ご利用について

医療専門家向けの本PDQがん情報要約では、がん患者の介護者に対する課題および有用な介入について包括的な、専門家の査読を経た、そして証拠に基づいた情報を提供する。本要約は、がん患者を治療する臨床家に情報を与え支援するための情報資源として作成されている。これは医療における意思決定のための公式なガイドラインまたは推奨事項を提供しているわけではない。

本要約は編集作業において米国国立がん研究所(NCI)とは独立したPDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Boardにより定期的に見直され、随時更新される。本要約は独自の文献レビューを反映しており、NCIまたは米国国立衛生研究所(NIH)の方針声明を示すものではない。

CONTENTS

- 概要

-

家族等による介護は、無報酬の個人による個人的な介護の提供、医療の支援、家事を行うこと、外部サービスの手配、定期的な訪問、または対処における支援の提供として広く定義される。[ 1 ][ 2 ]家族等介護者(英語ではinformal caregiverとも呼ばれる)は通常、親族または友人であり、介護を要するがんの個人と同じ所帯で暮らしている場合もあれば、暮らしていない場合もある。

家族等による介護では、重要な実際的および経済的な便益が提供される。本要約では、がん患者の家族等介護者における経験について記述し、介護者の負担(しばしばマイナスの心理的結果に関連する)の危険因子を列挙し、家族等による介護の負担を減らすようにデザインされた証拠に基づく介入を評価する。本要約の目的は、腫瘍科の臨床医に家族等介護者の重要性のより深い理解と、負担を背負う介護者を認識し、有効に介入するために必要な情報の両方を提供することである。

家族等介護者が誰で、彼らが果たす役割は何か?

2016年に、National Alliance for Caregiving(NAC)により、がん患者に介護を提供したと自己特定した介護者111人における回答の分析結果が報告された。[ 3 ]回答者は、調査前の12ヵ月間にわたって成人の親族または友人に対して無報酬の介護を提供した成人の介護者の代表サンプルを確認したはるかに大規模な研究の一部であった。

以下の所見から、がん患者に対する家族等介護者の寸描および彼らが直面する課題が提供されている:

介護はまた関係性も示す。[ 4 ][ 5 ]また、患者と介護者との相関性には腫瘍科の臨床医が認識しておくべき重要な意味合いがあり、それには以下のものがある:

介護の心理的結果

介護の心理的結果には大きな幅がある。心的外傷後の成長/便益の発見といったプラスの結果を報告する介護者もいる。一方で、不安、抑うつ、または心的外傷後ストレス障害(PTSD)を経験する介護者も少数存在する。以下の段落で、注目すべき文献を要約する。

便益の発見:成人がん生存者[ 11 ][ 12 ]または小児がん生存者[ 13 ][ 14 ]のいずれかの介護者を対象にした数件の定性研究(面談または物語形式の質問票)の結果から、介護のプラスの側面について以下のような共通したテーマが明らかにされた:

- パートナーや子供を含めた他者とのより親密な関係。

- 生命のより大きな感謝。

- 人生の優先順位の明確化。

- 信仰心の高まり。

- 他者へのより高い共感。

- より良い健康習慣。

Benefit Finding Scaleを用いることで、こうした共通したテーマはより定量的に測定される。介護者の個人的成長について、以下の6つの領域が明らかにされており[ 15 ]、生存者の介護者と死別を経験した介護者の両者で一貫している:[ 16 ]

- 受容。

- 共感。

- 感謝。

- 家族。

- 自己のプラスのイメージ。

- 優先順位の再定義。

不安および/または抑うつ:数件の大規模調査研究により、不安および抑うつの有病率および潜在的な共変量のより正確な推定値または危険因子が提供されている;これらを以下に要約する。

- 腎細胞がん患者の介護者196人について、心理的適応と介護者の経験および満たされていない要求との関連を研究するために電話による調査が実施された。研究者らにより、介護者の64%で重要な要求が1つ以上満たされていないこと;53%で3つ以上要求が満たされていないこと;および29%で10個以上要求が満たされていないことが実証された。[ 17 ]不安の増加が回答者の29%で示され、抑うつが回答者の11%で示された。満たされない情報ニーズおよび手術中のケアの不良な経験が、介護者の抑うつに対する危険因子であった。満たされない情報ニーズは不安に対する唯一の危険因子であった。

- 進行期の肺がんまたは大腸がん患者の介護者もまた、比較的高いレベルの不安または抑うつを報告した。早期緩和ケアに関するランダム化試験に登録された患者の介護者に関するベースラインデータの横断的解析[ 18 ]において、かなりの割合の介護者が高いレベルの不安(42.2%)または抑うつ(21.5%)を報告した。介護者の抑うつに対する危険因子は、患者が治癒を期待していることおよび情動的サポート対処を患者が利用することであった。患者の受容コーピングの利用は、介護者の不安とはあまり関連していなかった。膵がん患者の介護者を対象にした1件の研究でも同様の結果が報告された:地域の標準と比較して、介護者の39%が高いレベルの不安を示し、14%が高いレベルの抑うつを示した。[ 19 ]

PTSD:長期に及ぶ介護のマイナスの結果の1つはPTSDである。診断から6ヵ月経過時の頭頸部がん患者の介護者を対象にした1件の予備研究で、約20%がPTSDの基準を満たしたことが実証された。[ 20 ]PTSDに対する危険因子には、以下のものがあった:

- 介護者が治療の有益性の低さを認識していること。

- 介護者が患者の症状が多いと認識していること。

- 介護者が回避的対処戦略を採っていること。

また同じ研究者らにより、同様の集団において疾患の認識における差は6ヵ月にわたって動的であったが、患者における健康関連の生活の質(QOL)が低下すると差が大きくなることが実証された。[ 21 ]

介護者のQOLの低下:いくつかの研究者集団により、介護者のQOLの測定値が発表されている。1件の研究で、造血幹細胞移植を受けた患者の介護者はMedical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey(SF-36)の身体的および精神的側面で測定されるQOLの低下を経験することが実証された。[ 5 ]

要約すると、介護者はがん患者に対して不可欠なサポートと資源を提供する。しかしながら、家族等介護者の役割は、介護者の資源を超え、最終的にはマイナスの心理的結果を引き起こしうる要求を生み出す。本要約ではこれより、要求が満たされず、身体的および心理的苦痛の増加を経験している少数ではあるが重要な介護者に焦点を当てる。介護者の負担の概念について簡単なレビューを行った後、介護者に対する要求、介護者が尊重している資源、潜在的な調節器、および対処戦略に関する情報を示す。

参考文献- Caregiving in the U.S. 2015. Bethesda, Md: National Alliance for Caregiving, 2015. Available online. Last accessed October 15, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kim Y, Kashy DA, Kaw CK, et al.: Sampling in population-based cancer caregivers research. Qual Life Res 18 (8): 981-9, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cancer Caregiving in the U.S.: An Intense, Episodic, and Challenging Care Experience. Bethesda, Md: National Alliance for Caregiving, 2016. Available online. Last accessed October 15, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Litzelman K, Green PA, Yabroff KR: Cancer and quality of life in spousal dyads: spillover in couples with and without cancer-related health problems. Support Care Cancer 24 (2): 763-771, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- El-Jawahri AR, Traeger LN, Kuzmuk K, et al.: Quality of life and mood of patients and family caregivers during hospitalization for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer 121 (6): 951-9, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kershaw T, Ellis KR, Yoon H, et al.: The Interdependence of Advanced Cancer Patients' and Their Family Caregivers' Mental Health, Physical Health, and Self-Efficacy over Time. Ann Behav Med 49 (6): 901-11, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Litzelman K, Kent EE, Mollica M, et al.: How Does Caregiver Well-Being Relate to Perceived Quality of Care in Patients With Cancer? Exploring Associations and Pathways. J Clin Oncol 34 (29): 3554-3561, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Mosher CE, Adams RN, Helft PR, et al.: Family caregiving challenges in advanced colorectal cancer: patient and caregiver perspectives. Support Care Cancer 24 (5): 2017-2024, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Libert Y, Merckaert I, Slachmuylder JL, et al.: The ability of informal primary caregivers to accurately report cancer patients' difficulties. Psychooncology 22 (12): 2840-7, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Mazer BL, Cameron RA, DeLuca JM, et al.: "Speaking-for" and "speaking-as": pseudo-surrogacy in physician-patient-companion medical encounters about advanced cancer. Patient Educ Couns 96 (1): 36-42, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Mosher CE, Adams RN, Helft PR, et al.: Positive changes among patients with advanced colorectal cancer and their family caregivers: a qualitative analysis. Psychol Health 32 (1): 94-109, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Von Ah D, Spath M, Nielsen A, et al.: The Caregiver's Role Across the Bone Marrow Transplantation Trajectory. Cancer Nurs 39 (1): E12-9, 2016 Jan-Feb.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Willard VW, Hostetter SA, Hutchinson KC, et al.: Benefit Finding in Maternal Caregivers of Pediatric Cancer Survivors: A Mixed Methods Approach. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 33 (5): 353-60, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hensler MA, Katz ER, Wiener L, et al.: Benefit finding in fathers of childhood cancer survivors: a retrospective pilot study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 30 (3): 161-8, 2013 May-Jun.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kim Y, Schulz R, Carver CS: Benefit-finding in the cancer caregiving experience. Psychosom Med 69 (3): 283-91, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kim Y, Carver CS, Schulz R, et al.: Finding benefit in bereavement among family cancer caregivers. J Palliat Med 16 (9): 1040-7, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Oberoi DV, White V, Jefford M, et al.: Caregivers' information needs and their 'experiences of care' during treatment are associated with elevated anxiety and depression: a cross-sectional study of the caregivers of renal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 24 (10): 4177-86, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Fishbein JN, et al.: Factors associated with depression and anxiety symptoms in family caregivers of patients with incurable cancer. Ann Oncol 27 (8): 1607-12, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Janda M, Neale RE, Klein K, et al.: Anxiety, depression and quality of life in people with pancreatic cancer and their carers. Pancreatology 17 (2): 321-327, 2017 Mar - Apr.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Richardson AE, Morton RP, Broadbent EA: Illness perceptions and coping predict post-traumatic stress in caregivers of patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer 24 (10): 4443-50, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Richardson AE, Morton RP, Broadbent EA: Changes over time in head and neck cancer patients' and caregivers' illness perceptions and relationships with quality of life. Psychol Health 31 (10): 1203-19, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 介護者の負担

