ご利用について

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of melanoma. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians who care for cancer patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decision.

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

CONTENTS

- General Information About Melanoma

-

Melanoma is a malignant tumor of melanocytes, which are the cells that make the pigment melanin and are derived from the neural crest. Although most melanomas arise in the skin, they may also arise from mucosal surfaces or at other sites to which neural crest cells migrate, including the uveal tract. Uveal melanomas differ significantly from cutaneous melanoma in incidence, prognostic factors, molecular characteristics, and treatment. (Refer to the PDQ summary on Intraocular [Uveal] Melanoma Treatment for more information.)

Incidence and Mortality

Estimated new cases and deaths from melanoma in the United States in 2020:[ 1 ]

Skin cancer is the most common malignancy diagnosed in the United States, with 5.4 million cancers diagnosed among 3.3 million people in 2012.[ 1 ] Invasive melanoma represents about 1% of skin cancers but results in most deaths.[ 1 ][ 2 ] The incidence has been increasing over the past 30 years.[ 1 ] Elderly men are at highest risk; however, melanoma is the most common cancer in young adults aged 25 to 29 years and the second most common cancer in those aged 15 to 29 years.[ 3 ] Ocular melanoma is the most common cancer of the eye, with approximately 2,000 cases diagnosed annually.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for melanoma include both intrinsic (genetic and phenotype) and extrinsic (environmental or exposure) factors:

(Refer to the PDQ summaries on Skin Cancer Prevention and the Genetics of Skin Cancer for more information about risk factors.)

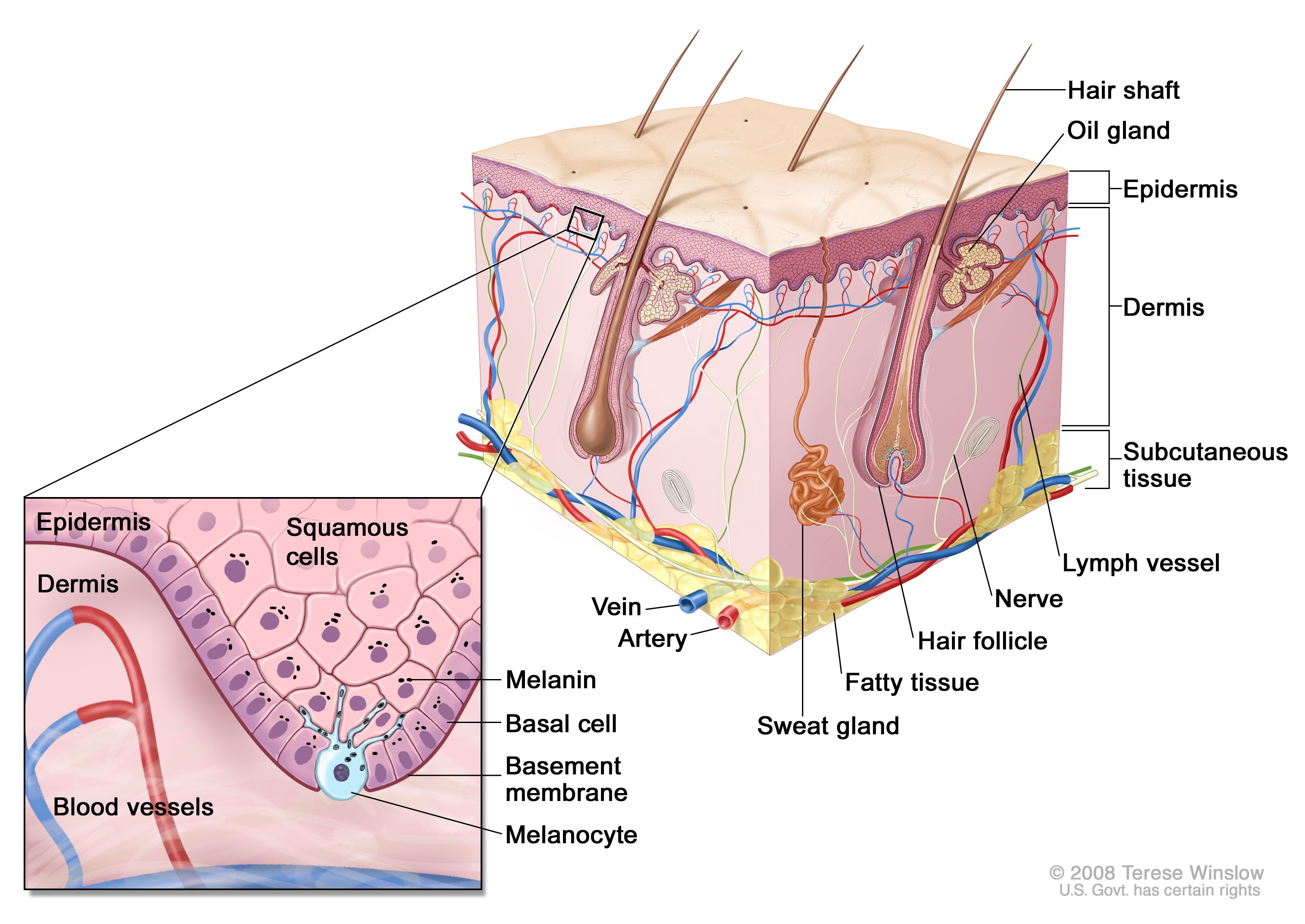

Anatomy

Schematic representation of normal skin. Melanocytes are also present in normal skin and serve as the source cell for melanoma. The relatively avascular epidermis houses both basal cell keratinocytes and squamous epithelial keratinocytes, the source cells for basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, respectively. The separation between epidermis and dermis occurs at the basement membrane zone, located just inferior to the basal cell keratinocytes. Screening

Refer to the PDQ summary on Skin Cancer Screening for more information.

Clinical Features

Melanoma occurs predominantly in adults, and more than 50% of the cases arise in apparently normal areas of the skin. Although melanoma can occur anywhere, including on mucosal surfaces and the uvea, melanoma in women occurs more commonly on the extremities, and in men it occurs most commonly on the trunk or head and neck.[ 4 ]

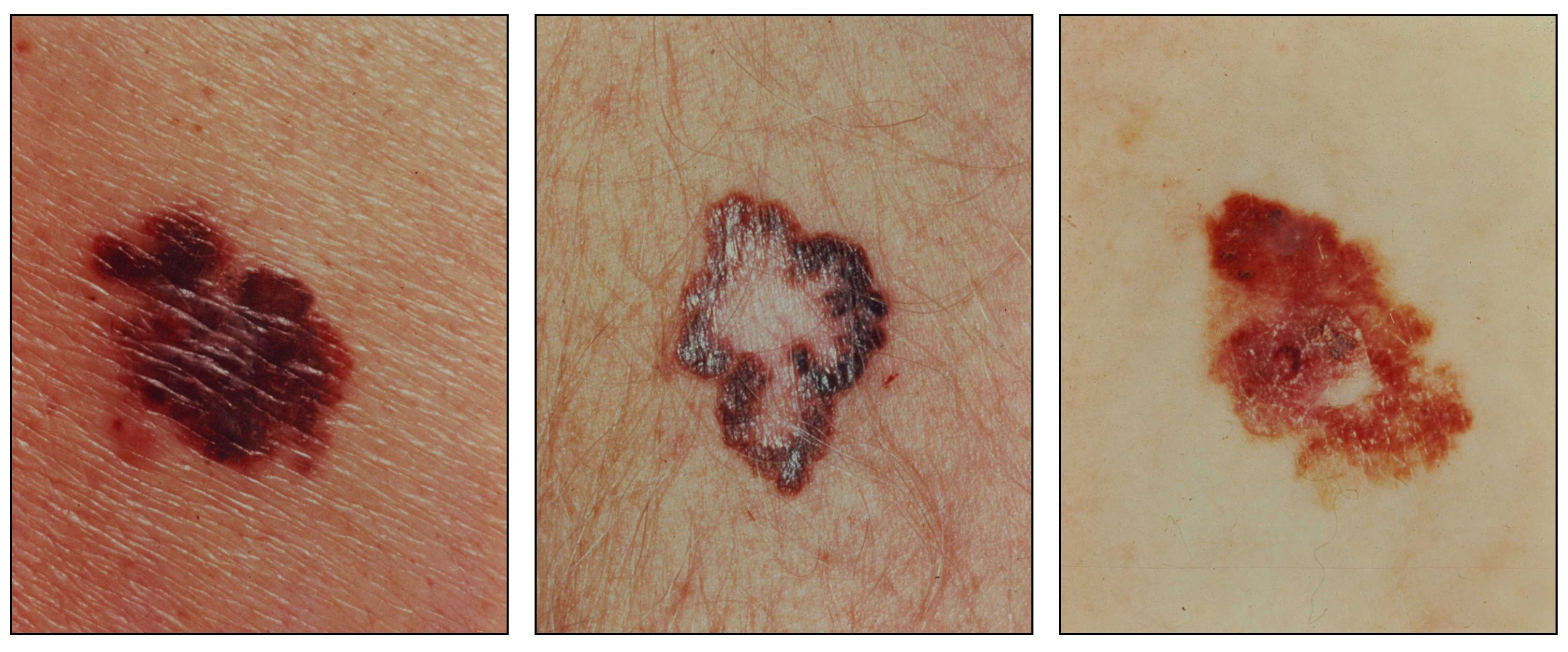

Early signs in a nevus that would suggest a malignant change include the following:

Melanomas with characteristic asymmetry, border irregularity, color variation, and large diameter. Diagnosis

A biopsy, preferably by local excision, should be performed for any suspicious lesions. Suspicious lesions should never be shaved off or cauterized. The specimens should be examined by an experienced pathologist to allow for microstaging.

