を参照のこと。 肺 肺生検で診断された閉塞性細気管支炎 PFTおよびX線検査で診断された閉塞性細気管支炎f BOOP 筋肉、筋膜、関節 筋膜炎 筋炎または多発性筋炎f 浮腫 筋痙攣 関節痛または関節炎 造血および免疫 血小板減少 好酸球増加症 リンパ球減少 低または高ガンマグロブリン血症 自己抗体(AIHAおよびITP) その他 心嚢水または胸水 腹水 末梢神経障害 ネフローゼ症候群 重症筋無力症 心伝導異常または心筋症 慢性GVHDの危険因子

慢性GVHDは同胞ドナーHSCT後の小児の約15%~30%[ 5 ]、および非血縁ドナーHSCT後の小児の20%~45%に発生する。末梢血幹細胞(PBSC)では慢性GVHDのリスクが高く、臍帯血およびハプロタイプ一致HSCTへの選択されたアプローチではリスクが低い。[ 6 ][ 7 ][ 8 ]

慢性GVHD発症の危険因子としては、以下が含まれる:[ 5 ][ 9 ][ 10 ]

- 患者の年齢(10歳以上)。

- ドナーの種類(非血縁ドナーおよび不一致ドナー)。

- PBSCの使用。

- 急性GVHDの病歴。

- 前処置レジメン(骨髄破壊的および全身照射ベースのレジメン)。

重篤な慢性GVHDを発症する小児では、いくつかの因子が非再発死亡リスクの増加に関連付けられている。HLA不一致移植を受けた小児、PBSC移植を受けた小児、10歳以上の小児、または慢性GVHD診断時の血小板数が100,000/μL未満の小児は、非再発死亡のリスクが高い。

非再発死亡率は、慢性GVHD診断後1年で17%、3年で22%、5年で24%であった。これらの小児の多くは長期の免疫抑制が必要であった。慢性GVHD診断後3年の時点で、小児の約3分の1が再発または再発以外の理由のいずれかで死亡しており、3分の1は免疫抑制を終了し、3分の1は依然として何らかの形で免疫抑制療法を必要としていた。[ 11 ]

古い文献では、慢性GVHDは限局型と全身型のいずれかで記載している。2006年の米国国立衛生研究所(NIH)のConsensus Workshopでは、長期成績をより高い精度で予測するために、慢性GVHDの記載が3つのカテゴリーに拡大された。[ 12 ]NIH悪性度分類における3つのカテゴリーは以下のようになっている:[ 3 ]

- 軽度病変:病変が1つまたは2つの部位のみで、重大な機能障害は認められない(最大の重症度スコアが0~3のスケールで1)。

- 中等度病変:病変がさらに多くの部位(3つ以上)に認められるか、または関連する重症度スコアが高い(いずれかの部位の最大スコアが2)。

- 重度病変:重大な身体機能障害が認められる(いずれかの部位のスコアが3、または肺のスコアが2)。

このように、高リスク患者には、いずれかの部位に重度の病変または複数部位に広範な病変がみられる患者が含まれ、特に以下を認める患者である:

- 症状を伴う肺病変。

- 50%を超える皮膚病変。

- 血小板数が100,000/µL未満。

- パフォーマンススコアが不良(60%未満)。

- 15%を超える体重減少。

- 慢性下痢。

- 発症時に進行中の慢性GVHD。

- 急性GVHDに対してプレドニゾン0.5 mg/kg/日を超える用量のステロイド治療の経験。

ある研究により、軽症および中等症の慢性GVHDを有する小児では重症の慢性GVHDを有する小児よりも長期の無GVHD生存率がはるかに高いことと、治療関連死亡率が低いことが実証された。8年経過時に慢性GVHDが持続している確率は、軽症の慢性GVHDの小児で4%、中等症の慢性GVHDの小児で11%、重症の慢性GVHDの小児で36%であった。[ 13 ]NIHのコンセンサス基準を用いた中央レビューを行った別の大規模臨床試験では、約28%の患者が実際は遅発型の急性GVHDであったのに慢性GVHDありと誤って分類された。さらに、小児の閉塞性細気管支炎のNIHコンセンサス基準を使用する場合、重大な課題があった。[ 14 ]

慢性GVHDの治療

慢性GVHD治療の基本は依然としてステロイドである。しかしながら、カルシニューリン阻害薬の使用など、ステロイドの用量を最低限に抑えるために多くのアプローチが考案されている。[ 15 ]限局型の慢性GVHD患者には、罹患部位に対する局所療法が好ましい。[ 16 ]以下の薬剤が検証されており、一定の成功を収めている:

体外フォトフェレーシスなど、他のアプローチも評価されており、一部の患者でいくらかの有効性が示されている。[ 24 ]

一連の薬剤が小児における慢性GVHDの治療に対して承認されている。

証拠(小児における慢性GVHDの治療):

- イブルチニブは、全身療法が不成功に終わった慢性GVHDの1歳以上の小児患者の治療を適応とする。イブルチニブの有効性は、中等症または重症の慢性GVHDを有する小児および若年成人患者を対象としたオープンラベル多施設共同試験で評価された。この研究では、1ライン以上の治療が不成功に終わった患者47人が対象とされた。年齢の中央値は13歳(範囲、1~19歳)であった。[

25

]

- 25週目までの全奏効率は60%(95%信頼区間[CI]、44%-74%)であった。

- 奏効期間の中央値は5.3カ月(95%CI、2.8-8.8)であった。

- 最初の反応から死亡または慢性GVHDに対する新たな全身療法までの期間の中央値は14.8カ月であった。

- 米国食品医薬品局(FDA)は、1~2ラインの全身療法が不成功に終わった成人および12歳以上の小児における慢性GVHDの治療薬としてルキソリチニブを承認した。この承認は、329人の患者をルキソリチニブまたは利用可能な最善の治療のいずれかにランダムに割り付けた1つの研究に基づいていた。[

22

]

- 全奏効率はルキソリチニブ群で70%(95%CI、63%-77%)、利用可能な最善の治療を選択した群で57%(95%CI、49%-65%)であった。

- キナーゼ阻害薬であるベルモスジルは、2ライン以上の全身療法が不成功に終わった成人患者および12歳以上の小児患者における慢性GVHDの治療薬として承認された。この承認は、複数ラインの治療に抵抗性を示した慢性GVHD患者65人を対象とした研究に基づいていた。[

23

]

- 全奏効率は、ベルモスジル200 mgを1日1回投与された患者で74%(95%、62%-84%)、ベルモスジル200 mgを1日2回投与された患者で77%(95%CI、65%-87%)であった。すべての患者サブグループで高い奏効率が観察された。

- すべての罹患臓器で完全奏効が認められた。

これら3剤の比較研究は実施されていない。したがって、小児の慢性GVHDにおける病型に応じた最善の薬剤はまだ特定されていない。

感染症は臓器機能、QOL、機能に有意な影響を及ぼすことに加えて、慢性GVHD関連死の主要な原因となっている。したがって、慢性GVHDを来した患者には、トリメトプリム/スルファメトキサゾール、ペニシリン、アシクロビルなどの薬剤を用いてニューモシスチス・イロベチイ肺炎、一般的な莢膜を有する微生物の感染症、および水痘に対する予防が全例で行われている。

慢性GVHDの患者では移植関連合併症が死因の70%を占めている。[ 5 ]慢性GVHD患者に対する補助療法および支持療法に関するガイドラインが発表されている。[ 16 ][ 26 ]