-

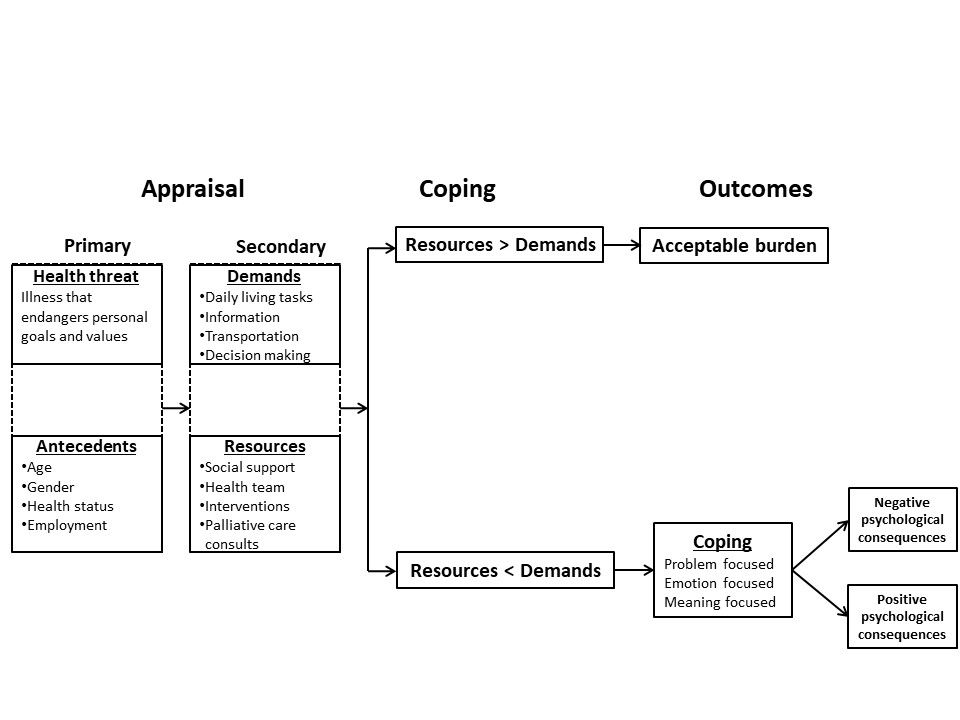

介護者の負担という用語は、介護の要求に対する介護者の自己分析の結果およびそうした要求に取り組むために利用可能な認識している資源を示す。Transactional Model of Stress and Coping(ストレスと対処の相互規定的作用モデル)(下の図を参照のこと)は、介護者の要求、資源、負担、および負担の心理的結果の関係を示す有用な枠組みである。[ 1 ]この観点から考えると、負担は介護者に対する要求が、介護者が利用可能な資源を超える場合に認識される。

その過程は、健康への脅威および介護者への何らかの要求の関連性に関する判断である一次評価から始まる。関連していると判断された要求は、利用可能な資源でその要求を低減または克服できるかどうかの可能性を評価するため、二次評価を受ける。要求の困難さが利用可能な資源を上回っている場合に、負担が重いと認識される。対処戦略もまた、認識された負担の心理的結果がマイナスであるかプラスであるかを明らかにする場合がある。

Transactional Model of Stress and Copingにより、一部の介護者が負担およびマイナスの心理的結果を経験する理由が説明される。臨床医は、要求を低減し、資源を増やし、あるいは選択的な対処を促進する介入を行える。前歴、要求、および資源についての記述は、本要約の本文の例からである。 前掲のTransactional Model of Stress and Copingは妥当性が確認されたわけではなく、本要約の残りの部分を構成する働きをしている。

一次評価:家族等介護者への要求

面談の定性分析:化学療法を受けた患者の家族等介護者48人を対象として複数の方法を組み合わせた研究により、いくつかの注目すべき所見が示された。[ 2 ]第一に、介護者の68%では満たされていない要求が0~1つであった;その一方で、少数の介護者(23%)では、満たされていない要求が5~10個であった。第二に、最も一般的な要求は、化学療法のリスクと潜在的な有益性に関する情報(79%)および在宅での副作用の管理に関する情報(78%)であった。この他の情報関連の要求としては、セルフケア、補完代替医療、地域コミュニティの資源に関する情報が含まれた。

1つの研究者グループにより、治療完了後6ヵ月以内の頭頸部がん患者6人およびその配偶者が面談された。テーマ分析により、副作用に対するより良い準備、回復のより明確な予定表、治療中に患者と配偶者が経験する感情に対処する戦略など、いくつかの満たされていない要求が示された。[ 3 ]

悪液質の症状または徴候がみられるがん患者の家族等介護者を対象にした定性研究の系統的レビューにおいて、介護者の生活の複雑さがさらに強調されている。[ 4 ]以下のテーマが確認された:

- 毎日の生活への影響。

- 介護を引き受ける介護者の努力。

- 医療提供者投入の必要性。

- 患者との対立。

- 負の感情。

調査:介護者の要求をより正確に評価するため、1つの研究者グループにより、Supportive Care Needs Survey-Partners and Caregivers(SCNS-P&C)が開発され、精神測定学的妥当性が実証された。[ 5 ]1件のがん生存者研究に登録された患者の介護者500人以上が解析のための調査に回答した。介護者の平均年齢は60.6歳(範囲、16~85歳)であった。

生存者の診断は以下の通りであった:

- 前立腺がん(32%)。

- 血液がん(16.3%)。

- 乳がん(13.2%)。

- 黒色腫(11.5%)。

- 大腸がん(11.3%)。

- 頭頸部がん(8.6%)。

- 肺がん(7.1%)。

解析から、以下の4つの分野の要求が明らかにされた:

- 医療サービス分野。

- 心理的および感情的分野。

- 仕事および社会的分野。

- 情報分野。

腎細胞がん患者の介護者196人を対象に電話による調査をSCNS-P&Cを用いて実施した研究者らにより、介護者の64%で重要な要求が1つ以上満たされていないこと;53%で3つ以上要求が満たされていないこと;および29%で10個以上要求が満たされていないことが実証された。[ 6 ]要求の各分野について、要求が中等度または高度に満たされていないと報告した回答者の割合は以下の通りであった:

- 医療サービス分野、30%。

- 心理的および感情的分野、30%。

- 仕事および社会的分野、23%。

- 情報分野、18%。

別の研究において、188組の患者-介護者により、SCNS-P&Cが記入された。[ 7 ]介護者は女性が大多数を占めた;平均年齢は57.8歳であった。介護者は患者よりも高いレベルの苦痛および不安を報告した。満たされていない要求はないと報告した介護者は少数(14%)で、多くの介護者(44%)が満たされていない要求が10個以上あると報告した。介護者の主要な満たされていない要求は、以下の通りであった:

- 患者の状態に関する恐怖を管理するサポート。

- 疾患に関する情報を受けること。

- 介護者自身のための感情面のサポートを受けること。

介護者の要求の強力な予測因子は認められなかった;しかしながら、患者の満たされていない要求と介護者の不安は、介護者における満たされていない要求とわずかに関連していた。

同様に、台湾における166組の肺がん患者-介護者に対してSCNS-P&Cが実施された。[ 8 ]最上位の満たされていない要求は、情報ニーズであった。

介護者の作業:1件の横断研究により、日常生活活動(ADL)において患者を支援すると介護者の負担が増加することが実証された。[ 9 ]この研究には、がんの高齢の成人(年齢が65歳を超える)の介護者100人が登録された。介護者はほとんどが女性で、患者と結婚し、一緒に暮らしていた。雇用状態およびADLにおける支援は多変量解析で負担の増加に対する危険因子であった。同様に、590人の介護者を対象にした調査で、主要な介護者はかなりの作業負荷を引き受けていたことが示された。[ 10 ]結果として、介護者は、雇用および社会的関係の維持が困難となり、財政的な困難を抱えていた。一方で、主要な介護者はその経験を通じて最も大きな個人的成長を経験していた。2件の研究の結果は、その後の系統的レビューによって支持されている。[ 11 ]さらに微妙な違いを示す見解として、認識された負担と心理的結果は何らかの与えられた介護者の作業に対して精通している感覚に関係している可能性がある。[ 12 ]

二次評価:家族等介護者のための資源

以下の一覧は、介護者が複数の研究で重要であると確認した資源を記録したものである:

- 家族等介護者の役割、責任、および課題を医療提供者が認識していること。

- 治療計画、目標、予想される合併症または副作用、および可能性の高い転帰に関する情報。

- 疾患の経過全体にわたって患者の身体および感情面での健康の変化に対応する方法に関する指導。

- (介護者が最も頻繁に準備ができていないおよび訓練を受けていない)役割のストレスに対処する際のサポート。

- 注射の実施、創傷のケア、副作用の管理など、介護者が行うことを期待される医療および看護作業に関する詳細な教育。

介護者の負担の潜在的な調節器

介護者の負担増加に関連する因子には以下がある:

- 女性。

- 年齢(比較的年齢が低い介護者および健康状態を害している高齢の介護者)。

- 人種および民族性。

- 比較的低い社会経済的状態。

- 雇用状態。

- 役割緊張。

- ケアの場所。

女性

女性は負担増加に対する確立された危険因子である。[ 13 ]進行がん患者の自己特定した介護者308人を対象にした1件の調査では、女性介護者の負担増加の潜在的な決定要因を特徴付けるよう模索された。[ 14 ]結果から、希望およびサポートの要求の実現の認識が、男女双方で負担に対する最も重要な予防因子であることが実証された。雇用されているか、または情動焦点型対処を用いた女性は、負担を認識する可能性が高かった。結果から、役割緊張に取り組み、代替の対処戦略を発達させる介入が有用であると示唆されている。