Studies show that distinguishing between benign pigmented lesions and early melanomas can be difficult, and even experienced dermatopathologists can have differing opinions. To reduce the possibility of misdiagnosis for an individual patient, a second review by an independent qualified pathologist should be considered.[ 5 ][ 6 ] Agreement between pathologists in the histologic diagnosis of melanomas and benign pigmented lesions has been studied and found to be considerably variable.[ 5 ][ 6 ]

Evidence (discordance in histologic evaluation):

- One study found that there was discordance on the diagnosis of melanoma versus benign lesions in 37 of 140 cases examined by a panel of experienced dermatopathologists. For the histologic classification of cutaneous melanoma, the highest concordance was attained for Breslow thickness and presence of ulceration, while the agreement was poor for other histologic features such as Clark level of invasion, presence of regression, and lymphocytic infiltration.[ 5 ]

- In another study, 38% of cases examined by a panel of expert pathologists had two or more discordant interpretations.[ 6 ]

Prognostic Factors

Prognosis is affected by the characteristics of primary and metastatic tumors. The most important prognostic factors have been incorporated into the revised 2009 American Joint Committee on Cancer staging and include the following:[ 4 ][ 7 ][ 8 ][ 9 ]

Patients who are younger, who are female, and who have melanomas on their extremities generally have better prognoses.[ 4 ][ 7 ][ 8 ][ 9 ]

Microscopic satellites, recorded as present or absent, in stage I melanoma may be a poor prognostic histologic factor, but this is controversial.[ 10 ] The presence of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, which may be categorized as brisk, nonbrisk, or absent, is under study as a potential prognostic factor.[ 11 ]

The risk of relapse decreases substantially over time, although late relapses are not uncommon.[ 12 ][ 13 ]

Related Summaries

Other PDQ summaries containing information related to melanoma include the following:

参考文献- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2020. Atlanta, Ga: American Cancer Society, 2020. Available online. Last accessed May 12, 2020.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Melanoma. Bethesda, Md: National Library of Medicine, 2012. Available online. Last accessed January 31, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, et al., eds.: Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults 15 to 29 Years of Age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975-2000. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute, 2006. NIH Pub. No. 06-5767. Also available online. Last accessed August 16, 2019.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Slingluff CI Jr, Flaherty K, Rosenberg SA, et al.: Cutaneous melanoma. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, pp 1643-91.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Corona R, Mele A, Amini M, et al.: Interobserver variability on the histopathologic diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma and other pigmented skin lesions. J Clin Oncol 14 (4): 1218-23, 1996.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Farmer ER, Gonin R, Hanna MP: Discordance in the histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma and melanocytic nevi between expert pathologists. Hum Pathol 27 (6): 528-31, 1996.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Balch CM, Soong S, Ross MI, et al.: Long-term results of a multi-institutional randomized trial comparing prognostic factors and surgical results for intermediate thickness melanomas (1.0 to 4.0 mm). Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial. Ann Surg Oncol 7 (2): 87-97, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Manola J, Atkins M, Ibrahim J, et al.: Prognostic factors in metastatic melanoma: a pooled analysis of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trials. J Clin Oncol 18 (22): 3782-93, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al.: Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 27 (36): 6199-206, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- León P, Daly JM, Synnestvedt M, et al.: The prognostic implications of microscopic satellites in patients with clinical stage I melanoma. Arch Surg 126 (12): 1461-8, 1991.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Mihm MC, Clemente CG, Cascinelli N: Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in lymph node melanoma metastases: a histopathologic prognostic indicator and an expression of local immune response. Lab Invest 74 (1): 43-7, 1996.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Shen P, Guenther JM, Wanek LA, et al.: Can elective lymph node dissection decrease the frequency and mortality rate of late melanoma recurrences? Ann Surg Oncol 7 (2): 114-9, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Tsao H, Cosimi AB, Sober AJ: Ultra-late recurrence (15 years or longer) of cutaneous melanoma. Cancer 79 (12): 2361-70, 1997.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cellular and Molecular Classification of Melanoma

-

The descriptive terms for clinicopathologic cellular subtypes of malignant melanoma should be considered of historic interest only; they do not have independent prognostic or therapeutic significance. The cellular subtypes are the following:

- Superficial spreading.

- Nodular.

- Lentigo maligna.

- Acral lentiginous (palmar/plantar and subungual).

- Miscellaneous unusual types:

- Mucosal lentiginous (oral and genital).

- Desmoplastic.

- Verrucous.

Genomic Classification

Cutaneous melanoma

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Network performed an integrative multiplatform characterization of 333 cutaneous melanomas from 331 patients.[ 1 ] Using six types of molecular analysis at the DNA, RNA, and protein levels, the researchers identified four major genomic subtypes:

- BRAF mutant.

- RAS mutant.

- NF1 mutant.

- Triple wild-type.

Genomic subtypes may suggest drug targets and clinical trial design, as well as guide clinical decision-making for targeted therapies. Refer to Table 1 for more information.

To date, targeted therapies have demonstrated efficacy and received the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for the BRAF-mutant subtype of melanoma only. Combination therapies with a BRAF plus a MEK inhibitor have shown improvement in outcomes over a single-agent inhibitor alone; yet, virtually all patients acquire resistance to therapy and relapse. (Refer to the individual treatment sections of this summary for more information). Therefore, clinical trials remain an important option for patients with BRAF-mutant subtype, as well as other genomic subtypes of melanoma.

A variety of immunotherapies have been approved for the treatment of melanoma regardless of genetic subtype. (Refer to the individual treatment sections of this summary for more information.) The benefit of immunotherapy has not been associated with a specific mutation or molecular subtype. The TCGA analysis identified immune markers (in a subset within each molecular subtype) that were associated with improved survival and that may have implications for immunotherapy. Identification of predictive biomarkers remains an active area of research.

Table 1. Multiplatform Analysis: Mutation, Copy Number, Whole Genome, miRNA/RNA Expression, Protein Expression in Cutaneous Melanomaa Genomic Subtype % Samples With Mutation Increased Lymphocytic Infiltration (%) Clinical Management Implications for Targeted Therapy FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; WT = wild type. aPrimary melanoma with matched normal samples; N = 67 (20%). Metastatic melanoma with matched normal samples; N = 266 (80%). Matched is defined as sample from the same patient. bTriple WT was defined as a heterogeneous subgroup lacking BRAF, NRAS, HRAS, and KRAS, and NF1 mutations. cThe indications for immunotherapy are not known to be determined or limited by genomic subtype. dRisks and benefits of single versus combination therapies are detailed in Treatment Options. eResearch includes but is not limited to these examples. Clinical trials are posted on clinicaltrials.gov. fIndicated when mutation is diagnosed by an FDA-approved assay. FDA Approved Researche (single agent or in combination) BRAF mutant 52 ~ 30 BRAF inhibitorsf CDK inhibitors, PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors, ERK inhibitors, IDH1 inhibitors, EZH2 inhibitors, Aurora kinase inhibitors, ARID2 chromatin remodelers – Vemurafenib –Dabrafenib MEK inhibitors –Trametinib –Cobimetinib Combination of BRAF + MEK inhibitors –Vemurafenib + cobimetinib –Dabrafenib + trametinib RAS mutant (NRAS, HRAS, and KRAS ) 28 ~ 25 MEK inhibitors, CDK inhibitors, PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors, ERK inhibitors, IDH1 inhibitors, EZH2 inhibitors, Aurora kinase inhibitors, ARID2 chromatin remodelers NF1 mutant 14 ~ 25 PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors, ERK inhibitors, IDH1 inhibitors, EZH2 inhibitors, ARID2 chromatin remodelers Triple WTb 14.5 ~ 40 KIT-mutated/amplified CDK inhibitors (i.e., imatinib and dasatinib), MDM2/p53 interaction inhibitors, PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors, IDH1 inhibitors, EZH2 inhibitors Uveal melanoma

Uveal melanomas differ significantly from cutaneous melanomas. ln one series, 83% of 186 uveal melanomas were found to have a constitutively active somatic mutation in GNAQ or GNA11.[ 2 ][ 3 ] (Refer to the PDQ summary on Intraocular [Uveal] Melanoma Treatment for more information.)