参考文献- Shlomchik WD, Lee SJ, Couriel D, et al.: Transplantation's greatest challenges: advances in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 13 (1 Suppl 1): 2-10, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bolaños-Meade J, Vogelsang GB: Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Curr Pharm Des 14 (20): 1974-86, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al.: National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 11 (12): 945-56, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Shulman HM, Kleiner D, Lee SJ, et al.: Histopathologic diagnosis of chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: II. Pathology Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 12 (1): 31-47, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Zecca M, Prete A, Rondelli R, et al.: Chronic graft-versus-host disease in children: incidence, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Blood 100 (4): 1192-200, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Eapen M, Logan BR, Confer DL, et al.: Peripheral blood grafts from unrelated donors are associated with increased acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease without improved survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 13 (12): 1461-8, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Zhang MJ, et al.: Outcomes of transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood and bone marrow in children with acute leukaemia: a comparison study. Lancet 369 (9577): 1947-54, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bertaina A, Zecca M, Buldini B, et al.: Unrelated donor vs HLA-haploidentical α/β T-cell- and B-cell-depleted HSCT in children with acute leukemia. Blood 132 (24): 2594-2607, 2018.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Leung W, Ahn H, Rose SR, et al.: A prospective cohort study of late sequelae of pediatric allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Medicine (Baltimore) 86 (4): 215-24, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Arora M, Klein JP, Weisdorf DJ, et al.: Chronic GVHD risk score: a Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research analysis. Blood 117 (24): 6714-20, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jacobsohn DA, Arora M, Klein JP, et al.: Risk factors associated with increased nonrelapse mortality and with poor overall survival in children with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood 118 (16): 4472-9, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pavletic SZ, Martin P, Lee SJ, et al.: Measuring therapeutic response in chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: IV. Response Criteria Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 12 (3): 252-66, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Inagaki J, Moritake H, Nishikawa T, et al.: Long-Term Morbidity and Mortality in Children with Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease Classified by National Institutes of Health Consensus Criteria after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (11): 1973-80, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cuvelier GDE, Nemecek ER, Wahlstrom JT, et al.: Benefits and challenges with diagnosing chronic and late acute GVHD in children using the NIH consensus criteria. Blood 134 (3): 304-316, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Koc S, Leisenring W, Flowers ME, et al.: Therapy for chronic graft-versus-host disease: a randomized trial comparing cyclosporine plus prednisone versus prednisone alone. Blood 100 (1): 48-51, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Couriel D, Carpenter PA, Cutler C, et al.: Ancillary therapy and supportive care of chronic graft-versus-host disease: national institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic Graft-versus-host disease: V. Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 12 (4): 375-96, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Martin PJ, Storer BE, Rowley SD, et al.: Evaluation of mycophenolate mofetil for initial treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood 113 (21): 5074-82, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jacobsohn DA, Gilman AL, Rademaker A, et al.: Evaluation of pentostatin in corticosteroid-refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease in children: a Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium study. Blood 114 (20): 4354-60, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Jurado M, Vallejo C, Pérez-Simón JA, et al.: Sirolimus as part of immunosuppressive therapy for refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 13 (6): 701-6, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cutler C, Miklos D, Kim HT, et al.: Rituximab for steroid-refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood 108 (2): 756-62, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Miklos D, Cutler CS, Arora M, et al.: Ibrutinib for chronic graft-versus-host disease after failure of prior therapy. Blood 130 (21): 2243-2250, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Zeiser R, Polverelli N, Ram R, et al.: Ruxolitinib for Glucocorticoid-Refractory Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. N Engl J Med 385 (3): 228-238, 2021.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cutler C, Lee SJ, Arai S, et al.: Belumosudil for chronic graft-versus-host disease after 2 or more prior lines of therapy: the ROCKstar Study. Blood 138 (22): 2278-2289, 2021.[PUBMED Abstract]

- González Vicent M, Ramirez M, Sevilla J, et al.: Analysis of clinical outcome and survival in pediatric patients undergoing extracorporeal photopheresis for the treatment of steroid-refractory GVHD. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 32 (8): 589-93, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Carpenter PA, Kang HJ, Yoo KH, et al.: Ibrutinib Treatment of Pediatric Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: Primary Results from the Phase 1/2 iMAGINE Study. Transplant Cell Ther 28 (11): 771.e1-771.e10, 2022.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Carpenter PA, Kitko CL, Elad S, et al.: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: V. The 2014 Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (7): 1167-87, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)後の晩期死亡

-

HSCT後の死亡率は最初の2年が最も高く、ほとんどは再発によるものである。HSCTを受けた悪性腫瘍を有する小児における晩期(移植後2年以上経過後の)死亡の研究によると、2年時に生存していた患者479人のうち約20%に晩期死亡がみられた。同種HSCT群の晩期死亡率は15%(追跡期間の中央値、10.0年[2.0-25.6])で、主な死因は再発(65%)であった。計26%の患者で自家HSCT後の晩期死亡がみられ(追跡期間の中央値、6.7年[2.0-22.2])[ 1 ]、それらの死亡の88%が原発性悪性腫瘍の再発によるものであった。非再発死亡、慢性移植片対宿主病(GVHD)による死亡、および二次悪性腫瘍は、小児では比較的少ない。

別の研究が2回目の同種移植後の晩期死亡の原因についてレビューを行っている。[ 2 ]2回目のHSCT後1年経過時点で生存しており、再発していなかった患者のうち、55%が10年後にも生存していた。この群におけるHSCT後1~10年時点の死因として最も多かったのは再発(死亡の77%)であり、総じて移植後3年以内に生じていた。このコホートにおける10年経過時の非再発死亡の累積発生率は10%であった。この研究では、慢性GVHDが43%の患者で発生し、非再発死亡の最大の原因となった。

1つの研究では、自家HSCT後の小児における晩期死亡率に焦点が置かれた。この研究では、移植を受けた小児の死亡率は、移植後10年以上が経過しても一般集団より高い水準を維持することが示された。しかしながら、15年時点の死亡率は一般集団の死亡率に近づいていた。この研究では、より新しい治療法の時代になると晩期死亡率が低下することも示された(1990年以前、35.1%;1990~1999年、25.6%;2000~2010年、21.8%;P = 0.05)。[ 3 ]

参考文献- Schechter T, Pole JD, Darmawikarta D, et al.: Late mortality after hematopoietic SCT for a childhood malignancy. Bone Marrow Transplant 48 (10): 1291-5, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Duncan CN, Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, et al.: Long-term survival and late effects among one-year survivors of second allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for relapsed acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (1): 151-8, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Holmqvist AS, Chen Y, Wu J, et al.: Late mortality after autologous blood or marrow transplantation in childhood: a Blood or Marrow Transplant Survivor Study-2 report. Blood 131 (24): 2720-2729, 2018.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 小児における造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)後の晩期障害

-

HSCTを受けた小児および成人の生存者を対象とした諸研究のデータから、治療に関連した曝露が生存およびQOLに有意な影響を及ぼすことが示されている。[ 1 ]HSCTを受けた2年後に生存していた患者を対象とした研究では、生存者の早期死亡のリスクが、米国一般集団の年齢および性別でマッチングした対照と比較して9.9倍高かった。[ 2 ]別の多施設共同研究では、小児期にHSCTを受けた成人生存者の半数以上がグレード3または4の慢性的な健康障害を有していることが示された。同胞と比較した生存者のオッズ比(OR)は15.1であった。[ 3 ]

HSCT後の晩期障害の研究における方法論的課題

HSCTを受けた患者の主な死因は原発腫瘍の再発であるが、HSCTを受けた患者の多くが移植片対宿主病(GVHD)に関連した感染症、二次悪性腫瘍、心疾患、または肺疾患により死亡している。[ 2 ][ 4 ][ 5 ][ 6 ]さらに他の諸研究により、HSCT生存者の最大40%が重度の事象、身体障害につながる事象、または死に至る事象を経験するか、初回または過去のがん治療に関連した有害事象のために死亡することも明らかにされた。[ 7 ][ 8 ]

そうした障害の発生率や重症度を抑制することを目指した研究を開始する前に、それらの合併症の発生に至る要因を理解しておくことが重要である:

- 移植前の治療:移植前の治療は重要な役割を果たすが、HSCT前の治療に関連した有意な曝露について詳細に検討した研究は多くない。[ 9 ]

- 前処置レジメン:全身照射や大量化学療法を含む移植の前処置レジメン自体はしばしば研究されているが、この集中的な治療は晩期障害の潜在的な原因で満たされた長期にわたる治療の一部分に過ぎない。

- 同種性:同種性の影響(GVHD、自己免疫、慢性炎症、ときに検出されない臓器損傷に至る主要およびマイナーHLAの差異)もこれらの晩期障害 の発生に寄与する。

- 化学療法薬以外の薬剤への長期曝露:移植を受ける患者には、有意な毒性を長期間伴う免疫抑制薬(例;高血圧や腎障害を引き起こすことがあるシクロスポリンまたはタクロリムス)が投与されることがある。さらに、臓器障害と関連している可能性がある支持療法薬または抗菌薬(例:リポソーム化アムホテリシンB)を長期にわたって投与することがルーチンとなっている。晩期障害のリスクを評価する際には、これらの薬剤を考慮すべきである。

化学療法による特異的な臓器損傷への罹病性やドナーおよびレシピエントにおける遺伝的差異に基づくGVHDのリスクには個人差がある。[ 9 ][ 10 ][ 11 ]

心血管系の晩期障害

心機能不全はHSCT以外の設定では広く研究されているが、小児におけるHSCT後のうっ血性心不全の発生率および予測因子についてはほとんど不明である。HSCTに特有の潜在的に心毒性を有する曝露には以下のものがある:[ 12 ]

- 大量化学療法による前処置、特にシクロホスファミド

- 全身照射

一部には、全身照射による被曝や同種HSCT後の長期の免疫抑制療法への曝露の結果、あるいは他の健康状態(例:甲状腺機能低下または成長ホルモン欠乏)に関係して、HSCT生存者は高血圧や糖尿病など心血管系の危険因子となる疾患を発症するリスクが高い。[ 8 ][ 12 ]同種HSCT後2年以上生存している小児患者661人を対象とした研究では、最近の検査時に52%の患者が肥満または過体重であり、18%の患者が脂質異常症(HSCT前のアントラサイクリン系薬剤または頭蓋や胸部照射に関連)であり、7%の患者が糖尿病と診断されていた。[ 13 ]

心血管系の転帰の割合が、1985年から2006年にシアトルで治療された1,500人近い(2年以上生存している)移植生存者において調査された。生存者と集団ベースの比較群は、年齢、年、および性別でマッチングされた。[ 14 ]生存者では心血管系の死亡の割合が高かった(調整後発生率差、1,000人年当たり3.6[95%信頼区間、1.7-5.5])。また、生存者では以下の累積発生率が高かった:

- 虚血性心疾患

- 心筋症/心不全

- 脳卒中

- 血管疾患

- 不整脈

生存者ではまた、より重篤な心血管疾患の発生リスクを増大させる関連疾患(すなわち、高血圧、腎疾患、異脂肪血症、および糖尿病)の累積発生率が高かった。[ 14 ]

さらに、心機能とHSCT前の化学療法や放射線療法への曝露がHSCT後の心機能に有意な影響を及ぼすことが示されている。HSCT後の長期の問題について患者を評価する場合、HSCT前のアントラサイクリンの用量および胸部放射線照射の線量を考慮することが重要である。[ 15 ]このアプローチを検証するにはより特異的な研究が必要であるが、現在の証拠によれば、HSCT後の晩期に発生する心血管系合併症のリスクは、主としてHSCT前の治療上の曝露によるものであり、前処置に関連する曝露またはGVHDによる追加のリスクはほとんど認められないことが示唆されている。[ 16 ][ 17 ]

詳しい情報については、「小児がんに対する治療の晩期障害」の心血管系の晩期障害のセクションを参照のこと。

神経認知的晩期障害

多くの研究からHSCT後の正常な神経発達が報告されており、認知機能低下の証拠は認められていない。[ 18 ][ 19 ][ 20 ][ 21 ][ 22 ][ 23 ][ 24 ][ 25 ]

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospitalの研究チームによる現時点で最大規模の縦断的コホートの検討から、移植後5年間にわたる追跡期間中の全般的な認知機能と学業達成度について顕著な安定性が報告されている。[ 21 ][ 22 ][ 23 ]この研究グループにより、非血縁ドナー移植を受けた患者が全身照射を受けた場合やGVHDを発症した場合に転帰がより不良であったことが報告された。しかしながら、社会経済的地位が認知機能に及ぼすはるかに大きな影響と比較すると、これらが転帰に及ぼす影響は小さかった。[ 22 ]発表されている研究の大半で同様の転帰が報告されている。HSCT後2年間にわたってプロスペクティブに監視された患者47人のコホートにおいて、正常な認知機能および学力達成度が報告された。[ 25 ]認知機能の安定は、移植前からHSCT後2年経過時まで監視された大規模コホートにおいても認められた。[ 20 ]比較的小規模の研究により、HSCT生存者において時間の経過とともに同様に機能が正常化し、低下が認められなくなったことが報告された。[ 18 ]HSCT生存者は、知覚的体制化の測定については同胞よりも生存者の方が成績が良かったことを除いて認知機能および学力において同胞と差がなかった。[ 19 ]現在までの知見によれば、HSCTが生存者に及ぼす晩期の認知障害および学力に関する障害のリスクは最小限から低いものであると思われる。

しかしながら、いくつかの研究でHSCT後の認知機能におけるある程度の低下が報告されている。[ 26 ][ 27 ][ 28 ][ 29 ][ 30 ][ 31 ][ 32 ]これらの研究では、非常に幼い小児の割合が高いサンプルが含まれている傾向があった。ある研究では、HSCT後1年経過時点でコホートのIQが有意に低かったことが報告され、その問題はHSCT後3年経過時点でも認められた。[ 27 ][ 28 ]同様に、スウェーデンの研究では、全身照射を併用して移植を受けた非常に幼い小児で、視覚空間領域および実行機能における障害が報告されている。[ 30 ][ 31 ]St. Jude Children's Research Hospitalの別の研究では、3歳未満の小児すべてに移植後1年の時点でIQの低下が認められた一方で、前処置中に全身照射を施行しなかった患児は後に回復したことが報告された。全身照射を受けた患児は全身照射を受けなかった患児よりも5年時点のIQが有意に低かった(P = 0.05)。[ 32 ]

詳しい情報については、「小児がんに対する治療の晩期障害」の造血幹細胞移植(HSCT)のセクションを参照のこと。

消化器系の晩期障害

消化管、胆管、および膵臓の機能不全

消化管の晩期障害のほとんどは、遅延性の急性GVHDおよび慢性GVHDに関係している(表11を参照のこと)。詳しい情報については、「小児がんに対する治療の晩期障害」の肝胆道系のセクションを参照のこと。

GVHDが制御され、耐性が得られるにつれて、ほとんどの症状は消退する。肝胆道の主な懸念としては、移植前または移植中に感染したウイルス性肝炎の影響、胆石疾患、および局所性肝病変が挙げられる。[ 33 ]こうした疾患と肝細胞障害で現れるGVHDとを区別するために、ウイルス血清学的検査およびポリメラーゼ連鎖反応検査を実施すべきである。[ 34 ]