年齢

家族介護者は、しばしば覚悟ができていないと感じていて、知識が不十分で、がん患者を介護するための腫瘍チームの指導をほとんど受けていない。[ 15 ]高齢の介護者は併存疾患を有し、固定収入に頼って暮らしており、利用可能な社会支援ネットワークが縮小している場合があるため、特に弱い立場にある。また、がん患者の高齢の介護者は自身の健康の要求を顧みず、運動する時間が少なく、自身の処方薬物の摂取を忘れ、睡眠が途切れがちで疲労しがちである。そのため、高齢者による介護が不良な身体的健康や抑うつにつながることは一般的であり、死亡の増加につながることもある。[ 16 ][ 17 ]

年齢が低い介護者ほど、一般的に仕事、自身の家庭での責任、および社会生活に関する犠牲が大きい。中年の介護者は典型的に失われた労働時間、仕事の中断、休暇の取得、および生産性の低下について心配する。[ 18 ][ 19 ]

人種および民族性

116件の経験的研究のメタアナリシスにおいて、アジア系米国人介護者は、白人、アフリカ系米国人、およびヒスパニック系の介護者よりも長時間介護を提供し;公的支援サービスの利用水準が低く;他のサブグループよりも財源が少なく、教育水準が低く、抑うつのレベルが高いことが明らかにされた。[ 20 ]これらの知見は、外部からの助けを受けていない介護者は助けを受けている介護者よりも抑うつ状態にあるため、腫瘍チームにとって重要である。

アジア系米国人介護者における満たされていない要求と、サービスの障壁について調べた1件の研究では、介護者は「自尊心が高過ぎて外部からの助けを受けられないと感じている」または「部外者に入って来てもらいたくない」ために外部からの助けを断ったことが明らかにされた;報告された他の障壁としては、「お役所仕事はあまりに複雑である」または「資格を有する介護提供者を見つけられない」が挙げられた。[ 21 ]アジア系米国人によるホスピスの利用に関する1件の研究で、アジア系米国人の間では死または死ぬという話題は縁起が悪いと考えられており、そのため予後およびインフォームドコンセントの話し合いは非常に困難となるため、彼らが疾患について家族での話し合いに乗り気でない結果、ホスピス利用率が低くなっていることが明らかにされた。[ 22 ]がんの診断を患者に秘密にしておくことや疾患進行の話し合いを回避することは、介護者の負担および責任の感覚を大きくすることがある。

同様に、ヒスパニック系およびアフリカ系米国人患者および介護者は、カウンセリングやサポートグループ、在宅ケア、居住型療養施設、ホスピスサービスなど地域の健康資源をあまり利用していない。1つの重要な理由は、家族の強い結びつきによって、マイノリティの介護者は家族外からの助けを求めることを避けているということである。[ 23 ]アフリカ系米国人、白人、およびヒスパニック系の介護者を比較した1件の研究により、ヒスパニック系患者の75%およびアフリカ系米国人患者の60%が主要な介護者の家族と同居していることが明らかにされた。マイノリティの家族は、友人および親族からの非公式な介護に頼っていることが多く、白人の家族よりも大きな社会支援ネットワークをもっていた。しかしながら、高齢の家族のメンバーに介護を提供するというこうした義務感の高さは、白人の介護者によって報告されているよりも長い介護時間、介護についての大きな諦め、高いレベルの介護者の緊張、および家計収入の大きな低下と関連した。[ 23 ][ 24 ]

別の研究では、介護による雇用喪失の報告が分析された。結果から、アフリカ系米国人およびヒスパニック系の介護者の方が、白人の介護者よりも患者の介護のために労働時間を減らす傾向が高かったことが示された。さらに、マイノリティの介護者は愛する人のために公的なナーシングホームサービスを利用したがらなかった。ナーシングホームに親族を入所させるよりもむしろ労働時間を減らす決定は、心理的、社会的、および経済的負担の増加を伴った。[ 25 ]

社会経済的状態

介護に必要な実質的な自己負担費用は、がん患者の家族に経済的負担を生じさせることがある。個人収入および家計収入が低いおよび経済的制約のある家族ではまた、治療の非遵守または収入に基づいてなされる治療関連の決定が危機にさらされる場合もある。[ 26 ]

雇用

家族等による介護は、家族に対して経済的な負担を課すことが知られている。1件の研究により、U.S. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey(MEPS) Experiences with Cancer Survivorship Survey(ECSS)に回答したがん生存者458人およびLIVESTRONG 2012 Survey for People Affected by Cancer(SPAC)に回答したがん生存者4,706人からのデータが解析された。結果から、MEPS ECSSに回答した生存者の25%およびSPACに回答した生存者の29%が、彼らの介護者は有給または無給休暇の取得、および/または労働時間、職務、または雇用状態の変更など、雇用を大きく変更したと報告したことが示された。[ 27 ]進行がん患者の介護者70人の労働生産性は、失われた労働のために23%低下したことが示された。[ 28 ]介護が長時間に及ぶほど生産性の喪失が大きくなり、生産性の喪失は介護者の抑うつおよび不安の割合の高さに関連した。進行がん患者の介護者89人を対象にした1件の研究により、69%が何らかの形で仕事に悪影響があることを報告した;この割合は終末期には77%に増加したことが示された。[ 29 ]

一部の研究により、疾患および人口統計学的特徴から評価した、介護の経済的負担における漸増的増加が示されている。進行乳がん女性の介護者78人を対象にした研究により、生産性の喪失(常習欠勤および仕事での生産性の低下)は、無病状態の女性の介護者よりも進行疾患の女性の介護者で大きかったことが示された。[ 30 ]肺がんおよび大腸がん患者の介護者1,629人を対象にした1件の調査で、経済的負担は肺がん患者および4期疾患患者の介護者で最も重いことが示された。[ 31 ]介護者54人(アフリカ系米国人またはヒスパニック系が35%)を対象にした1件の研究により、マイノリティの介護者は白人の介護者よりも雇用および財政に関する大きな苦痛を報告したことが示された。[ 32 ]前立腺がん男性のパートナーの介護者を対象にした1件の研究により、収入の低い($40,000未満/年)介護者は収入の高い介護者よりも家族等による介護に多くの時間を費やすことが示された。[ 33 ]

Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993(1993年の育児介護休業法:FMLA)は、従業員が自身の重篤な医学的状態または親族の重篤な医学的状態のために、利益または仕事を失うことなく休暇を取る選択肢を従業員に与えるためにデザインされた。[ 34 ]家族のメンバーは法の下で最長12週間の休暇を取る権利が与えられている。

役割緊張

役割緊張は、社会的に決められたある役割(例、従業員)の認識された権利、義務、および行動が別の役割(例、生徒)の権利、義務、および行動と対立する場合に経験される。がん患者の介護者が行う複数の役割は、介護者の身体的および感情的資源を巡って競合することがある。中年の介護者457人を対象にした1件の研究から、介護者が果たす社会的役割が増えるほど、介護者はストレスおよび負の影響を経験する可能性が高くなることが明らかにされた。[ 35 ]しかしながら、雇用された介護者は、職場から提供される一時休暇や雇用主および仕事仲間からの支援により便宜を得ることで、心理的資源を補充できることを認識することが重要である。[ 35 ]したがって、複数の役割が必ずしも緊張を引き起こすわけではない。

ケアの場所

がん治療は、介護者のために支援サービスを提供する機能が異なる複数の物理的な場所で提供される。したがって、ケアの場所は介護者の負担に対する危険因子と考えられる。この主張は、12人の患者と12人の介護者を対象として病院から自宅への移行において直面する難題に関する定性的面談研究の結果から裏付けられている。[ 36 ]研究者らは以下の4つの注目すべきテーマを特定した:

- 疾患およびその治療に関係した進行中の懸念。

- 時宜を得た支援の要求。

- 制御および正常性の再開。

- ケアの移行の正しい認識。

患者と介護者の組を対象にした1件の独立した研究で、自宅への移行では、症状、および予後と疾患進行に関する不確実性に対処する必要があるため、ストレスが非常に高いことが示された。[ 37 ]したがって、ケアの場所の移行を原因とする介護者の負担増加を認識し、可能な場合は、訪問看護により改善すべきである。

再入院など、ケアの場所の予定外の変更もまた、介護者への要求を増加させる。予定外の入院に対する因子について明らかにするために、129組の高齢のがん患者とその家族介護者が調査された。[ 38 ]研究者らにより、介護者の知識-多くの介入の標的とされる-よりもむしろ症状の重症度が、積極的な治療期間中の高齢のがん患者における予定外の入院を予測したことが明らかにされた。こうした結果から、症状に関する介護者の知識を増やすよりも、症状管理の介入によってストレスの高いイベントを減少させうることが示唆されている。