参考文献- Cancer Genome Atlas Network: Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma. Cell 161 (7): 1681-96, 2015.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, et al.: Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue naevi. Nature 457 (7229): 599-602, 2009.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Van Raamsdonk CD, Griewank KG, Crosby MB, et al.: Mutations in GNA11 in uveal melanoma. N Engl J Med 363 (23): 2191-9, 2010.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Stage Information for Melanoma

-

Clinical staging is based on whether the tumor has spread to regional lymph nodes or distant sites. For melanoma that is clinically confined to the primary site, the chance of lymph node or systemic metastases increases as the thickness and depth of local invasion increases, which worsens the prognosis. Melanoma can spread by local extension (through lymphatics) and/or by hematogenous routes to distant sites. Any organ may be involved by metastases, but lungs and liver are common sites.

The microstage of malignant melanoma is determined on histologic examination by the vertical thickness of the lesion in millimeters (Breslow classification) and/or the anatomic level of local invasion (Clark classification). The Breslow thickness is more reproducible and more accurately predicts subsequent behavior of malignant melanoma in lesions thicker than 1.5 mm and should always be reported.

Accurate microstaging of the primary tumor requires careful histologic evaluation of the entire specimen by an experienced pathologist.

Clark Classification (Level of Invasion)

Table 2. Clark Classification (Level of Invasion) Level of Invasion Description Level I Lesions involving only the epidermis (in situ melanoma); not an invasive lesion. Level II Invasion of the papillary dermis; does not reach the papillary-reticular dermal interface. Level III Invasion fills and expands the papillary dermis but does not penetrate the reticular dermis. Level IV Invasion into the reticular dermis but not into the subcutaneous tissue. Level V Invasion through the reticular dermis into the subcutaneous tissue. AJCC Stage Groupings and TNM Definitions

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has designated staging by TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) classification to define melanoma.[ 1 ]

Cancers staged using this staging system include cutaneous melanoma. Cancers not staged using this system include melanoma of the conjunctiva, melanoma of the uvea, mucosal melanoma arising in the head and neck, mucosal melanoma of the urethra, vagina, rectum, and anus, Merkel cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma.[ 1 ]

AJCC Prognostic Stage Groups-Clinical (cTNM)

Table 3. Definition of cTNM Stage 0a Stage TNM T Category (Thickness/Ulceration Status) N Category (No. of Tumor-Involved Regional Lymph Nodes/Presence of In-Transit, Satellite, and/or Microsatellite Metastases) M Category (Anatomic Site/LDH Level) T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; c = clinical; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; No. = number. aAdapted from AJCC: Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 563–85. bThickness and ulceration status not applicable. 0 Tis, N0, M0 Tis = Melanoma in situ.b N0 = No regional metastases detected. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. Table 4. Definition of cTNM Stages IA and IBa Stage TNM T Category (Thickness/Ulceration Status) N Category (No. of Tumor-Involved Regional Lymph Nodes/Presence of In-Transit, Satellite, and/or Microsatellite Metastases) M Category (Anatomic Site/LDH Level) T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; c = clinical; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; No. = number. aAdapted from AJCC: Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 563–85. IA T1a, N0, M0 T1a = <0.8 mm/without ulceration. N0 = No regional metastases detected. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. IB T1b, N0, M0 T1b = <0.8 mm with ulceration; 0.8–1.0 mm with or without ulceration. N0 = No regional metastases detected. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. T2a, N0, M0 T2a = >1.0–2.0 mm/without ulceration. N0 = No regional metastases detected. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. Table 5. Definition of cTNM Stages IIA, IIB, and IICa Stage TNM T Category (Thickness/Ulceration Status) N Category (No. of Tumor-Involved Regional Lymph Nodes/Presence of In-Transit, Satellite, and/or Microsatellite Metastases) M Category (Anatomic Site/LDH Level) T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; c = clinical; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; No. = number. aAdapted from AJCC: Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 563–85. IIA T2b, N0, M0 T2b = >1.0–2.0 mm/with ulceration. N0 = No regional metastases detected. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. T3a, N0, M0 T3a = >2.0–4.0 mm/without ulceration. N0 = No regional metastases detected. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. IIB T3b, N0, M0 T3b = >2.0–4.0 mm/with ulceration. N0 = No regional metastases detected. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. T4a, N0, M0 T4a = >4.0 mm/without ulceration. N0 = No regional metastases detected. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. IIC T4b, N0, M0 T4b = >4.0 mm/with ulceration. N0 = No regional metastases detected. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. Table 6. Definition of cTNM Stage IIIa Stage TNM T Category (Thickness/Ulceration Status) N Category (No. of Tumor-Involved Regional Lymph Nodes/Presence of In-Transit, Satellite, and/or Microsatellite Metastases) M Category (Anatomic Site/LDH) T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; c = clinical; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; No. = number. aAdapted from AJCC: Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 563–85. bFor example, diagnosis by curettage. cFor example, unknown primary or completely regressed melanoma. dThickness and ulceration status not applicable. eDetected by sentinel lymph node biopsy. III Any T, Tis, ≥N1, M0 TX = Primary tumor cannot be assessed.b,d N1a = One clinically occult nodee /in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. T0 = No evidence of primary tumor.c,d Tis = Melanoma in situ.d N1b = One clinically detected node/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. T1a = <0.8 mm/without ulceration. N1c = No regional lymph node disease/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. T1b = <0.8 mm with ulceration; 0.8–1.0 mm with or without ulceration. N2a = Two or three clinically occult nodese/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. T2a = >1.0–2.0 mm/without ulceration. N2b = Two or three nodes at least one of which was clinically detected/in-transit, satellite, and or microsatellite metastases not present. T2b = >1.0–2.0 mm/with ulceration. N2c = One clinically occult or clinically detected node/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. T3a = >2.0–4.0 mm/without ulceration. N3a = Four or more clinically occult nodese/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. T3b = >2.0–4.0 mm/with ulceration. N3b = Four or more nodes, at least one of which was clinically detected, or presence of any number of matted nodes/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. T4a = >4.0 mm/without ulceration. N3c = Two or more clinically occult or clinically detected nodes and/or presence of any number of matted nodes/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. T4b = >4.0 mm/with ulceration. Table 7. Definition of cTNM Stage IVa Stage TNM T Category (Thickness/Ulceration Status) N Category (No. of Tumor-Involved Regional Lymph Nodes/Presence of In-Transit, Satellite, and/or Microsatellite Metastases) M Category (Anatomic Site/LDH Level) T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; c = clinical; CNS = central nervous system; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; No. = number. aAdapted from AJCC: Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 563–85. bFor example, sentinel lymph node biopsy not performed, regional nodes previously removed for another reason. (Exception: pathological N category is not required for T1 melanomas, use cN). IV Any T, Any N, M1 Any T = See Table 6 for description. NX = Regional nodes not assessed;b N0 = No regional metastases; ≥N1 = See Table 6 for description. M1 = Evidence of distant metastasis. –M1a = Distant metastasis to skin, soft tissue including muscle, and/or nonregional lymph nodes [M1a(0) = LDH not elevated; M1a(1) = LDH elevated]. –M1b = Distant metastasis to lung with or without M1a sites of disease [M1b(0) = LDH not elevated; M1b(1) = LDH elevated]. –M1c = Distant metastasis to non-CNS visceral sites with or without M1a or M1b sites of disease [M1c(0) = LDH not elevated; OR M1c(1) = LDH elevated]. –M1d = Distant metastasis to CNS with or without M1a, M1b, or M1c sites of disease [M1d(0) = LDH not elevated; M1d(1) = LDH elevated]. AJCC Prognostic Stage Groups-Pathological (pTNM)