表11.長期移植生存者における消化管、肝胆道、および膵臓の異常の原因a 問題の領域 一般的な原因 より頻度が低い原因 ALT = アラニントランスアミナーゼ;AP = アルカリホスファターゼ;CMV = サイトメガロウイルス;GGT = γグルタミルトランスペプチターゼ;GVHD = 移植片対宿主病;HSV = 単純ヘルペスウイルス;Mg++ = マグネシウム;VZV = 水痘帯状疱疹ウイルス。 aAmerican Society for Blood and Marrow TransplantationおよびElsevierから許諾を得て転載:Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Volume 17 (Issue 11), Michael L. Nieder, George B. McDonald, Aiko Kida, Sangeeta Hingorani, Saro H. Armenian, Kenneth R. Cooke, Michael A. Pulsipher , K. Scott Baker, National Cancer Institute-National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute/Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium First International Consensus Conference on Late Effects After Pediatric Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: Long-Term Organ Damage and Dysfunction, Pages 1573-1584, Copyright 2011.[ 34 ] 食道症状:胸やけ、嚥下困難、嚥下痛 [ 35 ][ 36 ][ 37 ][ 38 ][ 39 ][ 40 ] 口腔の慢性GVHD(粘膜の変化、歯列不正、口腔乾燥) 食道の慢性GVHD(食道ウェブ、食道輪、粘膜下線維化および狭窄、無蠕動) 胃液の逆流 下咽頭の運動障害(重症筋無力症、輪状咽頭の協調不全) 扁平上皮がん > 腺がん 錠剤誘発性食道炎 感染症(真菌性、ウイルス性) 上部消化管症状:食欲不振、悪心、嘔吐 [ 41 ][ 42 ][ 43 ][ 44 ][ 45 ] 遅延性の急性消化管GVHD 続発性副腎機能不全 潜伏感染の活性化(CMV、HSV、VZV) 感染(腸管ウイルス、ジアルジア属、クリプトスポリジウム属、Haemophilus pylori) 医薬品の有害作用 消化管運動障害 小腸および大腸症状:下痢および腹痛 [ 46 ][ 47 ] 遷延性の急性消化管GVHD 感染(腸管ウイルス、細菌、寄生虫) 潜伏していたCMV、VZVの活性化 膵機能不全 薬剤(ミコフェノール酸モフェチル、Mg2+、抗菌薬) Clostridium difficile結腸炎 腸壁へのコラーゲン沈着(GVHD) まれ:炎症性腸疾患、スプルー[ 47 ];胆汁酸塩吸収不良;二糖類吸収不良 肝臓の問題 [ 33 ][ 48 ][ 49 ][ 50 ][ 51 ][ 52 ][ 53 ][ 54 ][ 55 ][ 56 ][ 57 ] 胆汁うっ滞型肝障害を伴うGVHD 肝炎を伴うGVHD 慢性ウイルス性肝炎(B型およびC型) VZVまたはHSVによる肝炎 肝硬変 真菌性膿瘍 局所性結節性過形成 結節性再生性過形成 血清肝酵素値の非特異的上昇(AP、ALT、GGT) 胆道閉塞 薬剤性肝障害 胆汁および膵臓の問題[ 58 ][ 59 ][ 60 ][ 61 ] 胆嚢炎 膵萎縮/膵機能不全 総胆管結石/胆泥 膵炎/浮腫(膵石または胆泥に関連) 胆嚢泥(色素石灰石) 膵炎(タクロリムスに関連) 胆石 鉄過剰症

HSCTの施行後には、ほぼ全例で鉄過剰症がみられるが、特にHSCT前からあった輸血依存を伴う病態(例:サラセミア、骨髄不全症候群)または骨髄毒性のある化学療法後からHSCTまでに輸血を必要とする疾患(例:急性白血病)に対して行われる場合に顕著となる。GVHDなどの炎症性疾患も消化管での鉄吸収の増加につながる。HSCTと関係なく鉄過剰症を来す病態は、心機能不全、内分泌障害(例:下垂体機能不全、甲状腺機能低下症)、糖尿病、神経認知障害、および二次悪性腫瘍に至ることがある。[ 34 ]

鉄過剰症がHSCT後の病態に及ぼす影響は十分に研究されていない。しかしながら、サラセミアに対するHSCT後には鉄の血中濃度を低下させることで、心機能が改善することが示されている。[ 62 ]

鉄除去療法(HSCT後の瀉血や鉄キレートなど)を支持するデータでは、この治療を行うべき具体的な検査値は同定されていない。ただし、フェリチンが高値であるか肝生検またはT2強調MRIで有意な鉄過剰の所見が認められる場合は[ 63 ]、鉄除去療法で対処すべきである。[ 64 ]

内分泌系の晩期障害

甲状腺機能障害

諸研究により、骨髄破壊的HSCT後の小児における甲状腺機能障害の割合はさまざまであることが示されており、比較的大規模のシリーズでは約30%の平均発生率が報告されている。[ 65 ][ 66 ][ 67 ][ 68 ][ 69 ][ 70 ][ 71 ][ 72 ][ 73 ][ 74 ][ 75 ]成人における低い発生率(平均で15%)およびHSCTを受けた10歳未満の小児における発生率の顕著な増加から、発達中の甲状腺はより損傷を受けやすいことが示唆されている。[ 65 ][ 67 ][ 71 ][ 75 ]

移植前の甲状腺への局所放射線療法は、ホジキンリンパ腫患者における高率の甲状腺機能障害の一因となっている。[ 65 ]初期の研究では、全身照射の高線量単回照射後に非常に高い割合の甲状腺機能障害が示されたが[ 76 ]、従来の分割照射による全身照射/シクロホスファミドはブスルファン/シクロホスファミドと比較して、同程度の割合の甲状腺機能障害が示されたことから、甲状腺損傷における大量化学療法の役割が示唆されている。[ 68 ][ 69 ][ 70 ]注目すべきことに、ある大規模研究では、全身照射またはブスルファンによる治療を受けた患者では甲状腺機能障害の発生率が同程度に高かったのに対し、トレオスルファンの投与または化学療法ベースの強度減弱レジメンによる治療を受けた患者では甲状腺疾患の発生率が低かったことが示された。[ 75 ]詳しい情報については、「小児がんに対する治療の晩期障害」の移植後の甲状腺機能障害のセクションを参照のこと。

甲状腺機能障害の発生率は、3剤によるGVHD予防よりも単剤による予防で高い。[ 77 ]非血縁ドナーHSCT後の方が血縁ドナーHSCT後よりも甲状腺機能障害の発生率(36% vs 9%)が高いことから[ 66 ]、甲状腺機能障害の原因として同種免疫反応による傷害の関与が示唆されている。[ 70 ][ 78 ]

成長障害

成長障害は一般的に多因子性である。HSCTを受けた幼児が成人に期待される身長に到達できない場合の原因となる因子としては以下のものがある:

- 成長ホルモン濃度の低下

- 甲状腺機能障害

- 思春期の性ホルモン産生の崩壊

- ステロイド療法

- 栄養不良状態

成長障害の発生率は、年齢、危険因子、および発生率を報告したグループにより用いられた成長障害の定義によって20%~80%とばらつきがある。[ 72 ][ 73 ][ 79 ][ 80 ][ 81 ][ 82 ]危険因子としては、以下が挙げられる:[ 68 ][ 69 ][ 80 ][ 83 ]

- 全身照射

- 頭蓋照射

- 若年者

- 急性リンパ芽球性白血病に対するHSCT。

- 思春期成長スパート中にHSCTを受けたこと。[ 84 ]

HSCT時に10歳未満の患者は成長障害のリスクが最も高いが、成長ホルモン補充療法に対する反応も最も良好である。成長障害の徴候を示す患者を早期にスクリーニングして内分泌専門医に紹介することで、若年での身長の有意な回復が得られる可能性がある。[ 82 ]

詳しい情報については、「小児がんに対する治療の晩期障害」の成長ホルモン欠乏症のセクションを参照のこと。

身体組成の異常およびメタボリックシンドローム

HSCT後の成人生存者では、一般集団と比較して心血管系に関係した早期死亡のリスクが2.3倍高い。[ 85 ][ 86 ]心血管系リスクとその後の死亡の正確な病因はほとんど明らかになっていない。しかしながら、HSCTの結果としてメタボリックシンドローム(中心性肥満、インスリン抵抗性、グルコース不耐症、異脂肪血症、および高血圧といった一連の病態)、特にインスリン抵抗性の発症が示唆されている。[ 87 ][ 88 ][ 89 ]