参考文献- Lazarus RS, Folkman S: Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co, 1984.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ream E, Pedersen VH, Oakley C, et al.: Informal carers' experiences and needs when supporting patients through chemotherapy: a mixed method study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 22 (6): 797-806, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Badr H, Herbert K, Reckson B, et al.: Unmet needs and relationship challenges of head and neck cancer patients and their spouses. J Psychosoc Oncol 34 (4): 336-46, 2016 Jul-Aug.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wheelwright S, Darlington AS, Hopkinson JB, et al.: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of quality of life in the informal carers of cancer patients with cachexia. Palliat Med 30 (2): 149-60, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Girgis A, Lambert S, Lecathelinais C: The supportive care needs survey for partners and caregivers of cancer survivors: development and psychometric evaluation. Psychooncology 20 (4): 387-93, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Oberoi DV, White V, Jefford M, et al.: Caregivers' information needs and their 'experiences of care' during treatment are associated with elevated anxiety and depression: a cross-sectional study of the caregivers of renal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 24 (10): 4177-86, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW, et al.: When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer 121 (9): 1513-9, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Chen SC, Chiou SC, Yu CJ, et al.: The unmet supportive care needs-what advanced lung cancer patients' caregivers need and related factors. Support Care Cancer 24 (7): 2999-3009, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R, et al.: Factors associated with high burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer. Cancer 120 (18): 2927-35, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Lund L, Ross L, Petersen MA, et al.: Cancer caregiving tasks and consequences and their associations with caregiver status and the caregiver's relationship to the patient: a survey. BMC Cancer 14: 541, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ge L, Mordiffi SZ: Factors Associated With Higher Caregiver Burden Among Family Caregivers of Elderly Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Cancer Nurs 40 (6): 471-478, 2017 Nov/Dec.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Stetz KM: Caregiving demands during advanced cancer. The spouse's needs. Cancer Nurs 10 (5): 260-8, 1987.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kim Y, van Ryn M, Jensen RE, et al.: Effects of gender and depressive symptoms on quality of life among colorectal and lung cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psychooncology 24 (1): 95-105, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Schrank B, Ebert-Vogel A, Amering M, et al.: Gender differences in caregiver burden and its determinants in family members of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology 25 (7): 808-14, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Scherbring M: Effect of caregiver perception of preparedness on burden in an oncology population. Oncol Nurs Forum 29 (6): E70-6, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Given CW, Stommel M, Given B, et al.: The influence of cancer patients' symptoms and functional states on patients' depression and family caregivers' reaction and depression. Health Psychol 12 (4): 277-85, 1993.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Schulz R, Beach SR: Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA 282 (23): 2215-9, 1999.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cameron JI, Franche RL, Cheung AM, et al.: Lifestyle interference and emotional distress in family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Cancer 94 (2): 521-7, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Given B, Sherwood PR: Family care for the older person with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 22 (1): 43-50, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S: Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: a meta-analysis. Gerontologist 45 (1): 90-106, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Li H: Barriers to and unmet needs for supportive services: experiences of Asian-American caregivers. J Cross Cult Gerontol 19 (3): 241-60, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ngo-Metzger Q, McCarthy EP, Burns RB, et al.: Older Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders dying of cancer use hospice less frequently than older white patients. Am J Med 115 (1): 47-53, 2003.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Guarnaccia PJ, Parra P: Ethnicity, social status, and families' experiences of caring for a mentally ill family member. Community Ment Health J 32 (3): 243-60, 1996.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cox C, Monk A: Strain among caregivers: comparing the experiences of African American and Hispanic caregivers of Alzheimer's relatives. Int J Aging Hum Dev 43 (2): 93-105, 1996.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Covinsky KE, Eng C, Lui LY, et al.: Reduced employment in caregivers of frail elders: impact of ethnicity, patient clinical characteristics, and caregiver characteristics. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56 (11): M707-13, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hayman JA, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, et al.: Estimating the cost of informal caregiving for elderly patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 19 (13): 3219-25, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- de Moor JS, Dowling EC, Ekwueme DU, et al.: Employment implications of informal cancer caregiving. J Cancer Surviv 11 (1): 48-57, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Mazanec SR, Daly BJ, Douglas SL, et al.: Work productivity and health of informal caregivers of persons with advanced cancer. Res Nurs Health 34 (6): 483-95, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, et al.: Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. CMAJ 170 (12): 1795-801, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Lambert-Obry V, Gouault-Laliberté A, Castonguay A, et al.: Real-world patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes in advanced breast cancer. Curr Oncol 25 (4): e282-e290, 2018.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Van Houtven CH, Ramsey SD, Hornbrook MC, et al.: Economic burden for informal caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer patients. Oncologist 15 (8): 883-93, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Siefert ML, Williams AL, Dowd MF, et al.: The caregiving experience in a racially diverse sample of cancer family caregivers. Cancer Nurs 31 (5): 399-407, 2008 Sep-Oct.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Li C, Zeliadt SB, Hall IJ, et al.: Burden among partner caregivers of patients diagnosed with localized prostate cancer within 1 year after diagnosis: an economic perspective. Support Care Cancer 21 (12): 3461-9, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Chen ML: The Growing Costs and Burden of Family Caregiving of Older Adults: A Review of Paid Sick Leave and Family Leave Policies. Gerontologist 56 (3): 391-6, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kim Y, Baker F, Spillers RL, et al.: Psychological adjustment of cancer caregivers with multiple roles. Psychooncology 15 (9): 795-804, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ang WH, Lang SP, Ang E, et al.: Transition journey from hospital to home in patients with cancer and their caregivers: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 24 (10): 4319-26, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Rocío L, Rojas EA, González MC, et al.: Experiences of patient-family caregiver dyads in palliative care during hospital-to-home transition process. Int J Palliat Nurs 23 (7): 332-339, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Geddie PI, Wochna Loerzel V, Norris AE: Family Caregiver Knowledge, Patient Illness Characteristics, and Unplanned Hospital Admissions in Older Adults With Cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 43 (4): 453-63, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 対処戦略および自己効力感

-

対処戦略は概念化されたものとして、プラスのまたはマイナスの結果と介護の要求が利用可能な資源を超えているという認識との関連を仲介する。ある研究者グループにより、緩和ケアを受けているがん患者の家族介護者50人に面談および調査が実施された。[ 1 ]その目的は、対処戦略と介護者における不安との関連を示すことであった。介護者には不安がよくみられた(76%)。感情ベースの対処は不安の低下に関連した一方、十分に機能していない対処は不安の増加に関連した。負担の認識もまた不安の増加に関連した。

Transactional Model of Stress and Copingで示されているように、介護者と患者は相互に結びついている。患者の対処スタイルと介護者の適応とのつながりを示す証拠が得られている。下位専門分野の緩和ケア試験からのベースラインデータに関する1件の横断研究により、治癒不能な肺がんまたは大腸がん患者の家族介護者275人における関連が確認された。[ 2 ]研究者らにより、患者が情動的サポート対処を利用するか、または予後について楽観している場合に、介護者はより強い抑うつ症状を経験することが示された。患者の情動的サポート対処は、介護者のより低い不安に関連した。

介護者と患者間のこの相関性はまた、脅威の評価(Transactional Model of Stress and Copingの第一段階)にも関与している。484組を対象にした1件の研究により、患者と介護者の症状の苦痛は自身の、および場合によってはお互いの認知的評価に影響することが実証された。[ 3 ]

参考文献- Perez-Ordóñez F, Frías-Osuna A, Romero-Rodríguez Y, et al.: Coping strategies and anxiety in caregivers of palliative cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 25 (4): 600-7, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Fishbein JN, et al.: Factors associated with depression and anxiety symptoms in family caregivers of patients with incurable cancer. Ann Oncol 27 (8): 1607-12, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ellis KR, Janevic MR, Kershaw T, et al.: The influence of dyadic symptom distress on threat appraisals and self-efficacy in advanced cancer and caregiving. Support Care Cancer 25 (1): 185-194, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 介護者の評価(スクリーニングまたは評価)

-

介護者の評価は、医療システム内のどの接触ポイントで行ってもよい。理想的には、介護者の包括的評価を以下が起こったときに実施すべきである:[ 1 ]

- 患者ががんと最初に診断されたとき。

- 患者が救急部門に搬送されたとき。

- 大きな移行が計画されたとき。

介護者が評価されるシステムでは、介護者は医療チームの貴重なメンバーとして実施者に認められる。介護者の評価により、身体的健康およびメンタルヘルスの問題の発生リスクが最も高い家族のメンバーを特定することができ、それに伴い追加のサービスを計画することができる。[ 1 ]

介護者の負担を測定するために、Zarit Burden Interview[ 2 ]や他のツール[ 3 ][ 4 ][ 5 ][ 6 ][ 7 ][ 8 ][ 9 ]を含めて、複数のツールが利用できる。介護者の負担の客観的測定は、介護の提供に費やされる時間や介護者が行う作業の実際の数といった変数で構成されている。[ 10 ][証拠レベル:II][ 11 ]客観的測定値は通常、短時間かつ容易に答えがでて、しばしば問題解決および直接介入のための明確な方向性を示す。[ 12 ]介護者の評価は、文化的に適切な方法を取り入れる必要がある。[ 13 ]

介護者の負担の測定には多くのツールがあるが、1件のレビュー[ 14 ]により、がん患者の介護者を対象とする心理測定評価に英語で記述されたツールは8つしかないことが明らかにされた。8つのうち、Caregiver Reaction Assessment(CRA)およびCaregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer(CQOLC)は、心理測定パフォーマンスが最も優れていた。また、8つのツールについて5つの包括的なテーマにおける16の概念領域が確認された。複数のツールではいくつかの領域で重複が示されたが、すべての領域を測定した単一のツールはなかった。したがって、介護者の負担の評価には、すべての領域の評価を得るために2つ以上のツールを利用することが賢明である。

参考文献- Feinberg LF: Caregiver assessment. Am J Nurs 108 (9 Suppl): 38-9, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J: Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 20 (6): 649-55, 1980.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Glajchen M, Kornblith A, Homel P, et al.: Development of a brief assessment scale for caregivers of the medically ill. J Pain Symptom Manage 29 (3): 245-54, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Weitzner MA, Jacobsen PB, Wagner H, et al.: The Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) scale: development and validation of an instrument to measure quality of life of the family caregiver of patients with cancer. Qual Life Res 8 (1-2): 55-63, 1999.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Weitzner MA, McMillan SC: The Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) Scale: revalidation in a home hospice setting. J Palliat Care 15 (2): 13-20, 1999.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, et al.: The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nurs Health 15 (4): 271-83, 1992.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Robinson BC: Validation of a Caregiver Strain Index. J Gerontol 38 (3): 344-8, 1983.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Minaya P, Baumstarck K, Berbis J, et al.: The CareGiver Oncology Quality of Life questionnaire (CarGOQoL): development and validation of an instrument to measure the quality of life of the caregivers of patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer 48 (6): 904-11, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wells DK, James K, Stewart JL, et al.: The care of my child with cancer: a new instrument to measure caregiving demand in parents of children with cancer. J Pediatr Nurs 17 (3): 201-10, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bookwala J, Schulz R: A comparison of primary stressors, secondary stressors, and depressive symptoms between elderly caregiving husbands and wives: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. Psychol Aging 15 (4): 607-16, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Gaugler JE, Hanna N, Linder J, et al.: Cancer caregiving and subjective stress: a multi-site, multi-dimensional analysis. Psychooncology 14 (9): 771-85, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Honea NJ, Brintnall R, Given B, et al.: Putting Evidence into Practice: nursing assessment and interventions to reduce family caregiver strain and burden. Clin J Oncol Nurs 12 (3): 507-16, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S: Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: a meta-analysis. Gerontologist 45 (1): 90-106, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Shilling V, Matthews L, Jenkins V, et al.: Patient-reported outcome measures for cancer caregivers: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 25 (8): 1859-76, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- がん経過の特異的段階における介護者の要求