Table 11. Definition of pTNM Stages IIIA, IIIB, IIIC, and IIIDa Stage TNM T Category (Thickness/Ulceration Status) N Category (No. of Tumor-Involved Regional Lymph Nodes/Presence of In-Transit, Satellite, and/or Microsatellite Metastases) M Category (Anatomic Site/LDH Level) T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; No. = number; p = pathological. aAdapted from AJCC: Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 563–85. bDetected by sentinel lymph node biopsy. cFor example, unknown primary or completely regressed melanoma. dThickness and ulceration status not applicable. IIIA T1a/b–T2a, N1a or N2a, M0 T1a = <0.8 mm/without ulceration/T1b = <0.8 mm with ulceration; 0.8–1.0 mm with or without ulceration. N1a = One clinically occult nodeb/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present; OR N2a = Two or three clinically occult nodesb/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. T2a = >1.0–2.0 mm/without ulceration. IIIB T0, N1b, N1c, M0 T0 = No evidence of primary tumor.c,d N1b = One clinically detected node/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. N1c = No regional lymph node disease/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. T1a/b–T2a, N1b/c or N2b, M0 T1a = <0.8 mm/without ulceration/T1b <0.8 mm with ulceration; 0.8–1.0 mm with or without ulceration. N1b = One clinically detected node/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present;/N1c = No regional lymph node disease/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present; OR M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. T2a = >1.0–2.0 mm/without ulceration. N2b = Two or three nodes at least one of which was clinically detected/in-transit, satellite, and or microsatellite metastases not present. T2b/T3a, N1a–N2b, M0 T2b = >1.0–2.0 mm/with ulceration/T3a = >2.0–4.0 mm/without ulceration. N1a = One clinically occult nodeb/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. N1b = One clinically detected node/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. N1c = No regional lymph node disease/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. N2a = Two or three clinically occult nodesb/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. N2b = Two or three nodes, at least one of which was clinically detected/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. IIIC T0, N2b, N2c, N3b, or N3c, M0 T0 = No evidence of primary tumor.c,d N2b = Two or three nodes, at least one of which was clinically detected/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. N2c = One clinically occult or clinically detected node/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. N3b = Four or more nodes, at least one of which was clinically detected, or presence of any number of matted nodes/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present; OR N3c = Two or more clinically occult or clinically detected nodes and/or presence of any number of matted nodes/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. T1a–T3a, N2c or N3a/b/c, M0 T1a = <0.8 mm/without ulceration/T1b = <0.8 mm with ulceration; 0.8–1.0 mm with or without ulceration. N2c = One clinically occult or clinically detected node/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present; OR M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. T2a = >1.0–2.0 mm/without ulceration. T2b = >1.0–2.0 mm/with ulceration. N3a = Four or more clinically occult nodesb/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. N3b = Four or more nodes, at least one of which was clinically detected, or presence of any number of matted nodes/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. T3a = >2.0–4.0 mm/without ulceration. N3c = Two or more clinically occult or clinically detected nodes and/or presence of any number of matted nodes/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. T3b/T4a, Any N ≥N1, M0 T3b = >2.0–4.0 mm/with ulceration/T4a = >4.0 mm/without ulceration. N1a = One clinically occult nodeb/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. N1b = One clinically detected node/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. N1c = No regional lymph node disease/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. N2a = Two or three clinically occult nodesb/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. N2b = Two or three nodes, at least one of which was clinically detected/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. N2c = One clinically occult or clinically detected node/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. N3a = Four or more clinically occult nodesb/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. N3b = Four or more nodes, at least one of which was clinically detected, or presence of any number of matted nodes/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. N3c = Two or more clinically occult or clinically detected nodes and/or presence of any number of matted nodes/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. T4b, N1a–N2c, M0 T4b = >4.0 mm/with ulceration. N1a = One clinically occult nodeb/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. N1b = One clinically detected node/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. N1c = No regional lymph node disease/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. N2a = Two or three clinically occult nodesb/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. N2b = Two or three nodes, at least one of which was clinically detected/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. N2c = One clinically occult or clinically detected node/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. IIID T4b, N3a/b/c, M0 T4b = >4.0 mm/with ulceration. N3a = Four or more clinically occult nodesb/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. M0 = No evidence of distant metastasis. N3b = Four or more nodes, at least one of which was clinically detected, or presence of any number of matted nodes/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases not present. N3c = Two or more clinically occult or clinically detected nodes and/or presence of any number of matted nodes/in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases present. Table 12. Definition of pTNM Stage IVa Stage TNM T Category (Thickness/Ulceration Status) N Category (No. of Tumor-Involved Regional Lymph Nodes/Presence of In-Transit, Satellite, and/or Microsatellite Metastases) M Category (Anatomic Site/LDH Level) Illustration T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; cN = clinical N; CNS = central nervous system; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; No. = number; p = pathological. aAdapted from AJCC: Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 563–85. bFor example, sentinel lymph node biopsy not performed, regional nodes previously removed for another reason. (Exception: pathological N category is not required for T1 melanomas, use cN). cPathological stage 0 (melanoma in situ) and T1 do not require pathological evaluation of lymph nodes to complete pathological staging; use cN information to assign their pathological stage. dThickness and ulceration status not applicable. IV Any T, Tis, Any N, M1 Any T = See Table 6 for description. NX = Regional nodes not assessed;d N0 = No regional metastases; ≥N1 = See Table 6 for description. M1 = Evidence of distant metastasis.

Tis = Melanoma in situ.b,c –M1a = Distant metastasis to skin, soft tissue including muscle, and/or nonregional lymph nodes [M1a(0) = LDH not elevated; M1a(1) = LDH elevated]. –M1b = Distant metastasis to lung with or without M1a sites of disease [M1b(0) = LDH not elevated; M1b(1) = LDH elevated]. –M1c - Distant metastasis to non-CNS visceral sites with or without M1a or M1b sites of disease [M1c(0) = LDH not elevated; M1c(1) = LDH elevated]. –M1d = Distant metastasis to CNS with or without M1a, M1b, or M1c sites of disease [M1d(0) = LDH not elevated; M1d(1) = LDH elevated]. 参考文献- Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 563–85.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Treatment Option Overview for Melanoma

-

Table 13. Standard Treatment Options for Melanoma Standard Treatment Options aClinical trials are an important option for patients with all stages of melanoma because advances in understanding the aberrant molecular and biologic pathways have led to rapid drug development. Standard treatment options are available in many clinical trials. Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI website. Stage 0 melanoma Excision Stage I melanoma Excision +/− lymph node management Stage II melanoma Excision +/− lymph node management Resectable Stage III melanoma Excision +/− lymph node management Unresectable Stage III, Stage IV, and Recurrent melanoma Intralesional therapy Immunotherapy Signal-transduction inhibitors Chemotherapy Palliative local therapy Excision

Surgical excision remains the primary modality for treating melanoma. Cutaneous melanomas that have not spread beyond the site at which they developed are highly curable. The treatment for localized melanoma is surgical excision with margins proportional to the microstage of the primary lesion.

Lymph node management

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB)

Lymphatic mapping and SLNB can be considered to assess the presence of occult metastasis in the regional lymph nodes of patients with primary tumors larger than 1 to 4 mm, potentially identifying individuals who may be spared the morbidity of regional lymph node dissections and individuals who may benefit from adjuvant therapy.[ 1 ][ 2 ][ 3 ][ 4 ][ 5 ][ 6 ]

To ensure accurate identification of the sentinel lymph node, lymphatic mapping and removal of the SLN should precede wide excision of the primary melanoma.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the diagnostic accuracy of SLNB, with false-negative rates of 0% to 2%.[ 1 ][ 6 ][ 7 ][ 8 ][ 9 ][ 10 ][ 11 ] If metastatic melanoma is detected, a complete regional lymphadenectomy can be performed in a second procedure.

Complete lymph node dissection (CLND)

Patients can be considered for CLND if the sentinel node(s) is microscopically or macroscopically positive for regional control or considered for entry into the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial II (NCT00297895) to determine whether CLND affects survival. SLNB should be performed before wide excision of the primary melanoma to ensure accurate lymphatic mapping.

Adjuvant Therapy

Adjuvant therapy options are expanding for patients at high risk of recurrence after complete resection, with data still emerging on optimal therapy. Ipilimumab was the first checkpoint inhibitor to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as adjuvant therapy, and has demonstrated improved overall survival (OS) at 10 mg/kg (ipi10) compared with placebo (EORTC 18071 [NCT00636168]).[ 12 ] However, ipilimumab has significant toxicity at this dose. The North American Intergroup Trial E1609 (NCT01274338) tested ipi10 and ipilimumab at a lower dose of 3 mg/kg (ipi3) (approved for metastatic melanoma) and compared them with high-dose interferon (HDI). Ipi3 showed a significant improvement in OS whereas ipi10 did not.[ 13 ] These data remove support for HDI as adjuvant treatment of melanoma. As newer checkpoint inhibitors emerge, the role of ipi3 remains to be defined.

Large randomized trials with the newer checkpoint inhibitors (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) and with combination signal transduction inhibitors (dabrafenib plus trametinib) demonstrate a clinically significant impact on relapse-free survival (RFS) with less toxicity than with ipilimumab. CheckMate 238 (NCT02388906) compared nivolumab with ipi10 and nivolumab was superior in RFS and the safety profile.[ 14 ] Data on OS are maturing for all of these trials.

The benefit of immunotherapy with ipilimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab has been seen regardless of programmed death-ligand 1 expression or BRAF mutations. Combination signal transduction inhibitor therapy is an additional option for patients with BRAF mutations.

Participation in clinical trials designed to identify treatments that will further extend RFS and OS with less toxicity and shorter treatment schedules is an important option for all patients.

Limb Perfusion

A completed, multicenter, phase III randomized trial (SWOG-8593) of patients with high-risk primary stage I limb melanoma did not show a disease-free survival or OS benefit from isolated limb perfusion with melphalan, when compared with surgery alone.[ 5 ]

Systematic Treatment for Unresectable Stage III, Stage IV, and Recurrent Disease

Although melanoma that has spread to distant sites is rarely curable, treatment options are rapidly expanding. Two approaches—checkpoint inhibition and targeting the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway—have demonstrated improvement in OS in randomized trials in comparison to dacarbazine (DTIC). Although none appear to be curative when used as single agents, early data of combinations are promising. Given the rapid development of new agents and combinations, patients and their physicians are encouraged to consider treatment in a clinical trial for initial treatment and at the time of progression.

Immunotherapy

Checkpoint inhibitors

Three checkpoint inhibitors—pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and ipilimumab—are now approved by the FDA. Each has demonstrated the ability to impact OS against different comparators in unresectable or advanced disease. (Refer to the Pembrolizumab, the Nivolumab, and the Ipilimumab sections in the Unresectable Stage III, Stage IV, and Recurrent Melanoma Treatment section of this summary for more information.) Multiple phase III trials are in progress to determine optimal sequencing of immunotherapies, immunotherapy with targeted therapy, and whether combinations of immunotherapies or immunotherapy plus targeted therapy are superior for increasing OS.