従来の治療法による白血病生存者とHSCTを受けた生存者を比較した研究によると、移植生存者はメタボリックシンドロームを発症するか、中心性肥満、高血圧、インスリン抵抗性、異脂肪血症など複数の有害な心臓性の危険因子を有する可能性が有意に高い。[ 34 ][ 90 ][ 91 ]経時的な懸念として、HSCT後にメタボリックシンドロームを発症する生存者では、心血管系関係の有意な事象や心血管系関係の原因による早期死亡の発生リスクが比較的高い。

詳しい情報については、「小児がんに対する治療の晩期障害」のメタボリックシンドロームのセクションを参照のこと。

サルコペニア肥満

一般集団において肥満と糖尿病および心血管系疾患のリスクとの関連については十分に確立されているが、HSCT後の長期生存者では肥満指数(BMI)により確認される肥満はまれである。[ 91 ]しかしながら、HSCT生存者ではBMI正常でも身体組成に有意な変化が起こり、総脂肪量の増加と除脂肪体重の減少が同時にみられる。この所見はサルコペニア肥満と呼ばれ、筋細胞のインスリン受容体の喪失と脂肪細胞のインスリン受容体の増加が起こる;後者はインスリンと結合してグルコースを除去する効率が低く、最終的にはインスリン抵抗性に寄与する。[ 92 ][ 93 ][ 94 ]

小児および若年成人生存者119人と健康な同胞対照81人を対象とした予備的データにより、HSCT生存者は同胞と比較して有意に低体重であったことが示されたが、BMIおよびウエスト周囲には差が認められなかった。[ 95 ]HSCT生存者では、対照より体脂肪率が有意に高く、除脂肪体重が有意に低かった。HSCT生存者では、対照よりインスリン抵抗性が有意に強かったほか、総コレステロール、低比重リポ蛋白コレステロール、およびトリグリセリドの高値など、他の心血管系危険因子の頻度も高かった。これらの差は移植の前処置レジメンの一環として全身照射を受けていた患者にのみ認められた。

筋骨格系の晩期障害

骨密度の低下

小児におけるHSCT後の骨密度低下を扱った研究はほとんどない。[ 96 ][ 97 ][ 98 ][ 99 ][ 100 ][ 101 ][ 102 ]有意な割合の小児が全身の骨密度低下を経験したか、腰椎骨密度のZスコアで骨減少(18%~33%)または骨粗鬆症(6%~21%)が認められた。一般的な危険因子(女性、運動不足、栄養不良、白人またはアジア系、家族歴、全身照射、頭蓋脊髄照射、コルチコステロイド療法、GVHD、シクロスポリン、内分泌機能低下症[例:成長ホルモン欠乏症、性腺機能低下症])が報告されているが、多変量解析で各因子の相対的な重要度を検証するには、報告された集団の大半は患者数が不足している。[ 103 ][ 104 ][ 105 ][ 106 ][ 107 ][ 108 ][ 109 ][ 110 ][ 111 ][ 112 ][ 113 ]

成人を対象とした一部の研究では、HSCT後の骨密度低下は経時的に改善することが示されている。[ 101 ][ 114 ][ 115 ]しかしながら、この知見は小児ではまだ示されていない。

小児に対する治療では一般的に多因子的アプローチが用いられ、ビタミンDおよびカルシウム補給、コルチコステロイド療法の最小化、荷重負荷運動への参加、および他の内分泌異常の軽減などがある。この条件で小児におけるビスホスホネート療法の役割は不明である。

詳しい情報については、「小児がんに対する治療の晩期障害」の骨粗鬆症および骨折のセクションを参照のこと。

骨壊死

HSCT後の小児における骨壊死の発生率は1%~14%と報告されている。しかしながら、これらの研究はレトロスペクティブ研究であり、患者は疾患経過の初期に無症状の場合があるため、実際の発生率は過小評価されていた。[ 116 ][ 117 ][ 118 ]2つのプロスペクティブ研究では、可能性のある標的の関節にルーチンでMRIスクリーニングを実施したところ、30%~44%の発生率が示された。[ 100 ][ 119 ]骨壊死は一般的にHSCT後3年以内に発生し、発症までの期間の中央値は約1年である。最も一般的な部位は、膝関節(30%~40%)、股関節(19%~24%)、および肩関節(9%)である。ほとんど患者が2ヵ所以上の関節で骨壊死を経験する。[ 76 ][ 116 ][ 120 ][ 121 ]

あるプロスペクティブ研究では、多変量解析で同定された危険因子として、年齢(10歳以上の小児では顕著に増加;OR、7.4)と移植時点での骨壊死が報告された。コルチコステロイドへの曝露など、HSCT前の因子が患者のリスク判定で非常に重要であるという点に注意する必要がある。この研究では、骨壊死を発症した小児44人中14人がHSCT前にこの疾患に罹患していた。[ 119 ]160人の症例と478人の対照小児を対象にしたCenter for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research(CIBMTR)のレトロスペクティブ・ネステッドケースコントロール研究により、骨壊死発症の危険因子として比較的高い年齢(5歳超)、女児、および慢性GVHDの存在が示唆された。[ 122 ]

治療は一般に、コルチコステロイド療法の最小化と外科的関節置換術で構成されている。ほとんどの患者は症状が現れるまで診断されない。骨壊死病変を有する患者44人を対象として年1回のMRIをルーチンに施行した研究では、4人で完全な消退が、2人で複数あった罹患関節の1つで消退がみられた。[ 119 ]時間の経過とともに一部の病変が治癒するという観察から、無症状の病変に対する外科的管理には注意が必要であることが示唆されている。

詳しい情報については、「小児がんに対する治療の晩期障害」の骨壊死のセクションを参照のこと。

生殖器系の晩期障害

思春期発達

HSCTの施行後には思春期発達の遅れ、欠如、停止がよくみられる。2つの研究により、シクロホスファミド単剤の投与を受けた女児の16%、ブスルファン/シクロホスファミドの投与を受けた女児の72%、分割で全身照射を受けた女児の57%で思春期の遅発または欠如がみられたことが示された。男性では、シクロホスファミド単独の投与を受けた男児の14%、ブスルファン/シクロホスファミドの投与を受けた男児の48%、全身照射を受けた男児の58%において、思春期発達の停止または欠如が示された。[ 74 ][ 123 ]精巣への24 Gy超の放射線を受けた男児は無精子症を発症し、テストステロン産生不全も経験したため、二次性徴を誘導するための補充が必要であった。[ 124 ]

妊孕性

女性

移植前および移植時のシクロホスファミドへの曝露は、薬剤が妊孕性に影響を及ぼす事例として最もよく研究されている。30歳未満の思春期後女性は最大20g/m2のシクロホスファミドに耐えられ、卵巣機能を維持する。思春期前の女性は25g/m2~30g/m2もの用量に耐えられる。移植前のシクロホスファミドや他の薬剤への曝露による追加的な影響を特異的に算出する試みはなされていないが、こうした曝露と移植に関連した化学療法および放射線療法が合わさることで、骨髄破壊的HSCTを受ける女性の65%~84%が卵巣機能不全を来している。[ 125 ][ 126 ][ 127 ][ 128 ]前処置レジメンとしてシクロホスファミド、ブスルファン、および全身照射を用いることには、卵巣機能悪化との関連が認められる。HSCT時の年齢が若い方が、初経および排卵の可能性が高くなる。[ 129 ][ 130 ]詳しい情報については、「小児がんに対する治療の晩期障害」のHSCT後の卵巣機能のセクションを参照のこと。