-

がんの経験は、スクリーニングから診断および治療を経て、長期の生存または終末期のいずれかへと続くいくつかの比較的明確な段階に沿って発生するものと概念化できる。[ 1 ]こうした段階は、可能性の高い活動、目標、および患者に対して考えられる転帰に差がある。介護者と患者の相互依存を考慮すると、介護者の経験もまた一様ではないと想定するのが妥当のように思われる。

がん経過のさまざまな時点で介護者を比較した諸研究

疾患の経過を通じてまたはさまざまな病期のがん患者の介護者を直接比較した研究は不足している。あるグループにより定性研究が実施され、がん患者の介護者15人について骨髄移植前、移植中、および移植後4ヵ月経過時に面談が行われた。がんの経過を通して面談の代表的な話題はさまざまであったが、介護者の懸念に関して次の2つの一貫したテーマが明らかになった:不確実性および詳しい情報に対する要求。[ 2 ]

別の研究で、緩和ケアの後期であるか、疼痛クリニックに通院しているがん患者(著者らは治癒期と称していた)の介護者を対象にした2件の横断研究の結果が比較された。[ 3 ]著者らは、生活の質(QOL)の尺度としてHospital Anxiety and Depression Scale(HADS)またはMedical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey(SF-36)の平均スコアにおける差は認められないことを明らかにした。研究の選択基準および期間が異なるため、結果は慎重に解釈すべきである。さらに、このグループの方法は個別の介護者の経時的な意義のある変化を分かりにくくする可能性がある。

別の解析により、患者における症状の負担はコホート間で違いはなかったが、どちらの集団も脱力および疲労の測定でスコアが高かったことが示された。[ 4 ]介護者は患者に不眠が認められる場合に高い割合の抑うつを報告したが、その関連はコホート間で違いが認められなかった。ただし、研究の方法論によって、確固たる結論を引き出すには制限がある。

生存

入手可能な証拠から、満たされていない要求の割合は時間の経過とともに低下するが、少数ではあるが重要な介護者が生存期間中のがんの経験に関係した要求を経験し続けることが実証されている。

例えば、オーストラリアの1件の縦断研究は、介護者として継続的な要求があることの心理社会的、財政的、および職業的影響を追跡するようにデザインされた。[ 5 ]研究者らにより、がん診断から6ヵ月経過時の介護者547人、12ヵ月経過時の介護者519人、および24ヵ月経過時の介護者443人からのSupportive Care Needs Survey-Partners and Caregivers(SCNS-P&C)への回答が解析された。注目すべきこととして、当初の参加者547人中、12ヵ月経過時の調査を444人が完了し、24ヵ月経過時の調査を372人が完了した。

以下のように、いくつかの所見は強調する価値がある:

- 満たされていない要求を報告した介護者の割合は、6ヵ月経過時の50.2%から24ヵ月経過時には30.7%に低下した。

- ベースライン時の満たされていない要求の割合は低かったものの、5つ以上ないし10個の満たされていない要求を報告した介護者について同様の低下が示された。

- 最も差し迫った満たされていない要求は再発に関する懸念、生存者の生活のストレスの低下、および生存者の経験の理解に関係していた。

- 満たされていない要求は(一様ではないものの)介護者の幸福と負の関連がみられた。

終末期

進行がん患者の終末期の経験は、介護者への負担および結果として介護者に起こる死別後の心理的適応に影響を及ぼす。進行期卵巣がん女性の介護者を対象にした1件の縦断研究から、患者の人生の最後の1年間における介護者の経験に貴重な洞察が得られている。[ 6 ]99人の介護者が、2年間にわたって3ヵ月ごとに測定された。介護者は、予想より低い精神的および身体的QOLを報告した。苦痛と満たされていない要求の数の平均は経時的に増加した。社会的支援の認識に変化はなかった。介護者の苦痛は、楽観的なところの少なさ、満たされていない要求の高さ、および患者の死亡までの時間の短さにより予測された。患者のQOLは予測因子ではなかった。患者の人生の最後の6ヵ月間に、不良な予後に関する感情を管理すること、および仕事と介護の要求とのバランスを取ることは、介護者における満たされていない要求の高さに関係した。

ホスピスケアは、患者だけでなく介護者にも不可欠なサポートを提供できる。ある研究者グループにより、積極的な治療を受けている進行がん患者の介護者の負担およびQOLが、ホスピスケアを受けている患者の介護者の負担およびQOLと比較された。[ 7 ]この取り組みの目標は、ホスピスケア段階に特有の要求の特徴を明らかにすることであった。この研究では、精神的または感情的困難による介護の負担の認識および役割の制限の増加に差は認められなかった;しかしながら、ホスピスケアの介護者集団では身体的制限の報告が少なかった。同様に、別のグループにより、ホスピス滞在が長くなるほど、患者のQOLが良好となり、死別後の介護者の適応も良好であったことが報告された。[ 8 ]

ホスピスの利益に対する1つの考えられる説明は、終末期のケアの質の高さや患者の目標を尊重することで介護者が安心するということである。1件の研究で、進行期の肺がんまたは大腸がんにより死亡したメディケア受給者の家族のメンバー1,146人との面談が分析された。[ 9 ]結果から、ホスピスへの登録でより「素晴らしい」ケアの質が得られると家族のメンバーが報告したがことが示された。同様に、集中治療を受けたまたは登録が短かった患者は、好ましい場所で死亡したと報告される頻度が低かった。[ 10 ]

介護者はまた、患者に人工栄養と水分補給(ANH)を提供するかどうかの決定に有効に参加するためのサポートを必要とすることがある。研究者らにより、進行がん患者39人および親族30人を対象にANHに関する見解についてプロスペクティブな横断的調査が実施された。[ 11 ]最愛の人の代わりに決定する場合、ANHを受けないことを選択すると述べた親族はわずか24%であった;48%は水分補給に反対した。患者は親族よりも疼痛、激越、空腹といった不良な身体症状に関心がなかった。患者は家族のメンバーの意見を決定に重要なものとして承認した。(詳しい情報については、人生の最後の数日間に関するPDQ要約の人工的水分補給のセクションを参照のこと。)

参考文献- Levit LA, Balogh EP, Nass SJ, et al., eds.: Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2013. Also available online. Last accessed October 15, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Von Ah D, Spath M, Nielsen A, et al.: The Caregiver's Role Across the Bone Marrow Transplantation Trajectory. Cancer Nurs 39 (1): E12-9, 2016 Jan-Feb.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Grov EK, Valeberg BT: Does the cancer patient's disease stage matter? A comparative study of caregivers' mental health and health related quality of life. Palliat Support Care 10 (3): 189-96, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Valeberg BT, Grov EK: Symptoms in the cancer patient: of importance for their caregivers' quality of life and mental health? Eur J Oncol Nurs 17 (1): 46-51, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Girgis A, Lambert SD, McElduff P, et al.: Some things change, some things stay the same: a longitudinal analysis of cancer caregivers' unmet supportive care needs. Psychooncology 22 (7): 1557-64, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Butow PN, Price MA, Bell ML, et al.: Caring for women with ovarian cancer in the last year of life: a longitudinal study of caregiver quality of life, distress and unmet needs. Gynecol Oncol 132 (3): 690-7, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Spatuzzi R, Giulietti MV, Ricciuti M, et al.: Quality of life and burden in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer in active treatment settings and hospice care: A comparative study. Death Stud 41 (5): 276-283, 2017 May-Jun.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al.: Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 300 (14): 1665-73, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al.: Family Perspectives on Aggressive Cancer Care Near the End of Life. JAMA 315 (3): 284-92, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al.: Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers' mental health. J Clin Oncol 28 (29): 4457-64, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bükki J, Unterpaul T, Nübling G, et al.: Decision making at the end of life--cancer patients' and their caregivers' views on artificial nutrition and hydration. Support Care Cancer 22 (12): 3287-99, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 介護者の負担を予防、低減、または改善するための介入

-

家族等介護者の要求を扱うために、多くの種類の介入が検証されている。[ 1 ][ 2 ][ 3 ]介入では、個々の患者、介護者、または患者-介護者の組の転帰の改善に焦点が当てられている。[ 1 ]研究されている介入の種類および各介入の目標を以下に要約する。

- 認知行動療法:介護者が認識した負担および/または苦痛の感情を緩和するため、心理教育的および社会的介入を用いること。

- 補完および/または代替医療:誘導イメージ法、リフレクソロジー、回想法、マッサージ療法、および/またはヒーリングタッチにより介護者の苦痛/負担を緩和すること。

- 家族/夫婦療法:夫婦および/または家族単位の機能を改善すること。

- 対人関係療法:介護の負担の心理的結果を緩和するため、個別化されたカウンセリングを提供すること。

- 問題解決/技術習得:患者の症状を評価し管理する、介護の問題に対する解決法を確認する、がん患者の介護の役割および責任に対処する介護者の能力を高めるなど、介護技術を発展させること。

- 心理教育的:診断、予後、対処、セルフケア/在宅ケア、パートナー/家族への影響、病院でのケアまたは追跡/リハビリに関する情報など、がん患者の介護者の情報ニーズを扱うこと。[ 4 ]

- 下位専門分野の緩和ケア:介護者の懸念を直接扱い、患者の転帰を改善することで結果を改善すること。

- 支持療法:家族等介護者の感情的ニーズを扱うこと。

これらの介入の効力は入り混じっている。2~3件のメタアナリシスからの所見で、心理社会的-教育介入が介護者および患者-介護者の転帰にもたらすプラスの効果(小~中等度の効果)が確認されている。[ 5 ][ 6 ][ 7 ]しかしながら、多くの研究で小規模のサンプルサイズおよび短期の評価による制限があり、しばしば研究の焦点(患者 vs 介護者 vs 患者-介護者の組)に応じて結果が異なる。[ 1 ]本要約の次のセクションでは、メタアナリシスの結果をレビューし、続いて2~3件の個別の画期的な研究に関する情報が提供される。