Interleukin-2 (IL-2)

IL-2 was approved by the FDA in 1998 because of durable complete response (CR) rates in a minority of patients (6%–7%) with previously treated metastatic melanoma in eight phase I and II studies. Phase III trials comparing high-dose IL-2 with other treatments and providing an assessment of relative impact on OS have not been conducted.

Signal-transduction inhibitors

Studies to date indicate that both BRAF and MEK inhibitors can significantly impact the natural history of melanoma, although they do not appear to be curative as single agents.

BRAF inhibitors

Vemurafenib

Vemurafenib, approved by the FDA in 2011, has demonstrated an improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) and OS in patients with unresectable or advanced disease. Vemurafenib is an orally available, small-molecule, selective BRAF V600E kinase inhibitor, and its indication is limited to patients with a demonstrated BRAF V600E mutation by an FDA-approved test.[ 11 ]

Dabrafenib

Dabrafenib, an orally available, small-molecule, selective BRAF inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2013, showed improvement in PFS when compared with DTIC in an international, multicenter trial (BREAK-3 [NCT01227889]).

MEK inhibitors

Trametinib

Trametinib is an orally available, small-molecule, selective inhibitor of MEK1 and MEK2 that was approved by the FDA in 2013 for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E or K mutations. Trametinib demonstrated improved PFS over DTIC.

Cobimetinib

Cobimetinib is an orally available, small-molecule, selective MEK inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2015 for use in combination with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib. (Refer to the Combination signal-transduction inhibitor therapy section of this summary for more information.)

c-KIT inhibitors

Early data suggest that mucosal or acral melanomas with activating mutations or amplifications in c-KIT may be sensitive to a variety of c-KIT inhibitors.[ 15 ][ 16 ][ 17 ] Phase II and phase III trials are available for patients with unresectable stage III or stage IV melanoma harboring the c-KIT mutation.

Combination signal-transduction inhibitor therapy

In 2014, the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib received accelerated approval from the FDA for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanomas that carry the BRAF V600E or V600K mutation. The combination demonstrated improved durable response rates over single-agent dabrafenib. Full approval is pending completion of ongoing clinical trials and demonstration of clinical benefit on OS.

In 2015, the combination of vemurafenib and cobimetinib was also approved by the FDA for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanomas that carry the BRAF V600E or V600 K mutation. Published phase III data support improved PFS using another combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors versus BRAF inhibitor plus placebo—dabrafenib plus trametinib compared with dabrafenib plus placebo. OS data are immature.

Chemotherapy

DTIC

DTIC was approved in 1970 on the basis of overall response rates. Phase III trials indicate an overall response rate of 10% to 20%, with rare CRs observed. An impact on OS has not been demonstrated in randomized trials.[ 18 ][ 19 ][ 20 ][ 21 ] When used as a control arm for recent registration trials of ipilimumab and vemurafenib in previously untreated patients with metastatic melanoma, DTIC was shown to be inferior for OS.

Temozolomide

Temozolomide, an oral alkylating agent, appeared to be similar to intravenous DTIC in a randomized phase III trial with a primary endpoint of OS; however, because the trial was designed to demonstrate the superiority of temozolomide, which was not achieved, the trial was left with a sample size that was inadequate to provide statistical proof of noninferiority.[ 19 ]

参考文献- Shen P, Wanek LA, Morton DL: Is adjuvant radiotherapy necessary after positive lymph node dissection in head and neck melanomas? Ann Surg Oncol 7 (8): 554-9; discussion 560-1, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hochwald SN, Coit DG: Role of elective lymph node dissection in melanoma. Semin Surg Oncol 14 (4): 276-82, 1998.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wagner JD, Gordon MS, Chuang TY, et al.: Current therapy of cutaneous melanoma. Plast Reconstr Surg 105 (5): 1774-99; quiz 1800-1, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cascinelli N, Morabito A, Santinami M, et al.: Immediate or delayed dissection of regional nodes in patients with melanoma of the trunk: a randomised trial. WHO Melanoma Programme. Lancet 351 (9105): 793-6, 1998.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Koops HS, Vaglini M, Suciu S, et al.: Prophylactic isolated limb perfusion for localized, high-risk limb melanoma: results of a multicenter randomized phase III trial. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Malignant Melanoma Cooperative Group Protocol 18832, the World Health Organization Melanoma Program Trial 15, and the North American Perfusion Group Southwest Oncology Group-8593. J Clin Oncol 16 (9): 2906-12, 1998.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Wong SL, Balch CM, Hurley P, et al.: Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology joint clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 30 (23): 2912-8, 2012.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kirkwood JM, Strawderman MH, Ernstoff MS, et al.: Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial EST 1684. J Clin Oncol 14 (1): 7-17, 1996.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Kirkwood JM, Ibrahim JG, Sondak VK, et al.: High- and low-dose interferon alfa-2b in high-risk melanoma: first analysis of intergroup trial E1690/S9111/C9190. J Clin Oncol 18 (12): 2444-58, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Eggermont AM, Suciu S, Santinami M, et al.: Adjuvant therapy with pegylated interferon alfa-2b versus observation alone in resected stage III melanoma: final results of EORTC 18991, a randomised phase III trial. Lancet 372 (9633): 117-26, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hancock BW, Wheatley K, Harris S, et al.: Adjuvant interferon in high-risk melanoma: the AIM HIGH Study--United Kingdom Coordinating Committee on Cancer Research randomized study of adjuvant low-dose extended-duration interferon Alfa-2a in high-risk resected malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol 22 (1): 53-61, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al.: Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med 364 (26): 2507-16, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, et al.: Prolonged Survival in Stage III Melanoma with Ipilimumab Adjuvant Therapy. N Engl J Med 375 (19): 1845-1855, 2016.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Tarhini AA, Lee SJ, Hodi FS, et al.: Phase III Study of Adjuvant Ipilimumab (3 or 10 mg/kg) Versus High-Dose Interferon Alfa-2b for Resected High-Risk Melanoma: North American Intergroup E1609. J Clin Oncol 38 (6): 567-575, 2020.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Leo F, Cagini L, Rocmans P, et al.: Lung metastases from melanoma: when is surgical treatment warranted? Br J Cancer 83 (5): 569-72, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hodi FS, Friedlander P, Corless CL, et al.: Major response to imatinib mesylate in KIT-mutated melanoma. J Clin Oncol 26 (12): 2046-51, 2008.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Guo J, Si L, Kong Y, et al.: Phase II, open-label, single-arm trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring c-Kit mutation or amplification. J Clin Oncol 29 (21): 2904-9, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Carvajal RD, Antonescu CR, Wolchok JD, et al.: KIT as a therapeutic target in metastatic melanoma. JAMA 305 (22): 2327-34, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Chapman PB, Einhorn LH, Meyers ML, et al.: Phase III multicenter randomized trial of the Dartmouth regimen versus dacarbazine in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 17 (9): 2745-51, 1999.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Middleton MR, Grob JJ, Aaronson N, et al.: Randomized phase III study of temozolomide versus dacarbazine in the treatment of patients with advanced metastatic malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol 18 (1): 158-66, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Avril MF, Aamdal S, Grob JJ, et al.: Fotemustine compared with dacarbazine in patients with disseminated malignant melanoma: a phase III study. J Clin Oncol 22 (6): 1118-25, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, et al.: Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 364 (26): 2517-26, 2011.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Ollila DW, Hsueh EC, Stern SL, et al.: Metastasectomy for recurrent stage IV melanoma. J Surg Oncol 71 (4): 209-13, 1999.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Gutman H, Hess KR, Kokotsakis JA, et al.: Surgery for abdominal metastases of cutaneous melanoma. World J Surg 25 (6): 750-8, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Stage 0 Melanoma Treatment

-

Standard Treatment Options for Stage 0 Melanoma

Standard treatment options for stage 0 melanoma include the following:

Excision

Patients with stage 0 disease may be treated by excision with minimal, but microscopically free, margins.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

- Stage I Melanoma Treatment

-

Standard Treatment Options for Stage I Melanoma

Standard treatment options for stage I melanoma include the following:

- Excision with or without lymph node management.

Excision

Evidence suggests that lesions no thicker than 2 mm may be treated conservatively with radial excision margins of 1 cm.

Depending on the location of the melanoma, most patients can now have the excision performed on an outpatient basis.

Evidence (excision):

- A randomized trial compared narrow margins (1 cm) with wide margins (≥3 cm) in patients with melanomas no thicker than 2 mm.[

1

][

2

][Level of evidence: 1iiA]

- No difference was observed between the two groups in the development of metastatic disease, disease-free survival (DFS), or overall survival (OS).

- Two other randomized trials compared 2-cm margins with wider margins (4 cm or 5 cm).[

3

][

4

][Level of evidence:1iiA]

- No statistically significant difference in local recurrence, distant metastasis, or OS was found; the median follow-up was at least 10 years for both trials.