個々の患者が妊娠を試みているかどうかを示したデータはめったにないため、妊娠に関する研究は容易ではない。それでも、骨髄破壊的移植を受けた小児および成人生存者の妊娠について検討した大規模研究では、患者708人中32人(4.5%)で妊娠が確認された。[ 125 ]妊娠を試みた患者のうち、シクロホスファミド単剤の投与(総用量6.7g/m2、移植前の曝露はなし)を受けた患者が最も妊娠する可能性が高かった(103人中56人、54%)一方で、ブスルファン/シクロホスファミドによる骨髄破壊的前処置を受けた患者(73人中0人、0%)と全身照射を受けた患者(532人中7人、1.3%)では、妊娠率がはるかに低かった。

男性

生殖能のある精子を産生する能力は、高用量の化学療法および各種の化学療法への曝露に伴って低下する。大半の男性は、用量300 mg/kgのシクロホスファミド投与で無精子症になる。[ 131 ]HSCT後には、48%~85%の男性が性腺機能不全を経験する。[ 125 ][ 131 ][ 132 ]ある研究では、シクロホスファミドを投与された男性のパートナーが妊娠を達成できたのは、妊娠を試みた場合の24%のみであったのに対し、ブスルファン/シクロホスファミドでは6.5%、全身照射では1.3%であった。[ 125 ]詳しい情報については、「小児がんに対する治療の晩期障害」のHSCT後の精巣機能のセクションを参照のこと。

毒性軽減、強度減弱、または骨髄非破壊的レジメンの効果

毒性を軽減した一部の化学療法レジメンによる用量効果および性腺毒性低下に関する明確な証拠に基づくと、強度減弱、毒性軽減、または骨髄非破壊的レジメンを使用することでHSCT後も妊孕性を温存できる可能性が高まると考えられる。それらのレジメンの使用は比較的新しく、その大半が比較的高齢または病状の悪い患者に対象が限定されているため、大半の報告が単一症例のものである。レジストリー研究から、これらの前処置後の妊娠例が報告されるようになっている。[ 128 ]さらに、ある単一施設研究では、ブスルファン/シクロホスファミドの骨髄破壊的レジメンとフルダラビン/メルファランの強度減弱レジメンが比較された。[ 133 ][証拠レベルC1]ブスルファン/シクロホスファミド群では自然な思春期発来がみられた患者の割合が女児で56%、男児で89%であったのに対し、フルダラビン/メルファラン群では女児の90%とすべての男児で自然な思春期発来がみられた(P = 0.012)。ホルモン補充療法が必要になった女児の割合は、ブスルファン/シクロホスファミド群(61%)の方がフルダラビン/メルファラン群(10.5%)より有意に高かった(P = 0.012)。男児では、2つの前処置群間で卵胞刺激ホルモン(FSH)値上昇までの期間に差が認められなかった(中央値はフルダラビン/メルファラン群で4年 vs ブスルファン/シクロホスファミド群で6年)。2つのレジメンが精巣機能に及ぼす影響は同程度であるが、卵巣機能は強度減弱前処置でHSCTを受けた女児でより良好に温存されるようである。

別の研究では、1回のHSCT後に1年以上生存し、トレオスルファンベースのレジメン(トレオスルファン;毒性軽減)、フルダラビン/メルファラン(Flu/Mel;強度減弱)、またはブスルファン/シクロホスファミド(Bu/Cy;骨髄破壊的)による前処置を受けた小児121人を対象として、抗ミュラー管ホルモン(AMH)およびインヒビンBの血清中濃度が比較された。HSCT時の平均年齢は3.6歳で、追跡調査時の平均年齢は11.8歳であった。平均追跡期間は9.9年であった。AMHの標準偏差スコア(SDS)の平均値は、Bu/Cy(-1.543)よりトレオスルファン(-1.047)およびFlu/Mel(-1.255)の方が有意に高く、Bu/CyよりもトレオスルファンおよびFlu/Melの方が卵巣予備能の障害が少ないことが示唆された。血清AMH濃度の平均値は、トレオスルファン(>1.0μg/L)の方がFlu/MelまたはBu/Cyより有意に良好であった。男性では、インヒビンBのSDSの平均値は、Flu/Mel(-2.53)または一部のBu/Cy(-1.23)よりトレオスルファン(-0.506)の方が有意に高かった。Flu/MelまたはBu/Cyレジメンと比較して、トレオスルファンベースのレジメンの方が男女とも性腺予備能の予後が良好と結論された。[ 134 ]同様の報告では、トレオスルファンによる前処置を受けた小児において、ブスルファンおよび全身照射ベースのアプローチと比較して思春期到達度およびライディッヒ細胞機能が良好であったことが示された。[ 135 ]

別の研究では、Bu/Cyおよびシクロホスファミド/全身照射による骨髄破壊的前処置を受けた患者とフルダラビン/メルファラン/アレムツズマブによる強度減弱前処置を受けた患者との間で、性腺機能マーカーが比較された。[ 136 ]

- 強度減弱前処置を受けた女性患者は原発性卵巣機能不全を発症する可能性が低く、このことはFSHの低値(P = 0.02)とエストラジオールの低値(P = 0.01)または黄体形成ホルモンの高値(P = 0.09)により実証された。

- 強度減弱前処置群(75%)および骨髄破壊的前処置群(93%)の女性の大半でAMH濃度が低く、卵巣予備能が低いかないことが示唆された。

- 男性では、インヒビンB値の中央値は強度減弱前処置後の方が高かったが、2群間に有意差は認められなかった。強度減弱小前処置を受けた男性11人中10人(91%)と骨髄破壊的前処置を受けた男性10人の全員(100%)に無精子症または乏精子症が認められた。HSCTから精液検査までの経過期間の中央値は3.7年(範囲、1.3~12.2年)であった。

- これらの患者の多くは、解析で考慮されなかった性腺毒性のある薬剤にHSCT前に曝露していた。

- この研究は小規模なものであったが、フルダラビン/メルファラン/アレムツズマブなどの強度減弱前処置後の不妊症リスクはかなり高い可能性があることを示す証拠が得られた。

呼吸器系の晩期障害

慢性肺機能不全

HSCT後にみられる慢性肺機能不全には、以下に示す2つの型がある:[ 137 ][ 138 ][ 139 ][ 140 ][ 141 ][ 142 ]

- 閉塞性肺疾患

- 拘束性肺疾患

2つの型の肺毒性作用の発生率は、ドナー細胞のソース、HSCT後の期間、適用された定義、慢性GVHDの有無に応じて、10%~40%の範囲をとる。どちらの病態でも、間質腔(拘束性肺疾患)または細気管支周囲のスペース(閉塞性肺疾患)のいずれかにおけるコラーゲン沈着および線維化の発生がその病理の根底にあると考えられる。[ 143 ]

閉塞性肺疾患

同種HSCT後の閉塞性肺疾患の中で最も一般的な病型は閉塞性細気管支炎である。[ 139 ][ 142 ][ 144 ][ 145 ]これは細気管支閉塞、線維化、および進行性の閉塞性肺疾患を引き起こす炎症性の病態である。[ 137 ]

歴史的に、閉塞性細気管支炎という用語は肺の慢性GVHDを記載するために用いられていたが、この病態はHSCTの6~20カ月後に発症する。肺機能検査では、努力肺活量(FVC)の全般的維持、一秒量(FEV1)の低下、およびこれに伴ったFEV1/FVC比の低下がみられる閉塞性肺疾患が示されるほか、一酸化炭素の肺拡散能(DLCO)の有意な低下が認められる場合もある。

閉塞性細気管支炎の危険因子としては以下のものがある:[ 137 ][ 144 ]

- 移植前のFEV1/FVC低値

- 肺感染症の合併

- 慢性誤嚥

- 急性および慢性GVHD

- レシピエントの比較的高齢

- 不一致ドナーの採用

- 高用量の前処置(強度減弱前処置と比較して)