メタアナリシス

1件のメタアナリシスには、1983年から2009年に発表された29件のランダム化臨床試験が含まれた。[ 6 ]この取り組みにより、心理教育的、技術習得/問題解決、治療的カウンセリングの主要な3種類の介入が確認された。著者らは概念的枠組みを用いて、転帰のデータ、ストレスと対処理論の統合、認知行動理論、生活の質(QOL)の枠組みを構成した。全体として、3つの介入はすべて、以下の転帰の改善に有望(軽度~中等度の効果)であることを示した:

- 介護の負担(11件の研究;全般的な効果の大きさ、g = 0.22)。

- 介護者の対処能力(10件の研究;全般的な効果の大きさ、最初の3ヵ月間はg = 0.47で、これは3~6ヵ月後[全般的な効果の大きさ、g = 0.20]および6ヵ月後[g = 0.35]に有意性を維持した)。

- 自己効力感(8件の研究;全般的な効果の大きさ、g = 0.25で、これは3~6ヵ月経過時[g = 0.20]および以降の追跡時に有意性を維持した)。

- QOLの側面、身体機能(7件の研究;3~6ヵ月経過時の追跡時にg = 0.22および6ヵ月経過時の追跡時にg = 0.26)、苦痛および不安(16件の研究;最初の3ヵ月間はg = 0.20)、および婚姻/家族関係(10件の研究;g = 0.20)を含むが、抑うつまたは社会的機能における有意な改善は認められなかった。

フォローアップとして、文献の系統的レビューが実施され、介護者の要求/負担を扱った49件の介入研究が確認された。[ 3 ]このレビューで8つの異なる種類の介入が指摘され、大多数の研究が心理教育的、問題解決、支持療法、および家族/夫婦療法に分類された。著者らは、認知行動療法(CBT)を用いていた研究はわずか3件だったと指摘した。しかしながら、CBTを用いていた3件の研究はすべて、家族等介護者における心理的機能の有意な改善を示した。全体として、著者らは、構造化された、統合的な、および目標指向性のプログラムは最も便益が高くなるようであると示唆した。[ 3 ]

この最初の取り組みは、家族等介護者における心理的機能を改善するためのCBTの有効性に特化して実施された統合およびメタアナリシスとともに拡大された。[ 2 ]著者らにより、CBTの小さな統計効果(Hedge's g = 0.08)が確認された;しかしながら、この有意な効果は、ランダム化比較試験のみをレビューすると消滅した。著者らは、CBTの広範な定義および家族等介護者の定義におけるばらつきによって結果が制限された可能性があると示唆した。[ 2 ]

2件の追加のレビューでは2016年までに発表された文献に焦点が当てられた。[ 8 ][ 9 ]ある研究者グループにより、がん患者の介護者におけるQOL、抑うつ、および不安を改善するため、21の心理社会的介入の系統的レビューが実施された。[ 8 ]この報告や他の報告により、複数の研究で用いられている注目に値する介入の働きが例示されており、以下に要約されている。

- 心理教育的介入:FOCUS Programは次の5つの核となる内容の分野を含む情報およびサポートプログラムである:家族との関わり(Family involvement)、楽観的な態度(Optimistic attitude)、対処の有効性(Coping effectiveness)、不確実性の低減(Uncertainty reduction)、および症状の管理(Symptom management)。この介入は複数のランダム化比較試験で検証されており、介護者のQOLにおける改善を示している。[ 10 ][ 11 ]

- 問題解決介入:COPE(創造性[Creativity]、楽観主義[Optimism]、計画[Planning]、専門家の情報[Expert Information])は、複数の研究者グループによって用いられている問題解決モデルであり、介護者のQOL[ 12 ][ 13 ]、患者症状の負担、および介護作業の負担の改善を示している。[ 12 ]このプログラムもまた、他の認知行動療法の試験と併用されており、ある程度の成功を収めている。[ 14 ]

- 心理教育療法および支持療法:CHESS(包括的健康向上支援システム[Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System])は、介護者のためのウェブベースの肺がん情報、コミュニケーション、および指導システムである。[ 15 ]このプログラムは進行非小細胞肺がん患者の家族等介護者285人において検証された。介護者は、標準ケア + (必要に応じて)インターネットにアクセス可能なノートパソコンと肺がんと支持療法のウェブサイト一覧を提供された比較群;または標準ケア + (必要に応じて)インターネットにアクセス可能なノートパソコンとCHESSの肺がんウェブサイト、「Coping with Lung Cancer: A Network of Support」へのアクセスを許可された治療群にランダムに割り付けられた。CHESSに割り付けられた介護者では、介護者の負担およびネガティブな気分の改善において軽度~中等度の有意な効果が認められた。これは、支援的な訓練プログラムにしばしば直接参加できない家族等介護者にウェブを用いて接触する良い例である。

個別の研究

本セクションでは、2~3件の個別の画期的な研究に関する情報が提供される。

研究の制限および未解決の問題の概要

入手可能な研究では多くの制限があるため、最適な介入の選択について結論を下すことはできない。顕著な制限として、以下が挙げられる:

- 面談によるセッションから電話、オンライン、またはウェブベースのソフトなど、研究間での介入の提供のばらつき。

- 家族等介護者および介入の種類の定義に関するコンセンサスの不足で、これにより研究間の比較が困難となる。

- 限られた数の場所で研究された介入の拡張可能性の潜在的な不足で、非都市部の集団および/または交通手段に懸念のある集団に介入を提供する方法という未解決の問題が残る。

- 主要なアウトカムの測定と介入の目標間の頻繁な不一致。例えば、問題解決に焦点を当てた介入ではしばしば、問題を解決するための容量の改善を評価せず、代わりに心理的適応といったより末端のアウトカムを測定する-そのため、介入効果の起因を明らかにする際に問題が持ち上がる。

- 研究参加者における介護者の負担または苦痛レベルの認識されていないばらつき。研究者らにより、苦痛の最も強い家族等介護者は試験から抜けることを自己選択する可能性が高かった;または登録した場合も、しばしば介入研究を完了できず、その後の介入の評価に影響したことが指摘された。また研究者らは、介護者の負担/苦痛のベースラインレベルの低さまたは苦痛レベルの変化を確認できない不十分な追跡のために効力はさまざまであることを示唆している。

制限は将来の研究で、以下のように扱われる:

選択された研究の結果の概要

以下の2つの表では、考えられる介入および有益性の理解に役立つ注目に値する報告が簡潔に記述されている。表1では、介入の種類別に研究が整理され、肯定的な研究と否定的な研究が強調されている。しかしながら、これまでのセクションで概説したように、方法論的な制限から比較は行えず、結論も下せていない。[ 1 ]

表1.家族等によるがん患者の介護に対する介入的アプローチ 介入の種類 肯定的な結果 否定的な結果 IC = 家族等介護者;N/A = 該当せず;QOL = 生活の質。 心理教育 介護を提供するための知識および/または能力の改善[ 16 ][ 17 ][ 18 ][ 19 ][ 20 ][ 21 ][ 22 ] 改善されない気分(不安および苦痛)[ 23 ] 心理的機能(抑うつ、不安、ストレス)の改善および介護者の負担の軽減[ 15 ][ 24 ][ 25 ][ 26 ][ 27 ] 介護者の負担における有意ではない改善[ 28 ] 患者が報告する機能的サポートおよび結婚満足度の改善[ 24 ] 改善されないQOL[ 29 ] 問題解決/能力習得 問題解決の改善[ 30 ][ 31 ][ 32 ][ 33 ][ 34 ][ 35 ] 家族等介護者の抑うつ症状の減少はみられない[ 36 ][ 37 ] 家族等介護者の信頼[ 31 ]、自己効力感[ 35 ][ 36 ][ 38 ]の改善 家族等介護者の対処または援助要請に改善はみられない[ 39 ] 心理的機能の改善(家族等介護者の抑うつ症状[ 32 ]、不安[ 34 ]、苦痛[ 35 ]、および負の影響[ 33 ]の減少) 患者のうつ症状の減少[ 32 ] 健康上のアウトカム(疲労)の改善[ 35 ] QOLの改善[ 34 ] 支持療法 サポート/知識に関する家族等介護者の認識の改善[ 40 ] 家族等介護者の心理的機能(抑うつ、不安)における有意ではない改善[ 36 ][ 41 ] 改善されない家族等介護者のQOL[ 36 ][ 42 ] 家族/夫婦療法 夫婦の機能/関係の改善[ 43 ][ 44 ] 改善されない状態不安または外傷性ストレスまたは苦痛[ 45 ] 家族等介護者が報告する介護の否定的な評価が少ない[ 10 ][ 46 ] コミュニケーション技能の改善[ 46 ] 心理的機能(家族等介護者、患者における苦痛、抑うつ、不安)の改善[ 44 ][ 47 ][ 48 ] QOLの改善[ 11 ][ 49 ] 認知行動療法 心理的機能の改善(苦痛、抑うつ症状の減少)[ 50 ][ 51 ][ 52 ] N/A がん症状の負担軽減[ 12 ] 自己効力感の改善[ 53 ] QOLの改善[ 12 ] 対人関係療法 心理的機能の改善(抑うつ、不安の減少)[ 54 ][ 55 ] N/A QOLの改善[ 55 ][ 56 ] 統合療法、代替療法、および補完療法 マッサージ:家族等介護者における抑うつ、不安、疲労の改善[ 57 ] N/A 筋力トレーニング:メンタルヘルスの改善;統計的有意性に近づいている(0.06)[ 58 ] 心配りに基づいた(mindfulness-based)ストレスの低下: -介護者の負担軽減、ただし、患者とパートナーに対する心理的苦痛の有意な低下は得られていない[ 59 ] -患者の心理的機能の有意な改善(ストレス、不安の低下)、および統計的に有意ではないものの、家族等介護者の心理的機能およびQOLの改善[ 60 ] 表2では、ほとんどの取り組みで実施されている心理教育、問題解決、および認知行動療法介入の有効性を支持する一部の調査研究が強調されている。加えて、表2ではこれらの研究のそれぞれで改善されたアウトカム(資源および/または対処)が示されている。