- In the Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial, the reduction in margins from 4 cm to 2 cm

was associated with both of the following:[

5

][Level of evidence: 1iiA]

- A statistically significant reduction in the need for skin grafting (from 46% to 11%; P < .001).

- A reduction in the length of hospital stay.

- A multicenter, phase III randomized trial (SWOG-8593) of patients with high-risk stage I primary limb melanoma did not show a DFS or OS benefit from isolated limb perfusion with melphalan, when compared with surgery alone.[ 6 ][ 7 ]

Lymph node management

Elective regional lymph node dissection is of no proven benefit for patients with stage I melanoma.[ 8 ]

Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) for patients who have tumors of intermediate thickness and/or ulcerated tumors may identify individuals with occult nodal disease. These patients may benefit from regional lymphadenectomy and adjuvant therapy.[ 6 ][ 9 ][ 10 ][ 11 ]

Evidence (immediate lymphadenectomy vs. observation with delayed lymphadenectomy):

- The International Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-1 [JWCI-MORD-MSLT-1193]) included 1,269 patients with intermediate-thickness (defined as 1.2 mm–3.5 mm in this study) primary melanomas.[

12

][Level of evidence: 1iiB]

- There was no melanoma-specific survival advantage (primary endpoint) for patients randomly assigned to undergo wide excision plus SLNB, followed by immediate complete lymphadenectomy for node positivity versus nodal observation and delayed lymphadenectomy for subsequent nodal recurrence at a median of 59.8 months.

- This trial was not designed to detect a difference in the impact of lymphadenectomy in patients with microscopic lymph node involvement.

- The Sunbelt Melanoma Trial (UAB-9735 [NCT00004196]) was a phase III trial to determine the effects of lymphadenectomy with or without adjuvant high-dose interferon alpha-2b versus observation on DFS and OS in patients with submicroscopic sentinel lymph node (SLN) metastasis detected only by the polymerase chain reaction assay (i.e., SLN negative by histology and immunohistochemistry).

- No survival data have been reported from this study.

Treatment Options Under Clinical Evaluation for Stage I Melanoma

Treatment options under clinical evaluation for patients with stage I melanoma include the following:

- Clinical trials evaluating new techniques to detect submicroscopic SLN metastasis. Because of the higher rate of treatment failure in the subset of clinical stage I patients with occult nodal disease, clinical trials have evaluated new techniques to detect submicroscopic SLN metastasis to identify patients who may benefit from regional lymphadenectomy with or without adjuvant therapy.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

参考文献- Veronesi U, Cascinelli N: Narrow excision (1-cm margin). A safe procedure for thin cutaneous melanoma. Arch Surg 126 (4): 438-41, 1991.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Adamus J, et al.: Thin stage I primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Comparison of excision with margins of 1 or 3 cm. N Engl J Med 318 (18): 1159-62, 1988.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cohn-Cedermark G, Rutqvist LE, Andersson R, et al.: Long term results of a randomized study by the Swedish Melanoma Study Group on 2-cm versus 5-cm resection margins for patients with cutaneous melanoma with a tumor thickness of 0.8-2.0 mm. Cancer 89 (7): 1495-501, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Balch CM, Soong SJ, Smith T, et al.: Long-term results of a prospective surgical trial comparing 2 cm vs. 4 cm excision margins for 740 patients with 1-4 mm melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol 8 (2): 101-8, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Balch CM, Urist MM, Karakousis CP, et al.: Efficacy of 2-cm surgical margins for intermediate-thickness melanomas (1 to 4 mm). Results of a multi-institutional randomized surgical trial. Ann Surg 218 (3): 262-7; discussion 267-9, 1993.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Essner R, Conforti A, Kelley MC, et al.: Efficacy of lymphatic mapping, sentinel lymphadenectomy, and selective complete lymph node dissection as a therapeutic procedure for early-stage melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 6 (5): 442-9, 1999 Jul-Aug.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Koops HS, Vaglini M, Suciu S, et al.: Prophylactic isolated limb perfusion for localized, high-risk limb melanoma: results of a multicenter randomized phase III trial. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Malignant Melanoma Cooperative Group Protocol 18832, the World Health Organization Melanoma Program Trial 15, and the North American Perfusion Group Southwest Oncology Group-8593. J Clin Oncol 16 (9): 2906-12, 1998.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Hochwald SN, Coit DG: Role of elective lymph node dissection in melanoma. Semin Surg Oncol 14 (4): 276-82, 1998.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Gershenwald JE, Thompson W, Mansfield PF, et al.: Multi-institutional melanoma lymphatic mapping experience: the prognostic value of sentinel lymph node status in 612 stage I or II melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol 17 (3): 976-83, 1999.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Mraz-Gernhard S, Sagebiel RW, Kashani-Sabet M, et al.: Prediction of sentinel lymph node micrometastasis by histological features in primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Arch Dermatol 134 (8): 983-7, 1998.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al.: Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med 355 (13): 1307-17, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al.: Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med 370 (7): 599-609, 2014.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Stage II Melanoma Treatment

-

Standard Treatment Options for Stage II Melanoma

Standard treatment options for stage II melanoma include the following:

- Excision with or without lymph node management.

Excision

For melanomas with a thickness between 2 mm and 4 mm, surgical margins need to be 2 cm to 3 cm or smaller.

Few data are available to guide treatment in patients with melanomas thicker than 4 mm; however, most guidelines recommend margins of 3 cm whenever anatomically possible.

Depending on the location of the melanoma, most patients can have the excision performed on an outpatient basis.

Evidence (excision):

- The Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial Task 2b compared 2-cm versus 4-cm margins for patients with melanomas that were 1 mm to 4 mm thick.[

1

]

- With a median follow-up of more than 10 years, no significant difference in local recurrence or survival was observed between the two groups.

- The

reduction in margins from 4 cm to 2 cm was associated with the following:

- A statistically significant reduction in the need for skin grafting (from 46% to 11%; P < .001).

- A reduction in the length of the hospital stay.

- A study conducted in the United Kingdom randomly assigned patients with melanomas thicker than 2 mm to undergo excision with either 1-cm or 3-cm margins.[

2

]

- Patients treated with excision with 1-cm margins had higher rates of local regional recurrence (hazard ratio [HR], 1.26; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.00–1.59; P = .05).

- No difference in survival was seen (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.96–1.61; P = .1).

- This study suggests that 1-cm margins may not be adequate for patients with melanomas thicker than 2 mm.

Lymph node management

Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB)

Lymphatic mapping and SLNB have been used to assess the presence of occult metastasis in the regional lymph nodes of patients with stage II disease, potentially identifying individuals who may be spared the morbidity of regional lymph node dissections (LNDs) and individuals who may benefit from adjuvant therapy.[ 3 ][ 4 ][ 5 ][ 6 ][ 7 ]

To ensure accurate identification of the sentinel lymph node, lymphatic mapping and removal of the SLN should precede wide excision of the primary melanoma.

With the use of a vital blue dye and a radiopharmaceutical agent injected at the site of the primary tumor, the first lymph node in the lymphatic basin that drains the lesion can be identified, removed, and examined microscopically. Multiple studies have demonstrated the diagnostic accuracy of SLNB, with false-negative rates of 0% to 2%.[ 3 ][ 8 ][ 9 ][ 10 ][ 11 ][ 12 ] If metastatic melanoma is detected, a complete regional lymphadenectomy can be performed in a second procedure.

Regional lymphadenectomy

No published data on the clinical significance of micrometastatic melanoma in regional lymph nodes are available from prospective trials. Some evidence suggests that for patients with tumors of intermediate thickness and occult metastasis, survival is better among patients who undergo immediate regional lymphadenectomy than it is among those who delay lymphadenectomy until the clinical appearance of nodal metastasis.[ 13 ] This finding should be viewed with caution because it arose from a post hoc subset analysis of data from a randomized trial.

Evidence (regional lymphadenectomy):

- The International Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-1 [JWCI-MORD-MSLT-1193]) included 1,269 patients with intermediate-thickness (defined as 1.2 mm–3.5 mm in this study) primary melanomas.[

14

][Level of evidence: 1iiB]

- There was no melanoma-specific survival advantage (primary endpoint) for patients randomly assigned to undergo wide excision plus SLNB, followed by immediate complete lymphadenectomy for node positivity versus nodal observation and delayed lymphadenectomy for subsequent nodal recurrence at a median of 59.8 months.

- This trial was not designed to detect a difference in the impact of lymphadenectomy in patients with microscopic lymph node involvement.