閉塞性細気管支炎の臨床経過はさまざまであるが、患者は強化免疫抑制療法を開始しているにもかかわらず、進行性および消耗性の呼吸不全を発症する頻度が高い。

閉塞性肺疾患に対する標準治療では、強化免疫抑制療法と、抗微生物予防、気管支拡張薬による治療、酸素補給(適応がある場合)などの支持療法が併用される。[ 146 ]閉塞性肺疾患の発生機序における腫瘍壊死因子αの潜在的役割から、エタネルセプトなどの中和剤が有望であることが示唆されている。[ 147 ]

拘束性肺疾患

拘束性肺疾患は、FVC、全肺気量(TLC)、およびDLCOの低下により定義される。閉塞性肺疾患とは対照的に、FEV1/FVC比は100%近く維持される。拘束性肺疾患はHSCT後に一般的で、100日目までに患者の25%~45%に報告されている。[ 137 ]重要なことに、HSCT後、100日経過時および1年経過時にみられるTLCまたはFVCの低下は、再発以外による死亡率の増加に関連している。初期の報告により、拘束性肺疾患の発生率はレシピエントの年齢が進むとともに増加することが示唆されたが、その後の研究でHSCTを受けた小児において重篤な拘束性肺疾患が明らかにされている。[ 148 ]

最も認識しやすい拘束性肺疾患の型は、器質化肺炎を伴う閉塞性細気管支炎(BOOP)であり、最近では特発性器質化肺炎(COP)と呼ばれている。臨床的特徴としては、乾性咳嗽、息切れ、発熱などがある。X線所見としては、気腔の浸潤影(airspace consolidation)と一致するびまん性、周辺性、綿毛状の浸潤がみられる。報告頻度はHSCTレシピエントの10%未満であるが、BOOP/COPの発生には過去の急性および慢性GVHDが強く関連する。[ 143 ]

拘束性肺疾患患者では、コルチコステロイド、シクロスポリン、タクロリムス、アザチオプリンなどの複数の薬剤に対する反応が限られている。[ 146 ]拘束性肺疾患の発生機序における腫瘍壊死因子αの潜在的役割から、エタネルセプトなどの中和剤が有望であることが示唆されている。[ 147 ]

詳しい情報については、「小児がんに対する治療の晩期障害」のHSCTに伴う呼吸器合併症のセクションを参照のこと。

泌尿器系の晩期障害

腎疾患

移植後には慢性腎臓病がしばしば診断される。慢性腎臓病には多くの臨床型があるが、最も一般的に記載される臨床型として、血栓性微小血管症、ネフローゼ症候群、カルシニューリン阻害薬毒性、急性腎障害、GVHD関連慢性腎臓病などがある。慢性腎臓病の発生と関連するさまざまな危険因子が報告されている。しかしながら、最近の研究では急性および慢性GVHDが腎障害の直接的な原因であることが示唆されている。[ 34 ]

HSCTを受けた28コホートの成人および小児計9,317人を対象としたシステマティックレビューでは、約16.6%(範囲、3.6%~89%)の患者が移植後最初の1年以内に慢性腎臓病(推算糸球体濾過量の少なくとも24.5 mL/min/1.73m2の低下と定義)を発症した。[ 149 ]移植後約5年経過時に発症する慢性腎疾患の累積発生率は、移植の種類と慢性腎臓病の病期によって4.4%~44.3%に及んでいた。[ 150 ][ 151 ]この状況での慢性腎臓病患者の死亡率は、正常な腎機能を維持していた移植レシピエントの死亡率よりも高く、これは併存疾患について調整された場合でも変わらなかった。[ 152 ]

HSCT後の患者で、特にカルシニューリン阻害薬で長期間治療されている患者では、高血圧を積極的に治療することが重要である。HSCT後にアルブミン尿および高血圧が認められる患者がアンジオテンシン変換酵素(ACE)阻害薬またはアンジオテンシン受容体遮断薬による治療で有益性が得られるかどうかについてはさらなる研究が必要であるが、ある小規模研究では、ACE阻害薬のカプトプリルによる高血圧の慎重なコントロールで有益性が示された。[ 153 ]

QOL

健康関連QOL(HRQL)

HRQLは、健康問題の全般的なQOLへの影響に関連して、ある個人の機能状態および健康感の主観的評価を組み込んだ多次元構造を有している。[ 154 ][ 155 ]多くの研究で、HRQLは以下の因子によって異なることが示されている:[ 156 ]

- HSCT後の期間:HRQLはHSCTを最近受けた場合はより不良である。

- 移植の種類:非血縁ドナーを用いたHSCTのレシピエントは、自家または同種血縁ドナーを用いたHSCTのレシピエントよりもHRQLが不良である。

- HSCT関連続発症の有無:HRQLは慢性GVHDが認められる場合はより不良である。

家族の団結や小児の適応能力など、HSCT前の因子がHRQLに影響することが示されている。[ 157 ]いくつかのグループでもまた、小児のHSCT後のHRQLに対する親の評価についてHSCT前の育児ストレスの重要性が確認されている。[ 157 ][ 158 ][ 159 ][ 160 ][ 161 ]HSCT後12カ月にわたるHRQLの経過報告で、HRQLはHSCT後3カ月で最も不良となり、その後着実に改善することが示された。非血縁ドナー移植のレシピエントは、ベースライン時から3カ月経過時までHRQLが最も急激に低下した。別の研究の報告によると、急性回復期における情緒的機能の障害、高レベルの不安、およびコミュニケーションの不足は、HSCT後1年経過時のHRQLにマイナスの影響を及ぼした。[ 162 ]複数の縦断研究により、以下に示す追加のベースライン危険因子とHSCT後のHRQL経過との関連が特定された:

HSCTの個々の合併症による影響を調査した報告では、重度の末端器官毒性、全身感染症、またはGVHDを有する小児でHRQLがより不良であることが示された。[ 158 ]複数の横断研究により、5年以上生存している小児HSCT生存者について心理学的、認知的、または身体的問題がHRQLに負の影響を与えるようであるが、HRQLは適度に良好であることが報告された。女性、HSCTの適応となった診断(例:急性骨髄性白血病の患者はHRQLがより不良であった)とHSCT前の治療の強度は、いずれもHSCT後のHRQLに影響を及ぼす因子と同定された。[ 168 ][ 169 ]最後に、HSCT後5~10年が経過した小児を対象にする別の横断研究では、小児の脆弱性に関する親の懸念が過保護な育児を誘発しうることが警告された。[ 161 ]

機能的転帰

医師により報告された身体機能

以下の研究で報告されているように、小児のHSCT生存者における長期的な身体機能障害に関する臨床医の報告では、機能喪失の頻度および重症度は低いことが示唆されている:

- European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantationの研究では、647人のHSCT生存者(5年以上生存)における転帰の報告にKarnofskyのパフォーマンススケールが用いられた。[ 170 ]このコホートでは、生存者の40%が移植を受けた時点で18歳未満であった;Karnofskyスコアが100未満であったのはわずか19%であった。7%が労働することが不可能と定義されるスコア80未満であった。他の2つのグループで臨床医が分類する不良な機能的転帰についても同様に低い割合が報告された。[ 168 ][ 171 ]

- City of Hope National Medical CenterおよびStanford University Hospitalで治療を受けた小児同種HSCTの生存者50人では、全員のKarnofskyスコアが90または100であった。[ 171 ]

- Karolinska University Hospitalで治療を受けた73人の若年成人(平均年齢、26歳)におけるHSCT後10年経過時のKarnofskyスコアの中央値は90であった。[ 168 ]

自己報告による身体機能

小児HSCT生存者における自己報告または代理人のデータでも同様に機能喪失の割合が低いことが以下の研究で示された:

このほかに機能制限を報告している研究として以下のものがある:

- 小児期にHSCTを受けた生存者235人を対象としたBone Marrow Transplant Survivors Study(BMTSS)では、17%が長期の身体機能の制限を報告したのに対し、同胞比較群では8.7%であった。[ 174 ]