表2.介入およびそれにより生じたアウトカム:選択された取り組み 介入の種類/参考文献 アウトカム:改善された資源および/または対処 QOL = 生活の質。 心理教育 介護/役割の知識 問題解決 自己効力感 心理的機能 症状 QOL - Ferrell et al., 1995[ 16 ] X - Horowitz et al., 1996[ 25 ] X X - DuBenske et al., 2014[ 15 ] X - Northouse et al., 2013[ 11 ] X X - Northouse et al., 2014[ 49 ] X X X – Badr et al., 2015[ 26 ] X 問題解決 介護/役割の知識 問題解決 自己効力感 心理的機能 症状 QOL - Sahler et al., 2002[ 33 ] X X X - Nezu et al., 2003[ 32 ] X X X - Cameron et al., 2004[ 31 ] X X X - Bevans et al., 2010[ 30 ] X X - Demiris et al., 2012[ 34 ] X X X - Bevans et al., 2014[ 35 ] X X X X 認知行動療法 介護/役割の知識 問題解決 自己効力感 心理的機能 症状 QOL - Keefe et al., 2005[ 53 ] X - Carter, 2006[ 50 ] X - Cohen et al., 2006[ 51 ] X - Given et al., 2006[ 52 ] X X - McMillan et al., 2006[ 12 ] X X 参考文献- Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al.: Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer 122 (13): 1987-95, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- O'Toole MS, Zachariae R, Renna ME, et al.: Cognitive behavioral therapies for informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology 26 (4): 428-437, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Applebaum AJ, Breitbart W: Care for the cancer caregiver: a systematic review. Palliat Support Care 11 (3): 231-52, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Adams E, Boulton M, Watson E: The information needs of partners and family members of cancer patients: a systematic literature review. Patient Educ Couns 77 (2): 179-86, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Badr H, Krebs P: A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for couples coping with cancer. Psychooncology 22 (8): 1688-704, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, et al.: Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin 60 (5): 317-39, 2010 Sep-Oct.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Griffin JM, Meis LA, MacDonald R, et al.: Effectiveness of family and caregiver interventions on patient outcomes in adults with cancer: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 29 (9): 1274-82, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Fu F, Zhao H, Tong F, et al.: A Systematic Review of Psychosocial Interventions to Cancer Caregivers. Front Psychol 8: 834, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Frambes D, Given B, Lehto R, et al.: Informal Caregivers of Cancer Patients: Review of Interventions, Care Activities, and Outcomes. West J Nurs Res 40 (7): 1069-1097, 2018.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Northouse L, Kershaw T, Mood D, et al.: Effects of a family intervention on the quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psychooncology 14 (6): 478-91, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, et al.: Randomized clinical trial of a brief and extensive dyadic intervention for advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psychooncology 22 (3): 555-63, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, et al.: Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer 106 (1): 214-22, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Meyers FJ, Carducci M, Loscalzo MJ, et al.: Effects of a problem-solving intervention (COPE) on quality of life for patients with advanced cancer on clinical trials and their caregivers: simultaneous care educational intervention (SCEI): linking palliation and clinical trials. J Palliat Med 14 (4): 465-73, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, et al.: Benefits of Early Versus Delayed Palliative Care to Informal Family Caregivers of Patients With Advanced Cancer: Outcomes From the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 33 (13): 1446-52, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- DuBenske LL, Gustafson DH, Namkoong K, et al.: CHESS improves cancer caregivers' burden and mood: results of an eHealth RCT. Health Psychol 33 (10): 1261-72, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ferrell BR, Grant M, Chan J, et al.: The impact of cancer pain education on family caregivers of elderly patients. Oncol Nurs Forum 22 (8): 1211-8, 1995.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hudson P, Quinn K, Kristjanson L, et al.: Evaluation of a psycho-educational group programme for family caregivers in home-based palliative care. Palliat Med 22 (3): 270-80, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Derdiarian AK: Effects of information on recently diagnosed cancer patients' and spouses' satisfaction with care. Cancer Nurs 12 (5): 285-92, 1989.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Pasacreta JV, Barg F, Nuamah I, et al.: Participant characteristics before and 4 months after attendance at a family caregiver cancer education program. Cancer Nurs 23 (4): 295-303, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Grahn G, Danielson M: Coping with the cancer experience. II. Evaluating an education and support programme for cancer patients and their significant others. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 5 (3): 182-7, 1996.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Tsianakas V, Robert G, Richardson A, et al.: Enhancing the experience of carers in the chemotherapy outpatient setting: an exploratory randomised controlled trial to test impact, acceptability and feasibility of a complex intervention co-designed by carers and staff. Support Care Cancer 23 (10): 3069-80, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Valeberg BT, Kolstad E, Småstuen MC, et al.: The PRO-SELF pain control program improves family caregivers' knowledge of cancer pain management. Cancer Nurs 36 (6): 429-35, 2013 Nov-Dec.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cartledge Hoff A, Haaga DA: Effects of an education program on radiation oncology patients and families. J Psychosoc Oncol 23 (4): 61-79, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bultz BD, Speca M, Brasher PM, et al.: A randomized controlled trial of a brief psychoeducational support group for partners of early stage breast cancer patients. Psychooncology 9 (4): 303-13, 2000 Jul-Aug.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Horowitz S, Passik SD, Malkin MG: “In sickness and in health”: a group intervention for spouses caring for patients with brain tumors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 14 (2): 43-56, 1996.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Badr H, Smith CB, Goldstein NE, et al.: Dyadic psychosocial intervention for advanced lung cancer patients and their family caregivers: results of a randomized pilot trial. Cancer 121 (1): 150-8, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Laudenslager ML, Simoneau TL, Kilbourn K, et al.: A randomized control trial of a psychosocial intervention for caregivers of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients: effects on distress. Bone Marrow Transplant 50 (8): 1110-8, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- O'Hara RE, Hull JG, Lyons KD, et al.: Impact on caregiver burden of a patient-focused palliative care intervention for patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Support Care 8 (4): 395-404, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Perz J, Ussher JM; Australian Cancer and Sexuality Study Team: A randomized trial of a minimal intervention for sexual concerns after cancer: a comparison of self-help and professionally delivered modalities. BMC Cancer 15: 629, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bevans M, Castro K, Prince P, et al.: An individualized dyadic problem-solving education intervention for patients and family caregivers during allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a feasibility study. Cancer Nurs 33 (2): E24-32, 2010 Mar-Apr.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cameron JI, Shin JL, Williams D, et al.: A brief problem-solving intervention for family caregivers to individuals with advanced cancer. J Psychosom Res 57 (2): 137-43, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Felgoise SH, et al.: Project Genesis: assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 71 (6): 1036-48, 2003.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Sahler OJ, Varni JW, Fairclough DL, et al.: Problem-solving skills training for mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: a randomized trial. J Dev Behav Pediatr 23 (2): 77-86, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Demiris G, Parker Oliver D, Wittenberg-Lyles E, et al.: A noninferiority trial of a problem-solving intervention for hospice caregivers: in person versus videophone. J Palliat Med 15 (6): 653-60, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bevans M, Wehrlen L, Castro K, et al.: A problem-solving education intervention in caregivers and patients during allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Health Psychol 19 (5): 602-17, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hendrix C, Tepfer S, Forest S, et al.: Transitional Care Partners: a hospital-to-home support for older adults and their caregivers. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 25 (8): 407-14, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Given CW, et al.: A randomized, controlled trial of a patient/caregiver symptom control intervention: effects on depressive symptomatology of caregivers of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 30 (2): 112-22, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hendrix CC, Bailey DE, Steinhauser KE, et al.: Effects of enhanced caregiver training program on cancer caregiver's self-efficacy, preparedness, and psychological well-being. Support Care Cancer 24 (1): 327-36, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Toseland RW, Blanchard CG, McCallion P: A problem solving intervention for caregivers of cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 40 (4): 517-28, 1995.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Milberg A, Rydstrand K, Helander L, et al.: Participants' experiences of a support group intervention for family members during ongoing palliative home care. J Palliat Care 21 (4): 277-84, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kozachik SL, Given CW, Given BA, et al.: Improving depressive symptoms among caregivers of patients with cancer: results of a randomized clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum 28 (7): 1149-57, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Walsh K, Jones L, Tookman A, et al.: Reducing emotional distress in people caring for patients receiving specialist palliative care. Randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry 190: 142-7, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, et al.: A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psychooncology 18 (3): 276-83, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- McLean LM, Jones JM, Rydall AC, et al.: A couples intervention for patients facing advanced cancer and their spouse caregivers: outcomes of a pilot study. Psychooncology 17 (11): 1152-6, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Stehl ML, Kazak AE, Alderfer MA, et al.: Conducting a randomized clinical trial of an psychological intervention for parents/caregivers of children with cancer shortly after diagnosis. J Pediatr Psychol 34 (8): 803-16, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, et al.: Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer 110 (12): 2809-18, 2007.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kissane DW, McKenzie M, Bloch S, et al.: Family focused grief therapy: a randomized, controlled trial in palliative care and bereavement. Am J Psychiatry 163 (7): 1208-18, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Scott JL, Halford WK, Ward BG: United we stand? The effects of a couple-coping intervention on adjustment to early stage breast or gynecological cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol 72 (6): 1122-35, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Northouse L, Schafenacker A, Barr KL, et al.: A tailored Web-based psychoeducational intervention for cancer patients and their family caregivers. Cancer Nurs 37 (5): 321-30, 2014 Sep-Oct.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Carter PA: A brief behavioral sleep intervention for family caregivers of persons with cancer. Cancer Nurs 29 (2): 95-103, 2006 Mar-Apr.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cohen M, Kuten A: Cognitive-behavior group intervention for relatives of cancer patients: a controlled study. J Psychosom Res 61 (2): 187-96, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Given B, Given CW, Sikorskii A, et al.: The impact of providing symptom management assistance on caregiver reaction: results of a randomized trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 32 (5): 433-43, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Keefe FJ, Ahles TA, Sutton L, et al.: Partner-guided cancer pain management at the end of life: a preliminary study. J Pain Symptom Manage 29 (3): 263-72, 2005.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Badger T, Segrin C, Dorros SM, et al.: Depression and anxiety in women with breast cancer and their partners. Nurs Res 56 (1): 44-53, 2007 Jan-Feb.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Badger TA, Segrin C, Hepworth JT, et al.: Telephone-delivered health education and interpersonal counseling improve quality of life for Latinas with breast cancer and their supportive partners. Psychooncology 22 (5): 1035-42, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Badger T, Segrin C, Pasvogel A, et al.: The effect of psychosocial interventions delivered by telephone and videophone on quality of life in early-stage breast cancer survivors and their supportive partners. J Telemed Telecare 19 (5): 260-5, 2013.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Rexilius SJ, Mundt C, Erickson Megel M, et al.: Therapeutic effects of massage therapy and handling touch on caregivers of patients undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Oncol Nurs Forum 29 (3): E35-44, 2002.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Winters-Stone KM, Lyons KS, Dobek J, et al.: Benefits of partnered strength training for prostate cancer survivors and spouses: results from a randomized controlled trial of the Exercising Together project. J Cancer Surviv 10 (4): 633-44, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- van den Hurk DG, Schellekens MP, Molema J, et al.: Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for lung cancer patients and their partners: Results of a mixed methods pilot study. Palliat Med 29 (7): 652-60, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Lengacher CA, Kip KE, Barta M, et al.: A pilot study evaluating the effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on psychological status, physical status, salivary cortisol, and interleukin-6 among advanced-stage cancer patients and their caregivers. J Holist Nurs 30 (3): 170-85, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- がん経過の特異的段階における介護者への介入