- Three other prospective randomized trials have failed to show a survival benefit for prophylactic regional LNDs.[ 15 ][ 16 ][ 17 ]

Treatment Options Under Clinical Evaluation for Stage II Melanoma

Postsurgical systemic adjuvant treatment has not been adequately studied in patients with stage II disease; therefore, clinical trials are an important therapeutic option for patients at high risk of relapse.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

参考文献- Balch CM, Urist MM, Karakousis CP, et al.: Efficacy of 2-cm surgical margins for intermediate-thickness melanomas (1 to 4 mm). Results of a multi-institutional randomized surgical trial. Ann Surg 218 (3): 262-7; discussion 267-9, 1993.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Thomas JM, Newton-Bishop J, A'Hern R, et al.: Excision margins in high-risk malignant melanoma. N Engl J Med 350 (8): 757-66, 2004.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Gershenwald JE, Thompson W, Mansfield PF, et al.: Multi-institutional melanoma lymphatic mapping experience: the prognostic value of sentinel lymph node status in 612 stage I or II melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol 17 (3): 976-83, 1999.[PUBMED Abstract]

- McMasters KM, Reintgen DS, Ross MI, et al.: Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: controversy despite widespread agreement. J Clin Oncol 19 (11): 2851-5, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cherpelis BS, Haddad F, Messina J, et al.: Sentinel lymph node micrometastasis and other histologic factors that predict outcome in patients with thicker melanomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 44 (5): 762-6, 2001.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Essner R: The role of lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel node mapping in assessing patient risk in melanoma. Semin Oncol 24 (1 Suppl 4): S8-10, 1997.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Chan AD, Morton DL: Sentinel node detection in malignant melanoma. Recent Results Cancer Res 157: 161-77, 2000.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JH, et al.: Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg 127 (4): 392-9, 1992.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Reintgen D, Cruse CW, Wells K, et al.: The orderly progression of melanoma nodal metastases. Ann Surg 220 (6): 759-67, 1994.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Thompson JF, McCarthy WH, Bosch CM, et al.: Sentinel lymph node status as an indicator of the presence of metastatic melanoma in regional lymph nodes. Melanoma Res 5 (4): 255-60, 1995.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Uren RF, Howman-Giles R, Thompson JF, et al.: Lymphoscintigraphy to identify sentinel lymph nodes in patients with melanoma. Melanoma Res 4 (6): 395-9, 1994.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Bostick P, Essner R, Glass E, et al.: Comparison of blue dye and probe-assisted intraoperative lymphatic mapping in melanoma to identify sentinel nodes in 100 lymphatic basins. Arch Surg 134 (1): 43-9, 1999.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Cascinelli N, Morabito A, Santinami M, et al.: Immediate or delayed dissection of regional nodes in patients with melanoma of the trunk: a randomised trial. WHO Melanoma Programme. Lancet 351 (9105): 793-6, 1998.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al.: Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med 355 (13): 1307-17, 2006.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Veronesi U, Adamus J, Bandiera DC, et al.: Delayed regional lymph node dissection in stage I melanoma of the skin of the lower extremities. Cancer 49 (11): 2420-30, 1982.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Sim FH, Taylor WF, Ivins JC, et al.: A prospective randomized study of the efficacy of routine elective lymphadenectomy in management of malignant melanoma. Preliminary results. Cancer 41 (3): 948-56, 1978.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Balch CM, Soong SJ, Bartolucci AA, et al.: Efficacy of an elective regional lymph node dissection of 1 to 4 mm thick melanomas for patients 60 years of age and younger. Ann Surg 224 (3): 255-63; discussion 263-6, 1996.[PUBMED Abstract]

- Resectable Stage III Melanoma Treatment

-

Standard Treatment Options for Resectable Stage III Melanoma

Standard treatment options for resectable stage III melanoma include the following:

- Excision with or without lymph node management.

- Adjuvant therapy.

Excision

The primary tumor may be treated with wide local excision with 1-cm to 3-cm margins, depending on tumor thickness and location.[ 1 ][ 2 ][ 3 ][ 4 ][ 5 ][ 6 ][ 7 ] Skin grafting may be necessary to close the resulting defect.

Lymph node management

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB)

Lymphatic mapping and SLNB can be considered to assess the presence of occult metastases in the regional lymph nodes of patients with primary tumors larger than 1 mm to 4 mm, potentially identifying individuals who may be spared the morbidity of regional lymph node dissections and individuals who may benefit from adjuvant therapy.[ 3 ][ 8 ][ 9 ][ 10 ][ 11 ][ 12 ]

To ensure accurate identification of the sentinel lymph node (SLN), lymphatic mapping and removal of the SLN should precede wide excision of the primary melanoma.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the diagnostic accuracy of SLNB, with false-negative rates of 0% to 2%.[ 8 ][ 12 ][ 13 ][ 14 ][ 15 ][ 16 ][ 17 ] If metastatic melanoma is detected, a complete regional lymphadenectomy can be performed in a second procedure.

Complete lymph node dissection (CLND)

Patients can be considered for CLND if the sentinel node(s) is microscopically or macroscopically positive for regional control or considered for entry into the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial II (NCT00297895) to determine whether CLND affects survival. SLNB should be performed prior to wide excision of the primary melanoma to ensure accurate lymphatic mapping.

Adjuvant Therapy

Adjuvant therapeutic options for patients at high risk of recurrence after complete resection are expanding, with data still emerging on optimal therapy. Ipilimumab was the first checkpoint inhibitor to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as adjuvant therapy, and has demonstrated improved overall survival (OS) at 10 mg/kg (ipi10) compared with placebo (EORTC 18071 [NCT00636168]).[ 18 ] However, ipi10 has significant toxicity at this dose. The North American Intergroup Trial E1609 (NCT01274338) compared ipi10 and ipilimumab at a lower dose of 3 mg/kg (ipi3) (approved for metastatic disease) with high-dose interferon (HDI). Ipi3 showed a significant improvement in OS whereas ipi10 did not.[ 19 ] These data remove support for HDI as adjuvant treatment for melanoma. As newer checkpoint inhibitors emerge, the role of ipi3 remains to be defined.

Large randomized trials with the newer checkpoint inhibitors (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) and with combination signal transduction inhibitors (dabrafenib plus trametinib) demonstrate a clinically significant impact on relapse-free survival (RFS) with less toxicity than with ipilimumab. CheckMate 238 (NCT02388906) compared nivolumab with ipi10 and nivolumab was superior in RFS and the safety profile.[ 20 ] Data on OS are maturing for all of these trials.

The benefit of immunotherapy with ipilimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab has been seen regardless of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression or BRAF mutations. Combination signal transduction inhibitor therapy is an additional option for patients with BRAF mutations.

Participation in clinical trials to identify treatments that will further extend RFS and OS with less toxicity and shorter treatment schedules is an important option for all patients.

Immunotherapy

Checkpoint inhibitors

Nivolumab

Evidence (nivolumab):

- In a multinational, randomized, double-blind trial (CheckMate 238 [NCT02388906]), patients with stage IIIB, IIIC, or IV melanoma who underwent complete resection were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive nivolumab or ipilimumab.[

20

][Level of evidence: 1iDii] The primary endpoint was RFS and was defined as time from randomization until the date of the first recurrence, new primary melanoma, or death from any cause. Patients who were excluded included those with resection occurring more than 12 weeks before randomization, autoimmune disease, use of systemic glucocorticoids, previous systemic therapy for melanoma, and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status (PS) score higher than 1. Nivolumab was administered at the dose of 3 mg/kg intravenously (IV) every 2 weeks and ipilimumab was administered at the dose of 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for four doses, then every 3 months for up to 1 year or

until disease recurrence, along with corresponding placebo.

A total of 906 patients were randomly assigned: 453 patients to nivolumab and 453 patients to ipilimumab. Baseline characteristics were balanced. Approximately 81% of patients had stage III disease, 32% had ulcerated primary melanoma, 48% had macroscopic lymph node involvement, 62% had less than a 5% PD-L1 expression, and 42% harbored BRAF mutations.

- The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Independent Data Monitoring Committee stopped the study at the protocol-specified interim analysis, when all patients had a minimum follow-up of 18 months, at which time there were 360 events of recurrence-free survival. The median RFS has not been reached in either treatment group. At 12 months, the rate of RFS for patients treated with nivolumab was 70.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 66.1–74.0) versus 60.8% (95% CI, 56.0–65.2) in patients treated with ipilimumab. There were 154 (34%) recurrences or deaths in 453 patients treated with nivolumab versus 206 (45.5%) recurrences or deaths in 453 patients treated with ipilimumab (hazard ratio [HR] recurrence or death, 0.65; 97.56% CI, 0.51–0.83; P < .001). Subgroup analyses of RFS favored nivolumab regardless of PD-L1 expression or BRAF V600 mutation.

- Patients treated with nivolumab had fewer adverse events (AEs), including grade 3 to 4 serious AEs and death. Nivolumab was discontinued in 9.7% of patients, and ipilimumab was discontinued in 42.6% of patients because of AEs. Two treatment-related deaths occurred with ipilimumab (e.g., marrow aplasia and colitis) and none in the nivolumab-treated patients. The AE profile was like the type of checkpoint inhibitor toxicities seen in the metastatic setting, with immune-related events most commonly seen in the gastrointestinal system, hepatic system, and skin. Grade 3 or 4 AEs occurred in 14% of patients treated with nivolumab and in 46% of patients treated with ipilimumab.