- シアトルの1つの研究では、年齢中央値11.9歳で移植を受けた214人の若年成人(質問票による調査時の年齢中央値、28.7歳;男性、118人)において身体機能が評価された。年齢および性別で調整した対照と比較した場合、このコホートのHSCT生存者では、SF-36の身体コンポーネントスコア、身体機能および日常役割機能のサブスケール、生活の質尺度で標準偏差が半分の低い値を示した。[ 169 ]

- スウェーデンの研究でも、移植後中央値で10年経過した若年成人(年齢中央値、26歳)のHSCT生存者73人において、自己報告による低い身体的健康が確認された。HSCT生存者のスコアは、身体機能(HSCT生存者で90.2 vs 集団で95.3)、身体的健康への満足(HSCT生存者で66.0 vs 集団で78.7)、および身体的健康による役割の制限(HSCT生存者で72.7 vs 集団で84.9)について、集団の基準値を有意に下回っていた。[ 168 ]

測定による身体機能

小児HSCT患者および生存者集団における機能の客観的な測定は、身体能力の喪失が臨床医や自己報告によるデータに依存した研究で明らかにされるよりも大きな問題になりうることを暗に示している。心肺機能適応を測定した研究により、以下が観察されている:

- 1つの研究では、HSCT前の小児および若年成人20人、HSCT後1年の患者31人、および健康な対照70人の集団において自転車エルゴメーターによる運動能力が採用された。[ 175 ]最大酸素摂取量の平均値は、HSCT前の集団で21 mL/kg/min、HSCT後の集団で24 mL/kg/min、および健康な対照で34 mL/kg/minであった。HSCT生存者のうち、がん診断を受けた患者の62%が健康な対照における最大酸素摂取量の最下位5パーセンタイル値に相当した。

- 別の研究では、小児HSCT生存者31人において、Bruceトレッドミルプロトコルを用いて運動能力が調査された。このコホートでは、HSCT生存者の25.8%が予測されたカテゴリーの70%~79%という運動能力を有し、41.9%が予測されたカテゴリーの70%未満という運動能力を有した。[ 176 ]

- 3つ目の研究では、平均11.3歳で移植を受けたHSCT生存者33人の運動能力が調査された。HSCT後5年経過時点では、連続的な自転車エルゴメーター検査で75パーセンタイル値を超えるスコアが得られたのは生存者33人中わずか4人であった。[ 177 ]

フォローアップのためのガイドライン

HSCT後の晩期障害に対するフォローアップに関するコンセンサスガイドラインが、いくつかの組織から公表されている。CIBMTRは、American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplant(ASBMT)と共同で、また他の5つの国際移植グループとも協力して、HSCTの長期生存者に対するスクリーニングおよび予防に関するコンセンサスに基づく推奨を発表した。[ 179 ]

このガイドラインでは、小児に特異的な課題の一部が扱われているが、扱われていない重要な小児科的問題も数多くある。それらの問題の一部は、Children's Oncology Group (COG)とその他の小児がん研究グループ(英国、スコットランド)が発表した一般的なガイドラインで部分的に扱われている。COGもHSCT後の晩期障害サーベイランスに関するより具体的な推奨を公表している。[ 180 ]小児患者に特異的な晩期障害に関する詳細データやHSCT後の長期フォローアップに関するガイドラインが不足していることに対応するべく、Pediatric Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Consortium(PTCTC)は、既存のデータについて概説し、小児患者に特異的な問題に対する専門家の推奨とともに主要なグループ(CIBMTR/ASBMT、COG、および英国)による推奨を要約した6編の詳細な論文を発表した。[ 9 ][ 34 ][ 64 ][ 181 ][ 182 ][ 183 ]

小児患者に特異的なフォローアップガイドラインをさらに標準化および調和させるための国際努力が進行中であるが、PTCTCの要約およびガイドラインの推奨では、HSCT後の小児に対する晩期障害のモニタリングに関するコンセンサスの概要が提示されている。[ 64 ]

参考文献- Sun CL, Francisco L, Kawashima T, et al.: Prevalence and predictors of chronic health conditions after hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood 116 (17): 3129-39; quiz 3377, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bhatia S, Francisco L, Carter A, et al.: Late mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation and functional status of long-term survivors: report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood 110 (10): 3784-92, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Holmqvist AS, Chen Y, Hageman L, et al.: Severe, life-threatening, and fatal chronic health conditions after allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation in childhood. Cancer 129 (4): 624-633, 2023.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bhatia S, Robison LL, Francisco L, et al.: Late mortality in survivors of autologous hematopoietic-cell transplantation: report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood 105 (11): 4215-22, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, et al.: Reduced mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 363 (22): 2091-101, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Martin PJ, Counts GW, Appelbaum FR, et al.: Life expectancy in patients surviving more than 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 28 (6): 1011-6, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LC, et al.: Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA 297 (24): 2705-15, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al.: Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 355 (15): 1572-82, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bhatia S, Davies SM, Scott Baker K, et al.: NCI, NHLBI first international consensus conference on late effects after pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation: etiology and pathogenesis of late effects after HCT performed in childhood--methodologic challenges. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 17 (10): 1428-35, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Behar E, Chao NJ, Hiraki DD, et al.: Polymorphism of adhesion molecule CD31 and its role in acute graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med 334 (5): 286-91, 1996.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Goodman RS, Ewing J, Evans PC, et al.: Donor CD31 genotype and its association with acute graft-versus-host disease in HLA identical sibling stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 36 (2): 151-6, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- van Dalen EC, van der Pal HJ, Kok WE, et al.: Clinical heart failure in a cohort of children treated with anthracyclines: a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Cancer 42 (18): 3191-8, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Duncan CN, Brazauskas R, Huang J, et al.: Late cardiovascular morbidity and mortality following pediatric allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 53 (10): 1278-1287, 2018.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Chow EJ, Mueller BA, Baker KS, et al.: Cardiovascular hospitalizations and mortality among recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Intern Med 155 (1): 21-32, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Armenian SH, Sun CL, Francisco L, et al.: Late congestive heart failure after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 26 (34): 5537-43, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Armenian SH, Sun CL, Mills G, et al.: Predictors of late cardiovascular complications in survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16 (8): 1138-44, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Armenian SH, Sun CL, Kawashima T, et al.: Long-term health-related outcomes in survivors of childhood cancer treated with HSCT versus conventional therapy: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study (BMTSS) and Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). Blood 118 (5): 1413-20, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Arvidson J, Kihlgren M, Hall C, et al.: Neuropsychological functioning after treatment for hematological malignancies in childhood, including autologous bone marrow transplantation. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 16 (1): 9-21, 1999 Jan-Feb.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Barrera M, Atenafu E: Cognitive, educational, psychosocial adjustment and quality of life of children who survive hematopoietic SCT and their siblings. Bone Marrow Transplant 42 (1): 15-21, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kupst MJ, Penati B, Debban B, et al.: Cognitive and psychosocial functioning of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients: a prospective longitudinal study. Bone Marrow Transplant 30 (9): 609-17, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Phipps S, Brenner M, Heslop H, et al.: Psychological effects of bone marrow transplantation on children and adolescents: preliminary report of a longitudinal study. Bone Marrow Transplant 15 (6): 829-35, 1995.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Phipps S, Rai SN, Leung WH, et al.: Cognitive and academic consequences of stem-cell transplantation in children. J Clin Oncol 26 (12): 2027-33, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Phipps S, Dunavant M, Srivastava DK, et al.: Cognitive and academic functioning in survivors of pediatric bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol 18 (5): 1004-11, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cognitive functioning after BMT. In: Pot-Mees CC: The Psychological Effects of Bone Marrow Transplantation in Children. Eburon Delft, 1989, pp 96–103.[PUBMED Abstract]