-

下位専門分野の緩和ケア

本要約のこれまでのセクションで十分に示されているように、患者と介護者のメンタルヘルスおよび身体的健康と対処は相互に依存している。(詳しい情報については、本要約の二次評価:家族等介護者のための資源、がん経過の特異的段階における介護者の要求、および介護の心理的結果のセクションを参照のこと。)下位専門分野の緩和ケア介入に関する数件の試験において、介護者の転帰が特異的に標的にされ、測定された。

- Educate, Nurture, Advise Before Life Ends(ENABLE):当初は特に進行がん患者向けに開発され[ 1 ]、2015年にこの介入は家族等介護者を含め、選択されたアウトカムを改善するように特異的に拡大された。ENABLE III介入には、構造化された週1回の電話による指導3回、毎月の追跡、および死別時の電話が含まれ、COPE(創造性[Creativity]、楽観主義[Optimism]、計画[Planning]、専門家の情報[Expert Information])問題解決プログラム[ 2 ]とともに実施され、122人の家族等介護者で検証された(61人が早期介入を受け、61人が遅延介入[3ヵ月後]を受けた)。所見から、遅延介入と比較して早期介入を受けた家族等介護者では、3ヵ月経過時の抑うつスコアが低く、故人の介護者の最終的な解析における抑うつおよびストレスの負担が低かったことなど、アウトカムが良好であったことが示された。[ 3 ]

- Early Integrated Palliative Care in Advanced-Stage Lung and Gastrointestinal Cancer:介入群にランダムに割り付けられた患者および介護者は、下位専門分野の緩和ケア医師または高度医療提供者のいずれかと毎月面談するようにスケジュール設定された。[ 4 ]137人の介護者が早期緩和ケアに割り付けられ、138人が通常ケアに割り付けられた。介護者は参加するように勧誘されたが、要求はされなかった。介護者(必ずしも登録された介護者ではなかった)が参加した来院数の中央値は10回で、範囲は1~51回であった。Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale(HADS)が12週目および24週目に実施された。緩和ケア群に割り付けられた介護者では12週目(ただし24週目ではない)における抑うつ症状が少なかった;不安スコアにおける差は認められなかった。

- Early Palliative Care for Patients with Advanced Cancer:94人の介護者が介入群にランダムに割り付けられ、介入には緩和ケア施設への来院(介護者に来院は強制されなかった)および毎月の各来院の翌週に看護師による電話での連絡が含まれた。往診も利用可能であった。参加した来院数の中央値は2回で、範囲は0~8回であった;介護者の85%が少なくとも1回は来院に参加していた。緩和ケア群の介護者は、通常ケア群の介護者よりもケアに満足していたが、介護者の生活の質(QOL)における改善は認められなかった。[ 5 ]

- Palliative Care and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant:幹細胞移植のために入院中の入院患者の下位専門分野の緩和ケアへの来院が及ぼす影響の試験から、介入患者の介護者は、対照患者の介護者よりも抑うつの増加が小さかったことが実証されたが、QOLまたは不安における差はみられなかった。[ 6 ]介入では介護者に限定して焦点は当てられなかった;焦点は患者の身体的および心理的症状に当てられた。

緩和ケア/終末期

1件の系統的レビューで、終末期ケアを受けている患者について実施された14件の研究の結果が強調され、認知行動療法が最も多く(n = 6)実施されたことが示され、さまざまな研究で自己効力感の増加、心理的機能の改善、希望の増加、QOLの改善など、最も肯定的なアウトカムが実証された。[ 7 ]

参考文献- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al.: Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 302 (7): 741-9, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, et al.: Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer 106 (1): 214-22, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, et al.: Benefits of Early Versus Delayed Palliative Care to Informal Family Caregivers of Patients With Advanced Cancer: Outcomes From the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 33 (13): 1446-52, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Pirl WF, et al.: Effects of Early Integrated Palliative Care on Caregivers of Patients with Lung and Gastrointestinal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Oncologist 22 (12): 1528-1534, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- McDonald J, Swami N, Hannon B, et al.: Impact of early palliative care on caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: cluster randomised trial. Ann Oncol 28 (1): 163-168, 2017.[PUBMED Abstract]

- El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, et al.: Effect of Inpatient Palliative Care on Quality of Life 2 Weeks After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 316 (20): 2094-2103, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Chi NC, Demiris G, Lewis FM, et al.: Behavioral and Educational Interventions to Support Family Caregivers in End-of-Life Care: A Systematic Review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 33 (9): 894-908, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- 本要約の変更点(10/23/2019)

-

本要約はがんにおける家族介護者:役割と課題から改名された。

本要約は包括的に見直され、広範囲にわたって改訂された。

本要約はPDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Boardが作成と内容の更新を行っており、編集に関してはNCIから独立している。本要約は独自の文献レビューを反映しており、NCIまたはNIHの方針声明を示すものではない。PDQ要約の更新におけるPDQ編集委員会の役割および要約の方針に関する詳しい情報については、本PDQ要約についておよびPDQ® - NCI's Comprehensive Cancer Databaseを参照のこと。

- 本PDQ要約について

-

本要約の目的

医療専門家向けの本PDQがん情報要約では、がん患者の介護者に対する課題および有用な介入について包括的な、専門家の査読を経た、そして証拠に基づいた情報を提供する。本要約は、がん患者を治療する臨床家に情報を与え支援するための情報資源として作成されている。これは医療における意思決定のための公式なガイドラインまたは推奨事項を提供しているわけではない。

査読者および更新情報

本要約は編集作業において米国国立がん研究所(NCI)とは独立したPDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Boardにより定期的に見直され、随時更新される。本要約は独自の文献レビューを反映しており、NCIまたは米国国立衛生研究所(NIH)の方針声明を示すものではない。

委員会のメンバーは毎月、最近発表された記事を見直し、記事に対して以下を行うべきか決定する:

- 会議での議論、

- 本文の引用、または

- 既に引用されている既存の記事との入れ替え、または既存の記事の更新。

要約の変更は、発表された記事の証拠の強さを委員会のメンバーが評価し、記事を本要約にどのように組み入れるべきかを決定するコンセンサス過程を経て行われる。

- Larry D. Cripe, MD (Indiana University School of Medicine)

- Edward B. Perry, MD (VA Connecticut Healthcare System)

- Maria Petzel, RD, CSO, LD, CNSC, FAND (University of TX MD Anderson Cancer Center)

- Diane Von Ah, PhD, RN, FAAN (Indiana University School of Nursing)

- Amy Wachholtz, PhD, MDiv, MS, ABPP (University of Colorado)

本要約の内容に関するコメントまたは質問は、NCIウェブサイトのEmail UsからCancer.govまで送信のこと。要約に関する質問またはコメントについて委員会のメンバー個人に連絡することを禁じる。委員会のメンバーは個別の問い合わせには対応しない。

証拠レベル

本要約で引用される文献の中には証拠レベルの指定が記載されているものがある。これらの指定は、特定の介入やアプローチの使用を支持する証拠の強さを読者が査定する際、助けとなるよう意図されている。PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Boardは、証拠レベルの指定を展開する際に公式順位分類を使用している。

本要約の使用許可

PDQは登録商標である。PDQ文書の内容は本文として自由に使用できるが、完全な形で記し定期的に更新しなければ、NCI PDQがん情報要約とすることはできない。しかし、著者は“NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: 【本要約からの抜粋を含める】.”のような一文を記述してもよい。

本PDQ要約の好ましい引用は以下の通りである:

PDQ® Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board.PDQ Informal Caregivers in Cancer.Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>.Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/family-friends/family-caregivers-hp-pdq.Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>.

本要約内の画像は、PDQ要約内での使用に限って著者、イラストレーター、および/または出版社の許可を得て使用されている。PDQ情報以外での画像の使用許可は、所有者から得る必要があり、米国国立がん研究所(National Cancer Institute)が付与できるものではない。本要約内のイラストの使用に関する情報は、多くの他のがん関連画像とともにVisuals Online(2,000以上の科学画像を収蔵)で入手できる。

免責条項

これらの要約内の情報は、保険払い戻しの決定基準として使用されるべきものではない。保険の適用範囲に関する詳しい情報については、Cancer.govのManaging Cancer Careページで入手できる。

お問い合わせ

Cancer.govウェブサイトについての問い合わせまたはヘルプの利用に関する詳しい情報は、Contact Us for Helpページに掲載されている。質問はウェブサイトのEmail UsからもCancer.govに送信可能である。

画像を拡大する

画像を拡大する