Pembrolizumab

Evidence (pembrolizumab):

- In a multinational, randomized, double-blind trial (MK-3475-054/KEYNOTE-054 [NCT02362594]), patients with completely resected stage IIIA, IIIB, or IIIC melanoma were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive pembrolizumab or placebo.[

21

][Level of evidence: 1iDii] The primary endpoint was RFS, defined as time from randomization until the date of first recurrence or death from any cause. If recurrence was documented, patients could cross over or repeat treatment with pembrolizumab. Pembrolizumab was given as an IV infusion of 200 mg every 3 weeks, for a total of 18 doses (approximately 1 year).

A total of 1,019 patients were randomly assigned: 514 to pembrolizumab and 505 to placebo. Baseline characteristics were balanced. Approximately 40% had ulcerated primary melanoma, 66% had macroscopic lymph node involvement, 84% had positive PD-L1 expression (melanoma score >2 by 22C3 antibody assay), and 44% harbored BRAF mutations.

- The EORTC Independent Data Monitoring Committee reviewed the unblinded results at an amended interim analysis when 351 events (recurrences or deaths) had occurred. The results were positive, and the interim analysis of RFS became the final analysis. Patients will continue to be monitored for OS and other secondary efficacy endpoints.

- At a median follow up of 15 months, the 12-month rate of RFS was 75.4% (95% CI, 71.3–78.9) in the pembrolizumab group vs. 61.0% (95% CI, 56.5–65.1) in the placebo group. Pembrolizumab maintained its effect regardless of PD-L1 positive or negative expression or BRAF mutation status.

- Approximately 14% of patients discontinued pembrolizumab due to an AE. Grade 3, 4, or 5 AEs considered to be related to pembrolizumab occurred in 15% of patients. There was one death due to treatment (myositis).

Ipilimumab

Evidence (ipilimumab):

- The open-label, three-arm, North American Intergroup trial E1609 (NCT01274338) compared two doses of ipilimumab with high-dose interferon (HDI) as adjuvant therapy in high-risk patients with melanoma.[

19

] A total of 1,670 patients with resected disease (defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7th edition, as stage IIIB, IIIC, M1a, or M1b) were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to ipilimumab 3 mg/kg (ipi3) or ipilimumab 10 mg/kg (ipi10) every 3 weeks for four doses (induction), followed by the same dose every 12 weeks for four doses (maintenance), or HDI 20 million units/m2 per day, 5 days per week for 4 weeks (induction), followed by 10 million units/m2 daily subcutaneously every other day, 3 days per week for 48 weeks (maintenance).[

19

][Level of evidence: 1iiA].

The trial was designed with two coprimary endpoints, RFS and OS, with a hierarchic analysis to evaluate ipi3 versus HDI followed by ipi10 versus HDI. The time to event was longer than anticipated and the design was amended for a final analysis at a data cutoff date giving a median follow-up time of 57.4 months (range, 0.03 months−86.6 months).

- Ipi3 significantly improved OS compared with HDI (HR, 0.78; 95% repeated CI, 0.61−0.99; P = .044), but not RFS (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.66−1.09; P = .065).

- Ipi10 did not significantly improve OS or RFS compared with HDI (HR, 0.88; 95.6% CI, 0.69−1.12 and exploratory HR, 0.84; 99.4% CI, 0.65−1.09, respectively).

- Salvage treatments were used in 69.7% of patients after ipi3, 51.6% of patients after ipi10, and 86.2% of patients after HDI.

Toxicity with ipi3 was lower than with ipi10; however, both had treatment-related discontinuations and death.

- Treatment-related discontinuations were 34.9% in the ipi3 group and 54.1% in the ipi10 group.

- There were three possibly treatment-related deaths in the ipi3 group, five in the ipi10 group, and two in the HDI group.

The study concluded that evidence no longer supports a role for HDI as adjuvant therapy for patients with high-risk melanoma. Further, ipi3 provides OS data superior to ipi10 compared with HDI. The role of ipilimumab as adjuvant monotherapy is unclear because CheckMate 238 demonstrated that nivolumab was superior to ipi10 in improving RFS, with OS data still maturing.

- In a multinational, randomized, double-blind trial (EORTC 18071 [NCT00636168]), patients with stage III melanoma, who had complete resection, were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive ipilimumab or placebo.[

22

][Level of evidence: 1iiDii] Patients with lymph node metastasis larger than 1 mm, in-transit metastasis, resection occurring more than 12 weeks before randomization, autoimmune disease, previous or concurrent immunosuppressive therapy, previous systemic therapy for melanoma, and an ECOG PS score of greater than 1 were excluded. The ipilimumab dose was 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for four doses, then every 3 months for up to 3 years. The primary endpoint was RFS, defined as recurrence or death (regardless of cause), whichever came first, as assessed by an independent review committee.

- A total of 951 patients were enrolled (475 patients to the ipilimumab arm and 476 patients to the placebo arm). The median age was 51 years, and 94% of the patients had a PS of 0.

- At a median follow-up of 2.7 years, there were 528 RFS events: 234 in the ipilimumab group (49%; 220 recurrences, 14 deaths) and 294 in the placebo group (62%; 289 recurrences, 5 deaths). Median RFS was 26 months for the ipilimumab group (95% CI, 19–39) versus 17 months for the placebo group (95% CI, 13–22). The HR was 0.75 (95% CI, 0.64–0.90); P < .002. The effect of ipilimumab was consistent across subgroups.

- Ipilimumab was discontinued for AEs in 52% of the patients. Patients received ipilimumab for a median of four doses; 36% of patients in the ipilimumab group stayed on treatment for more than 6 months, and 26% stayed on treatment for more than 1 year. Five patients died from drug-related events: three secondary to colitis, one with myocarditis, and one of multiorgan failure with Guillain-Barré syndrome. The most common AEs were gastrointestinal, hepatic, and endocrine in nature and included rash, fatigue, and headache.

An updated analysis was performed at a median follow-up of 5.3 years.[ ]

- The 5-year rate of RFS was 40.8% in patients treated with ipilimumab and 30.3% in patients who received the placebo (HR recurrence or death, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.64–0.89; P < .001) and the median RFS was 27.6% in patients treated with ipilimumab and 17.1% in patients who received the placebo.

- The rate of OS, a secondary endpoint, at 5 years was 65.4% in patients treated with ipilimumab versus 54.4% in patients who received the placebo (HRdeath, 0.72; 95.1% CI, 0.58–0.88; P = .001).

Data from this trial (EORTC 18071), which tested high-dose ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg compared with placebo, served as the basis for the approval of ipilimumab in the adjuvant setting. However, the subsequent intergroup trial, E1609 (described above), demonstrated better outcomes with low-dose (3 mg/kg) ipilimumab, which is also the dose approved for metastatic disease.

Interferon alpha-2b

Evidence (high-dose interferon alpha):

- A multicenter, randomized, controlled study (EST-1690) compared a high-dose interferon alpha regimen with either a low-dose regimen of interferon alpha-2b (3 mU/m2 of body surface qd given subcutaneously three times per week for 104 weeks) or observation. The stage entry criteria for this trial included patients with stage II and III melanoma. This three-arm trial enrolled 642 patients.[

14

][Level of evidence: 1iiA]

- At a median follow-up of 52 months, a statistically significant RFS advantage was shown for all patients who received high-dose interferon (including the clinical stage II patients) when compared with the observation group (P = .03).

- No statistically significant RFS advantage was seen for patients who received low-dose interferon when compared with the observation group.

- The 5-year estimated RFS rate was 44% for the high-dose interferon group, 40% for the low-dose interferon group, and 35% for the observation group.

- Neither high-dose nor low-dose interferon yielded an OS benefit when compared with observation (HR, 1.0; P = .995).

- Pooled analyses (EST-1684 and EST-1690) of the high-dose arms versus the observation arms suggest that treatment confers a significant RFS advantage but not a significant benefit for survival.

- A randomized, multicenter, national trial ECOG-1697 [NCT00003641] evaluated high-dose IV interferon for a short duration (1 month) versus observation in patients with node-negative melanoma at least 2 mm thick or with any thickness and positive sentinel nodes. This trial was closed at interim analysis because of the lack of benefit from treatment with interferon.

- In 2011, pegylated interferon alpha-2b, which is characterized by a longer half-life and can be administered subcutaneously, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the adjuvant treatment of melanoma with microscopic or gross nodal involvement within 84 days of complete surgical resection, including complete lymphadenectomy.

Approval of pegylated interferon alpha-2b was based on EORTC-18991 (NCT00006249), which randomly assigned 1,256 patients with resected stage III melanoma to observation or weekly subcutaneous pegylated interferon alpha-2b for up to 5 years.[ 15 ][Level of evidence: 1iiDii]

- RFS, as determined by an independent review committee, was improved for patients receiving interferon (34.8 months vs. 25.5 months in the observation arm; HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.71–0.96; P = .011).

- No difference in median OS between the arms was observed (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.82–1.16).

- One-third of the patients receiving pegylated interferon discontinued treatment because of toxicity.

Combination signal transduction inhibitors

Dabrafenib plus trametinib

Evidence (dabrafenib plus trametinib):

- In a multinational, randomized, double-blind trial (COMBI-AD [NCT01682083]), patients with stage IIIA, IIIB, or IIIC melanoma with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations who underwent completion lymphadenectomy were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive dabrafenib plus trametinib or two matched placebo tablets.[

23